March 11, 2022

In today’s globally interconnected world, war and strife in one part of the Earth can, and often does, have an enormous impact not only on the immediate region, but the rest of the planet. Indeed, the effects of the war even reach beyond the Earth, as well. While the majority of U.S. coverage of the crisis has focused on its impact on the United States, Russia, or Ukraine, the conflict has had an unavoidable impact on the rest of the world, as sanctions and votes at the United Nations force countries to either take a side or remain conspicuous in their neutrality. As the conflict continues, with no end in sight, it is useful to examine the impact that the first few weeks of the conflict have had on countries around the world, from China and Turkey to Brazil and Kenya.

To that end, the best place to begin would be a March 4 piece from the International Crisis Group, “The Ukraine War: A Global Crisis?” from Amanda Hsiao, Praveen Donthi, Dina Esfandiary, Ali Vaez, Naysan Rafati, Nigar Göksel, Mairav Zonszein, Murithi Mutiga, Piers Pigou, Falko Ernst, Mariano de Alba, and Richard Gowan. The piece aimed to examine the international reaction to the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine through the lens of individual countries’ votes on the UN General Assembly demanding that Russia immediately end its military operations in Ukraine. While only five countries—including Belarus, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Eritrea, Syria, and Russia—voted against the resolution calling for Russia to, “immediately, completely, and unconditionally withdraw all of its military forces from the territory of Ukraine within its internationally recognized borders,” thirty-five more countries abstained from the vote, which demonstrates that there still exists some major divisions between the United States, Europe, and a number of their international partners. Therefore, using the Crisis Group report as a springboard, it is a good idea to look at the truly international impact of the crisis in Ukraine.

Asian Reactions and Implications

The Crisis group authors smartly begin with a look at the United Nations votes of China and India, who both abstained from condemning Russia’s actions, albeit for divergent reasons. While it is rather unsurprising that China abstained at the General Assembly—after already having abstained at the Security Council to allow Russia to veto a draft resolution deploring their invasion of Ukraine—the cover Beijing provides for Moscow remains troubling, and a major barrier to concerted international action on the conflict. The Crisis Group authors note that in its votes at the UN, China desires to live up to its professed “no-limits” friendship with Russia; to maintain its already deteriorating ties with Europe; and to maintain the inviolability of states’ territorial integrity. While noting the invasion’s potential implications for China’s own relationship with Taiwan, the Crisis Group authors argue that, ultimately, the Ukraine crisis does not affect core Chinese interests, and therefore Beijing will likely remain risk-averse and largely above the fray, looking to avoid anything that would further impede the economic relationship with European nations.

To that end, on February 25, Foreign Minister Wang Yi held a phone call with UK Foreign Secretary Liz Truss, EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs Josep Borrell, and French President Emmanuel Macron, outlining China’s position on the Ukraine crisis in five main points. Those points essentially stated that China respects the UN Charter’s requirements on safeguarding states’ sovereignty and territorial integrity; that it advocates a cooperative and sustainable security, though not through the expansion of large alliance networks like NATO; that it believes that all parties to the Ukraine issue need to exercise restraint; that it encourages a diplomatic and peaceful resolution to the crisis; and that China believes the UN Security Council should play a constructive role through the facilitation of a diplomatic solution rather than the use of force or sanctions. While such rhetorical support for a diplomatic solution is somewhat boilerplate language for a country with little to gain in the crisis, the fact that China continues to give Russia moral and political cover—by espousing the notion that Russia’s actions were brought on as a result of NATO expansion—is troubling and demonstrates Beijing’s belief that the West brought this crisis upon itself.

However, while the Crisis Group report notes that China’s top banking regulator has publicly stated that China would not take part in Western financial sanctions, and may even attempt to assist Moscow with an economic helping hand later—despite potential difficulties—there is a strong argument to be made that despite China’s abstentions, the crisis in Ukraine may be doing a good deal to drive a wedge between Beijing and Moscow. As the Center for a New American Security’s (CNAS) Andrea Kendall-Taylor said during a February 23 discussion at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) on, “What’s Next for the China-Russia Relationship?”, while the China partnership may embolden Putin to be aggressive in Ukraine, that very same aggression, somewhat paradoxically, deepens already existing fissures in the relationship.

