January 28, 2022

Earlier this month, the RAND Corporation released a report, “Competition and Governance in African Security Sectors: Integrating U.S. Strategic Objectives,” by Stephen Watts, Alexander Noyes, and Gabrielle Tarini, which examines the potential for improving U.S. security sector assistance (SSA) programs to its African partners—specifically in terms of improving U.S. institutional capacity building programs for partner security sectors. Institutional capacity building programs are those, “security cooperation activities that directly support U.S. ally and partner nation efforts to improve security sector governance and core management competencies necessary to effectively and responsibly achieve shared security objectives.” These programs, which are overseen by the Department of Defense’s (DoD’s) Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA), can range from improving the human resources management of partner defense departments to assisting partner militaries in strategic planning. These capacity-building programs are essential, as U.S. train-advise-assist missions are frequently insufficient to ensure partners possess the broader competencies needed to successfully improve their security sectors, and too often result in abuse of civilians by partner military forces.

The term “institutional capacity building” first appeared in the National Defense Authorization Act of 2017, where Title 10 (Chapter 16) § 333 B(4) notes that the Secretary of Defense shall, prior to the initiation of partner capacity building programs, begin “a program of institutional capacity building with appropriate institutions…The purpose of the program of institutional capacity building shall be to enhance the capacity of such foreign country to exercise responsible civilian control of the national security forces of such foreign country.” In essence, institutional capacity building is designed so that it protects against some of the potential downsides of supporting partner militaries in fragile states.

As Watts, Noyes, and Tarini note in their report, well-executed institutional capacity building (ICB) is important, as not only does it give the U.S. a degree of leverage over its partners, it provides a good of high value to leaders in conflict-affected states; through its focus on higher-level pattern interaction, it gives U.S. ICB implementers better relationships with senior decision makers; and it helps partners create security institutions that are resilient to both internal stressors and external competition. However, at the same time, it is important that U.S. ICB programs avoid undermining overarching U.S. goals in the country and region, as ICB programs may require painful sacrifices—such as dismantling patronage networks or developing meritocratic recruitment and promotion methods—that cause partner governments to turn towards alternative security assistance providers, such as China and Russia.

In order to avoid these pitfalls, the RAND authors argue, the U.S. needs to do a number of things to better situate ICB programs into overall American security sector assistance to partner nations. Their first suggestion is that the U.S. needs to formulate a common understanding of effective institutional capacity building across all U.S. agencies and departments in order to create a consensus on what ICB is and what it should be used for. The second is that the U.S. should create a board/council which can act as a clearinghouse for all ICB programs, integrating them into broader security sector assistance strategies. A third is that the U.S. creates ways to incentive partner commitment through programs similar to the Millennium Challenge Corporation. Fourth, that the U.S. needs to have a longer horizon in mind when conducting ICB and SSA, so that American interlocutors on the ground have a better understanding of the specific local dynamics involved. Finally, the authors argue that the U.S. needs to improve efforts at assessment, monitoring, and evaluation (AM&E) of institutional capacity building and security sector assistance programs in order to better understand the reasons why specific programs succeed or fail.

However, before looking at how the authors arrived at these suggestions, it is first important to examine why the authors chose to look at U.S. SSA in Africa. Further, it is important to see how a U.S. failure to properly design institutional capacity building programs in Africa leaves the door open for China to step in and increase its level of influence.

While the U.S. is still the preferred development model for many African countries, China has steadily climbed the ranks, and in at least three countries (Mali, Burkina Faso, and Botswana), has overtaken the American model. Furthermore, China has become a major arms supplier for sub-Saharan African countries, with twenty-one sub-Saharan states receiving major arms from China between 2016-2020. In addition, China accounted for 20% of all arms imports into sub-Saharan Africa, compared to just 5.4% from the United States. Finally, the RAND authors note that China operates over thirty military academies which offer training to foreign military personnel, supporting annual training to approximately 2,000 African military officers across forty African countries. The damage that would be done to the United States influence in Africa, if its ICB and SSA programs were to fail, risks jeopardizing relationships with countries that are already being enticed by China, whether through soft-power military exchanges or infrastructure projects as part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

