June 10, 2022

Back on January 27, U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin directed the Department of Defense (DoD) to develop a Civilian Harm Mitigation and Response Action Plan (CHMRAP) to, “improve [DoDs] approach to civilian harm mitigation and response and…inform completion of a forthcoming DoD Instruction (DoDI) on Civilian Harm Mitigation and Response.” As Secretary Austin said in the closing of his memo, “the protection of innocent civilians in the conduct of our operations remains vital to the ultimate success of our operations and as a significant strategic and moral imperative.”

With the U.S. mission in Afghanistan having finally wound down, Secretary Austin may well have had the protection of civilians (PoC) in armed conflict at the forefront of his mind. However, it may have also been due to concerns which were voiced by key members of Congressional oversight committees, such as Senators Elizabeth Warren of the Senate Armed Services Committee, Senator Chris Murphy on Senate Foreign Relations, or Representative Ro Khanna on House Armed Services. Secretary Austin’s recently renewed interest in the protection of civilians in armed conflict may have also come because of recent advocacy from non-governmental organizations such as the Center for Civilians in Conflict, Human Rights Watch, Airwars, the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, and others. Finally, the Secretary’s sudden interest in prioritizing the protection of civilians in armed conflict may have been due to unflattering examinations of collateral damage caused by the U.S. during its two decades of conflict in the Middle East.

Whatever the case may be for DoD’s renewed interest in the protection of civilians in armed conflict, the important thing is that the Pentagon is finally getting around to the inescapable fact that PoC issues are some of the most pressing in modern armed conflict—despite being largely ignored over two decades of U.S. fighting in Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, and elsewhere. Moving forward, if the Pentagon wishes to take steps to address long-standing problems with the U.S. military’s failure to uphold international humanitarian law and its responsibilities towards civilians living in war zones, it will need to do more to improve the protection of humanitarian organizations providing assistance to civilians in armed conflict.

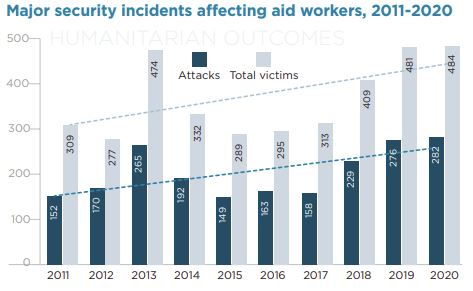

As noted in an excellent report from Larry Lewis of the CNA Corporation, “Improving Protection of Humanitarian Organizations in Armed Conflict,” from March of this year, “despite their vital importance to civilians and their protected status, humanitarian organizations—including hospitals, medical care workers, and organizations providing food and other essential supplies—are regularly attacked and harassed in armed conflicts.” While some of these attacks are deliberate or reckless, others are tragic mistakes that still result in horrific human consequences.

Therefore, while the protection of civilians in armed conflict is an important task—and one that the Pentagon seems to finally be taking with the seriousness it deserves—there not only needs to be a focus on the protection of civilian noncombatant residents of areas experiencing conflict, but on the protection of those administering vital medical and social services to those civilians living in conflict-affected areas. While the protection of civilians in U.S. and NATO military operations is something that has been discussed in these pages before, the protection of NGOs and humanitarian organizations in areas undergoing armed conflict is also worth some investigation, as those groups often not only provide vital services to civilians suffering through armed conflict, but they also provide critical, “perspectives regarding how civilians are affected by armed conflict, and…inform DoD’s approaches to mitigating and responding to civilian harm.” Therefore, it is worth diving into Lewis’ excellent March report for CNA Corporation to examine the ways in which the U.S. can better work with humanitarian organizations in order to reduce the frequency of such accidental (and sometimes deliberate) catastrophes.

To begin, Lewis notes that in order to avoid mistakes such as the Saudi-led coalitions’ allegedly accidental bombing of a Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) mobile clinic back in 2015, there not only needs to be the creation of improved communications channels between humanitarian organizations and militaries, but that more work needs to be done to strengthen deconfliction in military training; stronger tools need to be developed to help militaries recognize humanitarian organizations operating on the battlefield; and more work needs to be done to reinforce learning and accountability measures to reduce the risk of attacks on humanitarian organizations and the disruption of their humanitarian assistance operations.

When it comes to improving lines of communication between militaries and humanitarian organizations, Lewis argues that there are essentially two systems of communication that strengthen the protection of humanitarian organizations in conflict: humanitarian notification and civil-military coordination. Here, Lewis notes that while humanitarian workers are meant to be respected and protected under international humanitarian law (IHL), too often such individuals are under threat of physical attack or subject to restricted movement, despite having communicated to militaries in the area their locations and activities. As Lewis notes, these challenges can arise for a number of different reasons, ranging from incompatible notification systems among different humanitarian organizations, changing submissions formats and requirements, and slow reporting on and distribution of humanitarian organizations’ submissions to militaries—all of which result in a lack of trust between humanitarian organizations and the militaries they provide notification to.