In the discussion, Kendall-Taylor points out that a major difference between Russia and China is Beijing’s taste for risk and destabilizing actions, which undermine international institutions and international law. As Fareed Zakaria recently noted in an interview with Ezra Klein of the New York Times, China, “benefits enormously from international stability, from international order, even from international institutions…China’s number one principle for the last 20 years, and what it criticizes the U.S. for, is state sovereignty, the inviolability of state sovereignty. Which is why this whole business with Russia invading Ukraine has been so awkward for Beijing.” Therefore, while the West should not look to Beijing to immediately do anything to punish Moscow for its escalation in Ukraine, it should consistently message China that further deepening their relationship with an unpredictable Russia will hinder China’s reputation for prudent international behavior.

In terms of India’s abstention at the UN General Assembly, the Crisis Group authors argue that New Delhi’s decision was motivated by a realist worldview, which resists being caught in between NATO countries and Russia on security issues. Russia and India already possess a strong relationship in the defense sector—with between 60-70% and as much as 85% of Indian defense equipment being procured from Russia—and in December 2021, the two countries announced an expansion of security ties, including the Indian purchase of S-400 missile defense systems, despite the already growing tensions near Ukraine.

As noted by CSIS’ Richard M. Rossow in a March 1 commentary, while, “India has managed to maintain close relations with Russia while dramatically improving strategic ties with the United States…Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has made this position hard to maintain.” Rossow further notes in a March 2 discussion on, “The Ukraine Crisis and Asia: Implications and Responses,” that while, “non-alignment certainly still remains the name of the game in Delhi,” and that, “India avoiding taking a hard line on Russia…[is] not terribly surprising,” India is in a bind, stuck between its commitments to a free, open rules-based international order and a $2 billion a year reliance on spare Russian military equipment.

While, in prior years, the U.S. has been understanding of Indian reliance on Moscow for weapons and equipment—with the Crisis Group authors noting that Russia is a key part of India’s strategy to protect against China in the same way that India is a part of the Western strategy to protect against China—it does not mean that it is immune to criticism, and New Delhi will have to work carefully to avoid angering U.S. lawmakers who could impose CAATSA sanctions on India in light of their S-400 procurement. While such sanctions are unlikely to be imposed on such a key U.S. ally, it does show the extent to which the Ukraine crisis can drive a wedge between even Quad partners. Furthermore, the crisis demonstrates that more needs to be done on the U.S. and EU’s part to wean India off of its dependency on Russian arms as well as to strengthen the EU-India relationship in terms of security.

Another Asian country directly affected by the crisis in Ukraine is Pakistan, which has seen relations with the U.S. deteriorate following the Taliban’s victory in Afghanistan. Prime Minister Imran Khan’s state visit to Moscow during the outset of the invasion on February 24 was highlighted for its awkward timing—and the implication that the Prime Minister’s presence conferred Pakistan’s blessing on Russia’s military adventure—and Khan returned home rather empty handed, with only deals to buy Russian gas and wheat. Furthermore, critics were left skeptical of the agreement in light of Western sanctions. Moreover, while Khan has rejected Western pressure to support the UN General Assembly resolution condemning the Russian aggression, his criticism of the West may be more about shoring up support in the Pakistani Parliament as his opposition moves forward a vote of no-confidence due to the Prime Minister’s poor handling of the economy and poor governance.

That having been said, Pakistan would be wise to consider its rhetoric in light of the economic relationship the country has with the West as well as with Russia. As noted elsewhere, Pakistani exports to the UK, Germany, Netherlands, Spain, Italy, Belgium, France, Canada, Poland, and Portugal—all of which voted for the measure condemning Russia at the UN General Assembly—total around $8 billion per year, while Pakistan’s exports to the U.S. total just under $4 billion per year. Meanwhile, exports to Russia in 2019 were only $277 million, a major difference for a Pakistan that is vitally dependent on its exports for economic growth. As the Crisis Group authors point out, with a trade deficit over $30 billion, Pakistan cannot afford to become further reliant on a Russia under massive international sanctions, as Moscow would be in no position to assist Pakistan. With Khan rumored to have already lost the support of the Pakistani military, he is in a delicate position, and with Pakistan’s abstention at the General Assembly, it all serves to only further Khan’s isolation, further clouding the picture in Islamabad.

The Middle East and Turkey

The Crisis Group report then proceeds to analyze the votes of the countries in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), noting that all of them voted for the resolution condemning Russia, though the United Arab Emirates did abstain from an earlier Security Council vote condemning the invasion. Here, the authors point out that despite improving ties with Russia, GCC countries still have had to balance their reliance on the U.S. security umbrella with a desire to keep relations with Moscow stable. As it is, the UAE, Oman, and Qatar already import huge amounts of wheat from Russia and Ukraine, and while ample grain storage is unlikely to make disruptions from the war a problem in the short-term, it is simply another factor that further complicates the relationship.