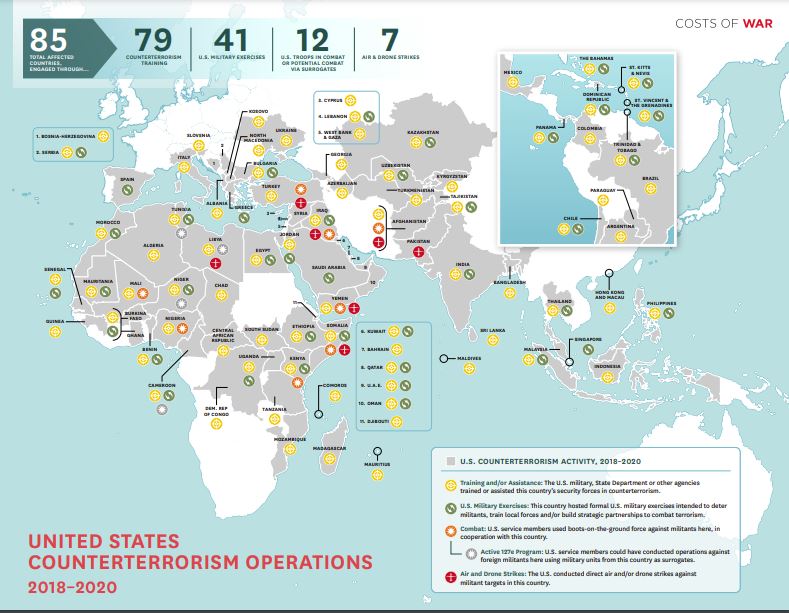

What is clear is that the U.S., over the last twenty years, has focused its security policy in Africa on using a “by, with, and through” approach that aimed to not only combat terrorism and violent extremist organizations (VEOs) in Africa, but to reduce regional instability, which can be an underlying cause of extremism in the first place. The idea underlying such a strategy is to empower allies to solve their own security issues—with American support—in the hope that increasing partner ownership of the problem will help create more accountable security structures in partner nations. The authors note that in recent years, between 13-25% of all U.S. institutional capacity building programs take place in the AFRICOM area of responsibility, focusing on strategic planning; human resources management; logistics; procurement and acquisitions; and the rule of law and human rights.

Linking ICB and Influence

Watts, Noyes, and Tarini then proceed to examine the linkages between U.S. ICB programs and American influence in African countries. They note that the three primary routes for ICB to enhance U.S. influence are by providing a resource of value; by improving partner resilience; and by building relationships built on trust and shared values. In terms of providing partner countries with valuable resources, the authors note that the U.S. uses its capacity building and security sector assistance in order to provide something of value to partners in order to receive something in exchange—for example: basing rights. Though such a direct swap is a more extreme example of providing a resource in exchange for a consideration the U.S. desires, the report also argues that there is reason to believe that ICB programs increase long-term U.S. influence, yielding eventual dividends even when rewards are not seen immediately. For instance, the authors point to the U.S.’ position as number one in the African ranking of best development models, meaning that successful ICB programs—which support peace and justice in post-conflict states—can similarly position the U.S. as the partner of choice in those countries, as it will have delivered a valued commodity and established itself as the model to emulate in Africa.

When it comes to improving partner resilience the report states that, as a resilient security sector is one that prioritizes the interests of the populace over its own narrow interests, a U.S. strategy that promotes resilience in partner military establishments would yield partner militaries that better serve the interests of the populations that they are meant to protect. However, the authors are careful to note the risks involved with institutional capacity building programs, as such programs can run the risk of increasing the chances of a coup if military training is not coupled with effective civilian oversight.

Finally, when it comes to relationship-building, the authors argue that while it is hard to determine the extent to which interactions between U.S. personnel and partner personnel help build relationships built on trust, studies have shown that countries with a high number of military officers educated by the United States typically possessed patterns of voting at the United Nations that were more closely aligned with U.S. policy than those without. However, the authors do note that while such relationships are a valuable starting off point, if the military does not already play a role in the country’s foreign policy decision making, then efforts to build such relationships may yield few gains to the overall U.S. competition in the region, as its military interlocutors will not be in a position to effect matters too greatly.

The report then proceeds to examine U.S. institutional capacity building programs in Niger, Nigeria, Kenya, and South Sudan, examining how they succeeded or failed, and what impact it should have on the design and implementation of such programs in the future.