In light of these challenges, Lewis argues, there is a need for a new humanitarian notification system (HNS) that can help address these challenges of civil-military coordination in order to provide militaries with the information that they need to avoid inadvertently targeting and striking humanitarian organizations operating in their theaters. As argued by Naysan Adlparvar in their intriguing August 2020 report, “Humanitarian Civil-Military Information-Sharing in Complex Emergencies: Realities, Strategies, and Risks,” the author states that, not only is, “information sharing between humanitarian and military actors…an increasingly common and required component in the delivery of humanitarian assistance,” but that, “the literature highlights that civil-military coordination and information sharing have been deeply impacted by the growing scale and nature of military involvement in humanitarian response since the US-led intervention in Afghanistan began in 2001,” and that while the presence of military grows in these situations, “so does the need for humanitarians to engage with them.” Furthermore, as argued by Paul A. Gaist and Ramey L. Wilson in a 2016 piece for National Defense University’s Joint Force Quarterly, the humanitarian community and the military, “must find mutually acceptable ways to establish productive working relationships or, at the very least, to co-exist in ways that do not increase the risks to our workers and/or our humanitarian objectives.”

As such, Lewis proposes the introduction of CNA’s new humanitarian notification system which aims to use blockchain technology to provide incorruptible records of information submitted to the system, creating an audit trail that can be leveraged by humanitarian organizations and militaries alike in order to promote better learning and accountability for attacks that do occur on NGOs and civilian organizations. However, as Naysan Adlparvar’s report notes, “one of the main concerns with notification is the problem of the so-called ‘black box’. It is very difficult to assess if humanitarian notification is working or not. In order to assess if humanitarian notification is effective, we need to know what is done with the information once it is received by parties to the conflict.”

To avoid the “black box” problem, CNA Corporation’s prototype HNS includes the total number of messages transmitted, compared against the total number of messages received by a particular party; the percentage of messages that were followed by an indication that it was received by the recipient; the average delay between submission of a message to a conflict party and the conflict party sending a receipt of that submission; the number of cases where humanitarian organizations were attacked over a particular period of time; and the number of cases where humanitarian organizations were interfered with or harassed over select periods of time. All of these metrics are meant to provide greater transparency and more accountability for civil-military communication, ensuring that both militaries and humanitarian organizations can have a better understanding of when and why militaries do not incorporate and act on location and activity data submitted by humanitarian organizations.

A new humanitarian notification system can also help strengthen deconfliction in military training and targeting processes, which is vital to avoid mistakes like the U.S. air strike on the MSF hospital in Yemen back in 2015. Up until this point, the avoidance of such tragedies has been reliant upon the creation of two major deconfliction processes: no-strike lists (NSL) and restricted target lists (RTL). No strike lists are a, “list of objects or entities characterized as protected from the effects of military operations under international law and/or rules of engagement,” while restricted target lists are a, “list of restricted targets nominated by elements of the joint force and approved by the joint force commander or directed by higher authorities.” Entities or objects on a restricted target list are those that may be struck, but that usually require that the specific timing or method of engagement be considered carefully, such as when striking a weapons cache that may result in secondary explosions which could damage nearby civilians or structures.

However, to truly understand the relative benefits and drawbacks of no-strike and restricted target lists, one must first understand how the lists are built, maintained, and then used by militaries and humanitarian organizations on the ground. As Lewis states, no-strike and restricted target lists are generally developed by intelligence analysts in coordination with other government agencies and humanitarian organizations that may have knowledge about the civilian objects, humanitarian organizations, or cultural sites in a potential target area. These protected sites include hospitals; schools; religious sites; critical national infrastructure such as dams and power stations; as well as cultural sites. As these objects are known quantities, targets on NSLs should include the location of the object on the list, its function, and a point of contact for the humanitarian organization operating it. Restricted target lists, on the other hand, contain politically sensitive targets which may be valid military targets, but that are either close to no-strike list entities, or could have a negative effect if attacked without caution, such as a weapons cache with the potential for secondary explosions. As such, an RTL should include why such a target is restricted along with special considerations that need to be included when attacking objects on or close to a restricted target list.

Such lists also need to be routinely maintained, with militaries providing humanitarian organizations a reliable, externally facing contact that can be reached at all times in order to ensure uninterrupted communication in times of crisis. In addition, Lewis argues, militaries must be required to acknowledge that they have received information submitted by humanitarian organizations, reducing the concerns of NGOs operating in the area as well as building trust between militaries and aid organizations.

Finally, these lists must be properly used, with military commanders ensuring that tactical decision makers have full access to these lists in order to aid in deconfliction and eliminate the chances for the type of tragedy that occurs when militaries accidentally attack humanitarian aid workers. While no-strike lists are usually housed at higher level headquarters, decisions are not confined to those headquarters, meaning that lower-level commanders and operators must have access to this vitally needed information; otherwise, situations such as the March 2017 air strike on Tabqa Dam in Syria—called in by U.S. special forces operators on the ground despite the dam being on the no-strike list—may very well happen again.