Illuminating the push and pull was the UAE’s abstention at the Security Council, which was almost immediately repaid by Moscow, as Russia’s support for an arms embargo on the Houthis in Yemen was seen by some as a quid pro quo for Abu Dhabi’s vote at the UN. Further illustrating the impact of the tug-of-war between the West and Russia was Saudi Arabia, which did vote in favor of condemning Russia’s invasion at the General Assembly, but reiterated its commitment to the OPEC+ production quotas as part of its agreement with Russia. Furthermore, Saudi Arabia has resisted Western entreaties for the region to produce more oil to offset Western sanctions on Russian oil and gas. While a Western diplomat in Riyadh is quoted as saying, “The feedback that we got from the Saudis is that they see the OPEC+ agreement with Russia as a long-term commitment and they are not ready yet to endanger that cooperation … while making it clear that they stand with the West when it comes to security cooperation,” the Crisis Group authors note that the damage to the relationship with the West may have already been done by Gulf States’ reticence to get in line with immediate condemnations of the invasion. Moving forward, while Saudi Arabia and the UAE want the U.S. and Europe to provide them with more weapons for the war in Yemen, GCC countries will have to realize that they will find it increasingly difficult to walk the fine line between the West and Russia on Ukraine.

Like the Gulf Cooperation Council countries, Israel also voted for the resolution, but for largely different reasons. Israel, like GCC countries, maintains relations with both the West and Russia, though the relationship was much closer during Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s time in office—especially when Israel refused to join a vote censuring the 2014 Russian invasion of Crimea and Donbas. In recent days, Prime Minister Naftali Bennet has tried to continue Israel’s delicate balancing act, attempting to mediate with Putin and Russia, with the thanks of Ukrainian President Zelenskyy. However, with Israel concerned that their condemnation of the invasion could lead to Russia increasing its arms sales to Syria or Hezbollah in Lebanon, the authors note that the country will increasingly find it hard to stay on the sidelines, though Israel does have a record of placing national security issues above its concerns about possible antisemitism.

Another major Middle East player is Iran, which abstained on the General Assembly resolution condemning the Russian invasion. While President Raisi echoed Russian talking points— blaming NATO expansion on the crisis, and Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has also said that the “root cause” of the crisis can be laid at the feet of Western powers—Iran cannot be happy about Russian demands regarding the JCPOA and sanctions exemptions possibly sabotaging the deal’s return when it is finally nearing completion. The Crisis Group authors note that if talks break down now, the U.S. and EU might begin to shift towards a more coercive diplomacy, with Iran’s nuclear stockpile emerging as yet another area of dangerous contestation between Russia and the West. While further proliferation of nuclear weapons is not in either the U.S. nor Russia’s interest, Iran’s isolation after President Trump withdrew from JCPOA led to Tehran’s increased reliance on China and Russia for trade. Ultimately, while Russia may strongly dislike nuclear weapons in Iran, it may decide that increased trade, especially in light of increasing Western sanctions, may be worth the long-term risks.

Finally, the authors look at Turkey, which voted in favor of the UN General Assembly resolution, but which also has to walk a fine line in regards to the Ukraine conflict. Turkey’s economy not only relies on large numbers of Russian tourists every year, but Russia has been one of Turkey’s most important trade partners in recent years, with over $30 billion in total trade volume between the two sides in 2021. Furthermore, Turkey has, in recent years, procured Russian missile defense systems, damaging relations with the U.S.

However, over Ukraine, Russia and Turkey have taken different sides, with Ankara supporting Ukraine’s independence and territorial integrity and strongly condemning the Russian seizure of Crimea. While Turkey’s Erdoğan has made repeated attempts to mediate the crisis and attempted to position Turkey as a neutral actor, the country still has condemned the Russian invasion, calling it a war, and implementing the Montreux Convention as to somewhat restrict the passage of warships into the Black Sea. Finally, complicating matters even further is the fact that Ankara must worry about Russian backlash in Syria, where Moscow might punish Turkey by ratcheting up pressure on Idlib, forcing large numbers of refugees into Turkey and then into Europe. Ultimately, the crisis may bring Ankara and NATO closer together, especially as the two sides coordinate on the response to the invasion, as a Russian victory that sees Moscow gaining an even greater hand in the Black Sea may only exacerbate pre-existing Turkish fears of the Black Sea becoming, “a Russian lake.”