Case Studies – ICB in Niger, Nigeria, Kenya, and South Sudan

Niger

Niger, which has been a participant in the U.S.’ interagency Security Governance Initiative since 2015, is one of the top regional recipients of U.S. counterterrorism training and equipment. In Niger, U.S. ICB teams work with the Nigerien Ministries of Defense and Interior on functions ranging from strategy to human resources management and budgets, having made particular progress on efforts to redesign force structure, capability-based scenario planning, and standing up inter-ministerial structures between the Ministries of Interior and Defense.

However, the RAND report notes that such institution building would be more easily accomplished if: local coordinators were on hand to cultivate good working relationships and ensure momentum in between visits by U.S.-based team; that shared commitments are written down; that institutional-level efforts are fused with efforts at both the operational and tactical levels; and that the police and military units are both engaged by U.S. teams at the same time.

Local coordinators would help increase American influence, as they would have a better understanding of the problems and potential opportunities better than Washington-based analysts. Furthermore, codifying shared commitments would give the U.S. ICB team leverage to exert influence over partners when particular goals are not being met. Additionally, linking institutional-level efforts with those at the operational and tactical level is important, since, as the authors note, too little attention has been paid to capacity building at the higher level of defense establishments. This results in partner forces that are competent at the tactical level, but incompetently led at the strategic level, leading to inefficiency, waste, and poor leadership that only exacerbates any underlying instability. As current USAID administrator, then-U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, Samantha Power said in a 2014 speech at the United Nations Security Council, “Too often, approaches to SSR are limited to base training or the building up of individual security units and fail to create security institutions that can effectively manage national forces and be responsive to the complex needs of societies…”

Finally, the authors argue that engaging national police forces simultaneously with the military is vital, as African nations, “commonly enable defense and security forces to share missions and operate together…often out of the necessity of scarce resources,” but that, “it also reflects the nature of the threats in play—transnational nonstate actors as opposed to the traditional threat posed by neighboring militaries.” Therefore, by engaging both the military and the police simultaneously, the U.S. ICB teams are better able to support both in their more natural roles, allowing each to focus on their particular competencies, preventing duplication of effort.

Overall, while U.S. institutional capacity building programs have done little to influence the U.S. China rivalry in any meaningful way in the region, interview evidence reviewed by the authors does suggest that these programs have contributed to the U.S. remaining the preferred security provider in the region. Further, they point to a survey of 742 African security sector professionals from the region which found that 27% of respondents preferred the U.S. as training partner, 21% prefer the African Union, 15% prefer the UN, and 9% choosing the EU, with China not even registering. Ultimately, while there is evidence that foreign security sector assistance has not made Nigeriens that much safer, the authors argue that American experience in Niger demonstrates the importance of maintaining successful partnerships with regional countries.

Nigeria

The report then proceeds to an analysis of U.S. institutional capacity building efforts in Nigeria, which has seen much more limited progress than in Niger. While it has received a good deal of U.S. support, the country is still beset by security problems, with Boko Haram and ISWAP operating in the northeast part of the country, conducting attacks on both civilian and military targets. U.S. security sector cooperation with Nigeria, covers the $7.1 million in International Military Education and Training (IMET) funding from 2016-2020 along with $1.1 million as part of the African Military Education Program benefitting Nigerian military schools. In addition, the country has also received $1.3 million in Foreign Military Financing (FMF) to support maritime security, military professionalization, and counterterrorism (CT). Further, as part of the Trans-Sahara Counterterrorism Partnership (TSCTP), Nigeria has received $9.3 million worth of training, equipment, and advisory support for CT efforts. Finally, the country has $590 million in government-to-government sales under the Foreign Military Sales system, including up to 12 A-29 Super Tucano turboprop light attack aircraft worth $497 million for countering illicit trafficking in Nigeria and the Gulf of Guinea.

However, despite this level of assistance, the report’s authors note that evidence suggests that Nigeria views American ICB programs as intrusive, creating risks for espionage, but also limiting opportunities for graft and corruption. The RAND authors also do not find that the security relationship has made much progress on inculcating American values, with the Nigerian military having been credibly accused of committing war crimes only about eighteen months ago. While concerns about such behavior had forced the Obama administration to cancel the delivery of American-made helicopters in 2014 and then freeze delivery of the A-29s in early 2017, the Trump administration made the decision to go ahead with the sale, with the fighters being inducted into the Nigerian Air Force in August of 2021.

In sum, the authors feel that gains from U.S. ICB assistance to Nigeria is limited across the resources, relationships, and resilience pathways. While these limited gains have not affected the U.S.-China competition—as China’s interest in Nigeria appears to be predominantly economic in nature—the RAND authors argue that it is still unavoidable that, despite best intentions, the U.S. has made extremely little impact in transforming the defense institutions in Nigeria.

Kenya

As a major contributor to the African Union’s Mission to Somalia (AMISOM), Kenya is a vital U.S. partner in the fight against al-Shabaab. Furthermore, the country has a long history of close relations with the U.S. and its military is one of the most capable in Africa, having received over $560 million in security assistance in 2020 alone. With that assistance, the RAND report notes, the Kenyan security sector has made progress, making strides in enterprise resource planning, inventory management, and logistics management.

However, the report notes that, as with other American ICB programs, the U.S. faces a problem with follow-through from partners when American staff are not in the country. That said, the report does note that the relationship between U.S. officials and Kenyans is one of mutual respect and shared interest, which should help differentiate the relationship from the one with China, which, despite recent entreaties from the Chinese Foreign Ministry, has had some difficulties.

Overall, the report’s authors argue that despite some mixed results, U.S. ICB initiatives have contributed to some gains in the bilateral relationship, though frequently, these gains are due to direct U.S. financial and equipment support to partner militaries.

South Sudan

If Niger, Nigeria, and Kenya demonstrated the U.S.’ ability to achieve at least a measure of success through its ICB programs, South Sudan is the chief counter-example. The country, which has been wracked by violence and conflict since a civil war broke out in 2013, has received enormous amounts of U.S. security sector assistance, despite human rights abuses such as the Sudan People’s Liberation Army’s (SPLAs) use of child soldiers. The RAND report argues that the U.S.’ ICB programs in South Sudan were widely considered failures, as there was a persistent lack of buy-in from the South Sudanese military, demonstrated by a lack of resources invested in force sustainment; in a lack of coherence within the budget and immature public financial management; and entrenched antagonism to civilian control of the military.

Watts, Noyes, and Tarini argue that the U.S.’ failure in South Sudan was because its strategy was built on a poor foundation of only working with the SPLA, rather than creating an enabling political environment. Interviews conducted by the authors found that because members of the military were loyal to individual leaders rather than the state as w whole, U.S. assistance exacerbated the fragmentation between the military and the civilian leadership, massively hindering the implementation of reforms.

Overall, the authors argue that not only did U.S. ICB programs fail to improve the resiliency of the SPLA, American badgering of its South Sudanese counterparts about its human rights abuses created opportunities for China to expand its influence there. Therefore, U.S. efforts in South Sudan were largely a failure as they failed to provide South Sudan with a resource that they valued highly; failed to improve the SPLA’s resilience; and there appeared to be few shared values on which to build a meaningful relationship. All of which limited the ability of the U.S. to increase its influence with the government of South Sudan.

RAND Conclusions and Recommendations

The RAND report then closes with a synthesis of the authors’ findings, along with a series of recommendations to help improve U.S. ICB programs so that they are able to act as influence multipliers in partner countries.

One of the first major takeaways from the report is that for U.S. capacity-building efforts to be successful, partner leadership needs to be committed to reforms and value what the U.S. is offering. In Kenya and Niger, partner leadership recognized a need for reform and consequently valued the ICB that the U.S. was offering. In contrast, in Nigeria and South Sudan, military leaders often resented U.S. pressure to conduct reforms, limiting the ability of the U.S. to make real progress.

A second major conclusion reached by the RAND authors is that the U.S. needs to be in it for the long haul when it comes to ICB and SSA. They argue that by working with the same partners on the same issue over a longer period than a typical U.S. embassy tour, it allows for more beneficial working relationships to be established. While the length of a relationship does not necessarily equate to the depth of the relationship, a short-term relationship is unlikely to ever deepen into a full level of trust between both sides.