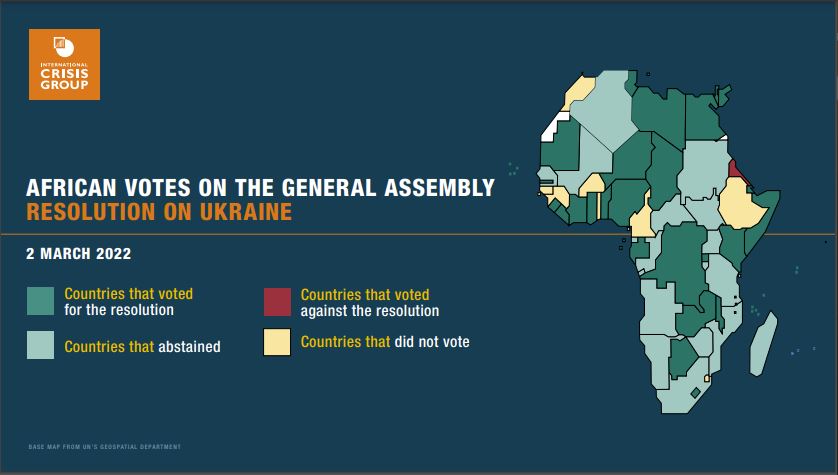

African Reactions to the Russian Aggression

Continued Russian aggression towards Ukraine does not just have a regional impact, but has global reverberations. In Africa, reaction to the Russian actions in Ukraine were mixed, with twenty-eight states supporting the resolution, fifteen abstaining, and Eritrea voting against. While it has been pointed out that the global south has mostly declined to take a side in the current crisis for various reasons, it is important to look at the reasons why this is the case. For instance, the Crisis Group’s report begins its look at Africa through the lens of Kenya, a non-permanent UN Security Council member which did support the UN General Assembly resolution. The country, which has taken a stand against the Russian invasion, argues that Ukraine’s situation echoes its own past, when Africa’s borders were not drawn in Nairobi or Addis Ababa but imperial capitals in London and Paris.

Ultimately, the country feels that it has to take a stand for the territorial integrity of smaller countries that are often at the mercy of their larger, more powerful neighbors. As Kenya’s Ambassador to the UN, Martin Kimani stated in a February 22 speech to the Security Council, “Kenya registers its strong concern and opposition to the recognition of Donetsk and Luhansk as independent states. We further strongly condemn the trend in the last few decades of powerful states, including members of this Security Council, breaching international law with little regard. Multilateralism lies on its deathbed tonight. It has been assaulted today as it has been by other powerful states in the past.” However, as Kimani’s statement makes clear, it is not just Russia that Kenya views as an imperialist nation with little regard for smaller countries rights and sovereignty, but the U.S. as well. Moreover, Western sanctions on Russia are likely to further restrict already burgeoning trade between Russia and Kenya, further complicating Kenya’s decision. To that end, the Crisis Group authors note that while Nairobi has called out the Russian aggression in this case, it is likely that in the future, the country will strive to occupy more of a middle ground, calling for an end to the invasion, but refraining from supporting the use of sanctions, frustrating U.S. and European interlocutors.

Acting in a more ambivalent manner than Kenya was South Africa, which abstained from the UN resolution condemning Russia. South African President Cyril Ramaphosa defended his country’s decision, arguing that the proposed resolution did not do enough to call for meaningful engagement between Ukraine and Russia on a peaceful resolution of the issue. While Praetoria did eventually call on Russia to withdraw its troops from Ukraine, it also has to walk a fine line with Russia, with which it has a long history of economic and military cooperation. Ultimately, the Crisis Group authors argue that Praetoria will likely take its cue from the rest of the continent as well as the G7 and China, with an approach that ultimately urges a diplomatic resolution of the crisis.

As mentioned above, though just over half of African nations backed the UN resolution condemning Russian aggression, many of their governments have acted cautiously towards Moscow. The Crisis Group report notes that not only does Russia possess historical ties with Africa dating back to Soviet support for national liberation movements in the ‘50s and ‘60s, it has developed strong trade ties with many countries on the continent in recent years, with total trade between Russia and Africa surpassing U.S. trade with the continent. Primarily, African leaders are likely to be concerned about the conflict’s impact on inflation and global energy prices, as well as the thousands of African students trapped in Ukraine. While many governments are unlikely to take a stand on the issue, seeing little benefit, certain regional economic communities—like the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS)—did issue a communique condemning the Russian invasion.