Relatedly, the authors also argue that an in-country presence is required in order to maintain and deepen relationships. While it may appear to be self-explanatory, an in-country presence is more advantageous than a remote one, as it allows for more consistent progress, as partners can receive real-time updates and collaboration on important, but tricky, capacity-building issues.

Watts, Noyes, and Tarini note that in explaining the success or failure of ICB programs, the most valuable ways to ensure success is to have partners with real commitment to reforms, along with U.S. support that is both long-term, and in-country. In essence, more robust partnerships are required for security assistance programs to yield truly transformational results.

The authors then proceed to offer two overarching recommendations, to go along with five more specific practices U.S. ICB programs should observe when conducting institutional capacity building programs. The first overall recommendation is that the U.S. better prioritize partner resilience, albeit with modest expectations for the degree of transformation achieved. They argue that instead of looking for a complete transformation of a partners’ security sector, the U.S. should instead look for more incremental improvement. However, the authors make clear that where such improvements are not possible, the U.S. needs to be willing to cease security aid if the partner engages in behavior that causes harm to the civilian population.

A second overarching recommendation made by the RAND authors is that the U.S. needs to embed the provision of security resources to partner countries within more comprehensive planning efforts. In essence, the argue that while the Department of Defense has made strides in the assessment, monitoring, and evaluation of their security cooperation programs, there is room for improvement, as the DoD too often uses the Significant Security Cooperation Initiatives process as a way to push predetermined train-and-equip packages rather than as a comprehensive plan for the partner, informed by a country-specific theory of change.

When it comes to more specific recommendations, the authors argue that the U.S. needs to codify and actively socialize a common understanding of what institutional capacity-building truly is across the interest of the U.S. government, as that lack of definition has prevented real alignment between DoD and State on ICB programs and what constitutes success for those programs. A second, related recommendation, is that the U.S. strengthen interagency coordination via the creation of a security sector assistance hub to coordinate programs across State, DoD, the NSC, USAID, the Department of Justice, and the Department of Homeland Security. In essence, there needs to be top-level ownership of ICB programs and their goals, along with an interagency process that incorporates the expertise of all relevant stakeholders into the development of these programs.

The third recommendation the report makes is that the U.S. needs to encourage its partners to commit to reforms through selective, graduated assistance, along the lines of what the U.S. does with the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC). As has been noted elsewhere, such a model makes use of quantifiable indicators of performance to identify partners; requires those partners to lead the design and implementation of projects; and not only screens candidates and programs based on a cost-benefit analysis, but conducts a rigorous evaluation of how and why the program succeeded or failed. In essence, an MCC-style interagency security assistance pilot program could make use of positive conditionality, using milestones and a tier system for partners so that they “unlock” further assistance as they complete reform goals, allowing them to eventually “level-up” into a new status, allowing access to even greater forms of assistance. Such a tier system could even gate lethal assistance such that it is not provided until most top-level governance reforms are completed. However, much of that would depend on the individual country involved and their current security environment.

Relatedly, the authors also argue that the U.S. needs to redouble the assessment, monitoring, and evaluation efforts (AM&E) of its ICB programs. While the 2017 NDAA ushered in a new AM&E program for State’s Title 10 security cooperation programs, the authors argue that obstacles remain, including poor data collection and dissemination, vaguely defined objectives, and resistance to AM&E processes from within the Department. In addition, this is coupled with the fact that ICB programs are notoriously difficult to evaluate. However, the authors assert that State and DoD should redouble their efforts to implement rigorous AM&E for security sector assistance, applying it to its ICB programs through the implementation of reporting and tracking requirements for planners and implementers. As noted in their report, currently, evidence of the efficacy of ICB programs is relegated to after-action reviews of implementers or other anecdotal evidence. A forthcoming RAND study will reportedly show that the DSCA was unable to verify whether a large portion of ICB activities were truly institutional capacity building due to a low level of information available.

Finally, the report argues that, in order to build relationships with partner countries, the U.S. needs to commit to longer tours and more civilian personnel at AFRICOM; commit more resources to programs like the Global Defense Reform Program; make better use of U.S. programs and organizations that emphasize continuity in partner country programs, such as the National Defense University’s Africa Center for Strategic Studies; and coordinating ICB efforts with allies that may have deeper relationships or a greater degree of influence with partner officials.

Concluding Thoughts

Competition and Governance in African Security Sectors raises a number of important issues that will be vital for the United States to address if it wishes to transform its relations with African countries, particularly ones that are conducting the difficult transition from conflict-afflicted to post-conflict states. Furthermore, the situation is complicated by the fact that U.S. security assistance to Africa during the Cold War frequently exacerbated the levels of violence, and ignored deteriorating governance by many African partners during the time period. As another RAND report, “Building Security in Africa: An Evaluation of U.S. Security Sector Assistance in Africa from the Cold War to the Present,” notes, the U.S. not only deemphasized governance issues during its Cold War-era competition with the Soviet Union, its security assistance actually served to increase the incidence of civil wars, as it inflamed intercommunal tensions.

What is abundantly clear, is that the way that the U.S. has conducted its security assistance programs—primarily focusing on building the capacity of partner militaries—has yielded only partially satisfactory results, too often failing in preventable ways. In their 2017 report, “Security Sector Governance in Africa: A Handbook,”, the Geneva Centre for Security Sector Governance comes to some of the same conclusions that the RAND authors do, noting that, some of the many challenges that come with attempting to transform African security sectors are that the partner countries frequently lack a strong tradition of democratic norms; that U.S. interlocutors lack a true understanding of the underlying domestic political context, limiting implementers’ ability to move beyond the defense sector and be truly transformational; and that partners often have differing ideas about the level of importance and involvement of the U.S. over issues of professionalism and ensuring the protection of human rights. These differing perspectives between the U.S. and its African partners leaves them dangerously exposed to Chinese and Russian influence.

Seemingly all major reports and studies in recent years agree that, as currently constructed, U.S. security sector assistance does not yield the gains that U.S. planners are looking for. Too often, U.S. security sector assistance and institutional capacity building is too narrowly focused on tactical capabilities over the administrative capacity and professionalism of these forces. As argued in the RAND report and elsewhere, the U.S. has not received sufficient bang for their security sector assistance buck, and its security assistance has too often enabled democratic backsliding by partner governments or human rights abuses by partner militaries. Therefore, a new approach is needed.

Such a new approach, seemingly everyone agrees, requires a renewed focus on creating more lasting relationships with ICB partners, specifically through the creation of high-level, in-country U.S. coordinator positions which can help facilitate partner buy-in. However, before it can do so, the U.S. first needs a more cohesive conception of what ICB efforts should aim to accomplish at the highest level. A focus on simply improving the tactical abilities of individual partner police and military units is insufficient to realize real changes in partner defense institutions that are needed to truly transform the sector into something that provides value for the population.

Furthermore, if the U.S. wants its institutional capacity building projects to redound to its credit in its global competition with China, then it needs to make sure that ICB programs are leveraged so that they help create better working relationships with partner officials, yielding greater avenues for American influence. In addition, as mentioned in a 2020 Civilians in Conflict report, when designing SSA and ICB programs, it would behoove U.S. decisionmakers to involve civil society, and do so early on in the process, as it would provide meaningful public participation in government decision making, giving the entire process a greater degree of legitimacy in the eyes of the domestic public.

Finally, the U.S. needs to more stringently monitor and evaluate its ongoing programs, with particular emphasis paid on how the particular program is serving overall U.S. goals in the country. For instance, Mali had been experiencing an extended period of democratic backsliding, but despite that, the country still received nearly $79 million in U.S. development assistance in 2020, with only 1% going to democracy, rights, and governance programming. Such continued foreign assistance allowed and encouraged the government to pursue a security strategy that focused more on driving out extremists than protecting the people, leading to an erosion of government legitimacy, and creating the conditions for the recent coups. As Aude Darnal and Evan Cooper of the Atlantic Council noted last summer, too often, U.S. security assistance goes to forces that undermine the rule of law and human rights, and does little to improve stability in those countries. Part of remedying this involves adopting a “Do No Harm” concept for capacity building programs, endeavoring to ensure that U.S. assistance does not result in making conditions inside the partner country worse by providing overmilitarized assistance to defense establishments that are too fragile to receive it.