South American Reactions and Impact

Finally, the Crisis Group report closes by looking at the impact of the crisis on Brazil, Mexico, and Venezuela, where the first two voted in favor of the resolution, while the third, Venezuela, remained suspended over non-payment of UN dues.

While Brazilian Foreign Minister Carlos Franca said on March 8 that the country would not take sides in the conflict, it has already voted to condemn the Russian invasion at the General Assembly. Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro—who had already been criticized by the West for meeting with Putin and voicing “solidarity” with Russia in the leadup to the war—has noted that Russian fertilizers are key for the country’s massive agribusiness sector and likely will not want to upset the relationship with Moscow. Furthermore, Western sanctions on Russian fertilizer are likely to affect Brazil’s soy production, one of the country’s major sources of income. With an election looming and Bolsonaro’s main opponent either remaining silent about Russia’s invasion, or condemning the U.S. and NATO for causing the crisis, Bolsonaro will also have to straddle the razor’s edge, avoiding criticism of Russia so as to not damage his country’s economy ahead of the October polls, while still avoiding further rebukes from the U.S.

In Mexico, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador had initially intended to continue strengthening his country’s ties with Russia, but the crisis has put a pause on the relationship which has seen Russia supply Mexico with needed COVID-19 vaccine. While the Crisis Group report argues that López Obrador criticized “all invasions”, he has avoided directly condemning Putin’s actions, and Mexico has in fact declined to impose sanctions on Russia for its provocative actions towards Ukraine, nor will it send any arms to Ukraine to defend against the invasion. As with other countries, especially those in the Global South, Mexico has had to deal with rampant inflation since the pandemic, a situation that will only be made more challenging with the ongoing war in Ukraine. Therefore, it is likely that López Obrador will be keen to thread the needle, aggravating neither its powerful northern neighbor, nor jeopardizing its place as Russia’s number two trading partner in Latin America.

Finally, the Crisis Group report closes with a look at how the Ukraine crisis has affected Venezuela, a longstanding Russian partner in Latin America. While Venezuela was unable to vote on the UN General Assembly resolution—as its voting rights are currently suspended over the non-payment of dues—it has become an important player in the global reaction to the Ukraine crisis, primarily because of the fact that it is home to the largest reserves of oil in the world. As such, Venezuela, like Iran, has become a key player in the global economy as the West looks to cut off its supply of Russian oil and find replacement sources. While the U.S. has previously tied any concessions on sanctions to progress on the Maduro governments negotiations with the country’s opposition, pressure has been building for the Biden administration to reciprocate Venezuela’s recent release of American prisoners in the hopes that a deal can be struck to increase Venezuela’s oil production and alleviate rising gas prices in the U.S. As noted by the Crisis Group authors, while the Maduro government will likely try to rhetorically remain supportive of Moscow, it will not want to do anything that could jeopardize future U.S. concessions, meaning that the government will have to be extremely cautious moving forward on the Ukraine file.

Europe and Beyond

While the Crisis Group’s report does provide an excellent look at both the international reaction and impact of the Ukraine crisis in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, in today’s world of global interconnections, a war in Europe has worldwide ramifications. Specifically, as has been noted by the European Council on Foreign Relations’ (ECFR) Pawel Zerka, the war in Ukraine is a test for Europe, as well. While countries such as Austria and Germany reacted with surprising firmness, with Austria co-sponsoring the UN General Assembly resolution condemning Russia and condemning Russian attacks on civilians—which it referred to as war crimes. Germany, meanwhile, reacted in an even more astounding manner, with new Chancellor Olaf Scholz announcing a dramatic reconfiguration of the country’s security architecture.

Meanwhile in France, the war’s escalation is further highlighting the relationship between Russia and far-right candidates in France’s upcoming presidential contest. Specifically, the Russian invasion has shined a spotlight on Marine Le Pen and Éric Zemmour—both of which have their own histories with Vladimir Putin—with Le Pen being greeted warmly by Putin in the past, and Zemmour longing for France’s own Vladimir Putin. While both candidates have condemned the invasion, Zemmour has come out and directly stated that, in Ukraine, “if Putin is guilty, the West is responsible.” While comments like that are only likely to weaken far-right candidates’ campaigns, and boost that of the incumbent Macron, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has clearly done a great deal to clarify security issues in the eyes of French voters in the leadup to April’s elections.

Elsewhere in Europe, Italy has seen the war reshape its domestic politics, though, as noted by ECFR’s Teresa Coratella, things had already been changing since Mario Draghi took over as Prime Minister. While three of the right-wing parties in the current governing coalition—Forza Italia, the Five Star Movement, and the League—have long sought to cultivate the “special relationship” that former Prime Minister Silivo Berlusconi had developed with President Putin, Coratella notes that virtually all Italian political leaders have joined in condemnations of Russian aggression towards Ukraine. Furthermore, Italy has joined in on Western sanctions on Russia, despite the fact that the country imports more than 40% of its natural gas from Russia, and has, as Prime Minister Draghi has stated, “more to lose compared to other European countries that rely on different sources.” Importantly, the European Union has pledged to aid Italy’s transition away from Russian gas, with roughly €59 billion being provided for green energy initiatives, though there are concerns that energy shortages as a result of the crisis could derail that path.

The Ukraine crisis also has had reverberations in the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, with the U.S. deploying 15,000 more troops to the area, bringing the total number of U.S. service members in Europe to 90,000. Alongside this, the U.S. has increased its supply of weapons and equipment to the region, sending 20 Apache helicopters and 8 Air Force F-35’s from Germany to the Baltics in order to help reassure NATO allies there. Finally, for the first time, the NATO Response Force had been activated, giving NATO Supreme Allied Commander Europe, Gen. Tod Wolters, a multinational land, air, sea, and special operations force that could quickly be deployed in support of the Alliance. While such troop increases are not nearly enough to defend against a full-blown Russian invasion of the Baltic state, such an invasion is not currently likely, as the bulk of Russian forces are engaged in Ukraine.

Finally, the conflict in Ukraine even extends past national borders and into space. While the U.S. and Russia have worked peacefully on the International Space Station for the past twenty-four years, recent statements by Dmitry Rogozin, the Director-General of Russian state space corporation Roscosmos, including sharing a video depicting the ISS being split apart, with the Russian apparently threatening to depart and leave U.S. astronaut Mark Vande Hei in orbit. While such threats are unlikely to be carried out (UPDATE: Rogozin has apparently confirmed that Vande Hei will come home as scheduled), Russia has already removed the flags of the U.S., UK, and Japan on a British OneWeb satellite launch, which was subsequently canceled, demonstrating how events on Earth can reverberate into space.

Final Thoughts

As mentioned above, in today’s globally interconnected world, it is unavoidable that conflict in one part of the world will ultimately echo throughout the planet. This is especially true when there is a war between Russia, the world’s eleventh largest economy, and Ukraine, supplier of more than 10% of the world’s wheat supply. While the war will clearly test Western solidarity, it is seemingly unavoidable that provoking the crisis has been an avoidable blunder for Putin and Russia.

While certainly not all Western partners voted in favor of the UN resolution condemning the Russian aggression towards Ukraine, it did force countries that have a relationship with both Russia and the West to reexamine whether or not they would like the relationship with Moscow to grow in light of Putin’s reckless actions. While it still remains to be seen if Europe and the U.S. are truly willing to take on the long-term economic consequences of cutting Russia out of all global markets, it does seem that, at least in the short term, the Western will to punish Putin for his actions is resolute. Moreover, while countries such as Saudi Arabia have seemingly reaffirmed their commitment to Russia during the crisis, some analysts feel that the Gulf countries will ultimately have little choice but to yield to U.S. pressure, as the rules-based Western international order and the U.S.’ Carter Doctrine has paid dividends for regional states in the past few decades. Because of that, it will be unlikely that they will desire to upset the apple cart in order to favor a Russia-led system, where those with power determine the fate of smaller states.

However the crisis in Ukraine ultimately shakes out, whether it is a Russian victory, defeat, or something in between, the aggression that Moscow has initiated towards Ukraine will have global consequences for the foreseeable future. While the United States has anything but clean hands when it comes to using its power to get its way around the world, the Russian aggression towards Ukraine is more naked in its ambitions, with little to no justification given by Russia beyond the fact that it feels that Ukrainian territory is Russia’s by right. Finally, while the fight between the West, China, and Russia the past few years has always been about the future of the West’s rules-based international order, the Russian invasion of Ukraine will only accelerate that battle, forcing countries to take a side between a rules-based order and an order—led by Russia—where might is the only thing that makes right.

2 thoughts on “The Russian War in Ukraine: A Truly Global Problem”