U.S. security sector assistance and institutional capacity building programs are a vital way for the U.S. to provide an item of value to fragile states that are coming back from years of conflict and strife. However, as currently constituted, American assistance too often does as much harm as good, both to the partner country’s population, and to the American reputation abroad. It is time that U.S. decision makers reevaluate these programs, making sure that when security training and assistance is provided to a partner military, its civilian oversight institutions are being built up to a similar degree. In addition, American ICB programs need to be designed from the top-down, starting with the desired end point for partner security sectors, and then determining all the intervening steps necessary to arrive there. In that way, it is important that programmatic steps are properly sequenced, so that military and police forces abilities do not outpace their Ministries of Defense or Interior’s ability to properly oversee them.

However, even requirements that security cooperation activities have logic frameworks for capacity building is insufficient if those requirements do not mandate that planners and implementers devise frameworks that have clearly quantifiable metrics. For instance, the DoD’s Defense Security Cooperation University’s guidance on, “Whole of Government Security Cooperation Planning,” outlines an example of a logic framework for a theoretical maritime security and Maritime Domain Awareness mission in a hypothetical partner nation. While the framework does a decent job of building the conceptual underpinnings of a project to improve a partners ability to conduct counter-trafficking and counter-piracy missions, it is both lacking in the real specifics that connect the programming with the problem that is attempting to be addressed, and contains vague generalities such as “[Partner Nation] officials demonstrate explicit national will to contribute to regional security and stability operations.” Such ambiguity is exactly how the U.S. gets into trouble with its security assistance programs. Vagueness, while seemingly innocuous, makes it tremendously difficult to evaluate success once a program is undertaken. What is required then, is a greater degree of specificity from a program’s outset, so that clearly defined, measurable goals are either reached or not, providing evaluators in Washington a much clearer picture of the progress of a given project.

Only once the U.S. ensures that partner militaries have robust levels of civilian oversight and the requisite support structures should ICB programs provide increased lethal assistance to partner armed forces. Furthermore, civilian oversight mechanisms are unlikely to appear overnight. Therefore, U.S. policy makers need to understand that in order to facilitate a transformation of partner countries’ security sectors, they need to make clear that the U.S. is committed for the long-term, with dedicated personnel situated in-country on a continuous basis.

It is undoubtedly true that many of the U.S.’ African partners need to improve their security sectors in order to improve service delivery and governance in large swathes of their countries wracked by violent extremists and other conflicts. However, it is clear that American train-advise-assist missions have not been getting the job done. If the U.S. wants to see transformational progress in building partner capabilities, it will need to reevaluate how it conducts its ICB programs, only initiating such programs when partners are committed to making demonstrable changes. U.S. success in transforming partner security sectors, if it helps prevent democratic and human rights backsliding, could pay huge dividends in the growing great power competition with China. If the U.S. comes to be seen as the best model for security assistance, in addition to being the preferred model for development, then it will be much better positioned to ward off challenges from China in the coming great-power competition.

Institutional capacity building is the sine qua non of security sector assistance, and too often, U.S. security assistance is focused too much on a whack-a-mole game of fighting insurgents over creating partners that are able to be positive providers of security in their region. As seen in Uganda, U.S. institutional capacity building has continued despite clear evidence of corruption and human rights abuses, providing its leadership with a sense of impunity. Without first building up the requisite support structures, boosting a partner militaries’ tactical and operational ability is a recipe for disaster. By building up partner competency, without concomitant increases in effective civilian control, the U.S. merely exacerbates the power imbalances that have led to coups in many African countries in just the past few years.

However, U.S. decision makers need to enter discussions about security assistance with clear eyes, and an understanding both of a potential partner’s actual willingness to conduct reforms, and a clear commitment to end programs with partners that do not put in the required level of effort. Cutting off a partner may be difficult, damaging the relationship temporarily and preventing the U.S. from achieving its immediate security objectives. Nevertheless, doing the same thing over and over, expecting different results is the definition of insanity, a waste of taxpayer money, and counterproductive to the aspirations of both the U.S. and partner citizenry. Continuing to work with a partner that fails to initiate reforms or allows its security forces to abuse its population will only damage the U.S.’ reputation in the long term, creating the conditions for future armed extremist groups to form.

If the United States wishes to see better long-term results, rather than pyrrhic counterterrorism victories, it must reevaluate how it conducts security sector assistance and institutional capacity building programs. If it does not, it will not only continue to throw money away, it will risk losing its African partners to Chinese influence.