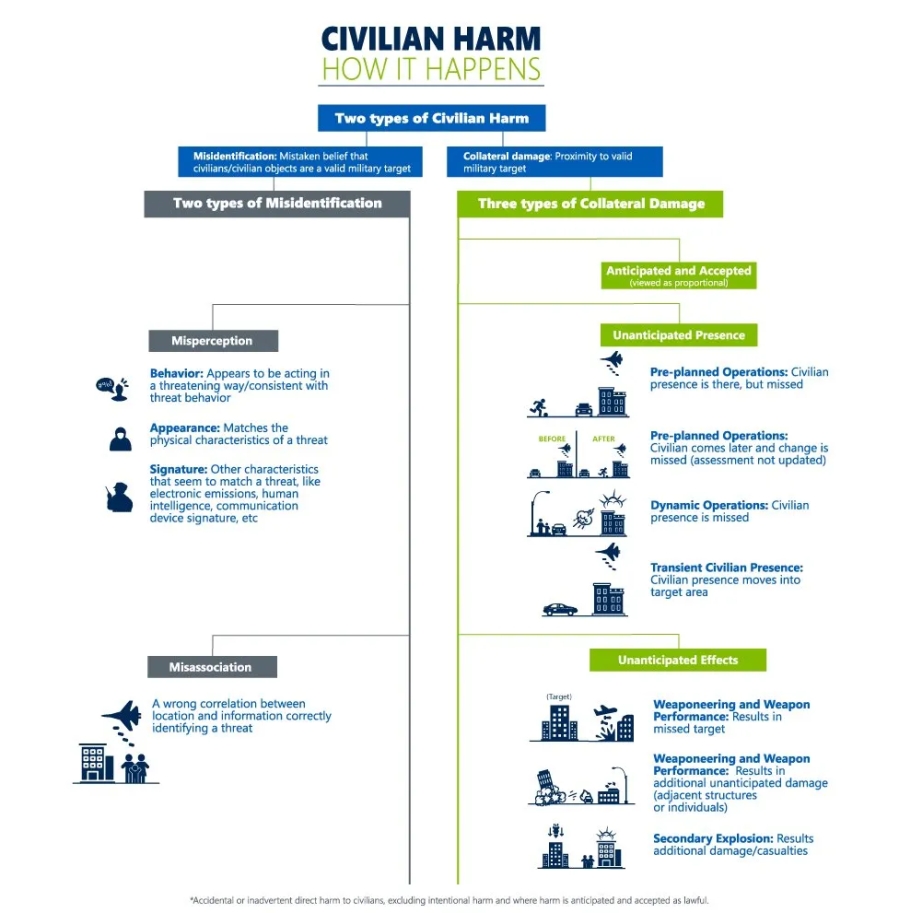

Improving the process of deconfliction through the development of a more well-defined humanitarian notification system would not only improve the creation of no-strike lists—as an HNS would standardize information received by militaries—but it would also improve pattern of life analyses, which utilizes surveillance tools to understand the movements and locations of individuals and groups over a given period of time. The inclusion of location and activity information from humanitarian organizations in the development of no-strike and restricted-strike lists are vital to protect against the misidentification of aid workers as potential military targets. Finally, Lewis argues that a more feature-rich HNS would help militaries integrate such information into their overall operational picture, giving them a better understanding of the overall operating environment.

In addition to better tools for deconfliction of humanitarian entities, Lewis also proposes that militaries develop better tools for recognizing humanitarian organizations in conflict-affected areas even without those groups’ input. As such, Lewis proposes that militaries make better use of artificial intelligence and machine learning to help military sensors and systems identify protected symbols like the Red Cross/Red Crescent or Blue Shield for cultural heritage sites. While the author acknowledges that this would not mean that such a system could not be abused—as the Iraqi military in 2003 misused, “protected symbols for impartial humanitarian organizations (e.g., Red Crescent), and place[d] equipment in protected sites—it would provide an added degree of safety for humanitarian organizations and their employees operating in conflict-affected areas.

In addition to the creation of these tools, Lewis also proposes that more be done to reinforce accountability for when mistakes do happen, whether due to deliberate or reckless behavior; or whether merely due to a failure to follow existing guidelines. To do so, he proposes that governments and militaries commit to tracking incidents more closely to confirm if and when strikes on humanitarian organizations occur; that governments and militaries work to determine exactly what happened when a strike on a humanitarian organization does occur, including Identifying trends that may indicate why such incidents happen in the first place and determining whether incidents happen more often via air strike or ground-based strike; that governments and militaries commit to providing compensation and assistance to victims, as well as communicating the results of internal investigations—even, and perhaps especially, when individuals are held to account for their mistakes; and that humanitarian actors, government, and security forces commit to regular dialogue in order to clearly communicate the challenges and concerns both the military and humanitarian organizations are experiencing. In general, a thorough accounting of any failures must be clearly and publicly communicated to aid organizations and the general public in order to build trust.

Promoting Partner Nation Accountability

However, it is not just during U.S. military operations when harm occurs to civilians and humanitarian organizations. As Lewis notes, harm done to aid providers by partner forces both damages U.S. goals in the region and undercuts the strategic success of partners by creating grievances among the civilian population, which can ultimately prolong a conflict. As such, the author proposes that nations providing security assistance work with their partners in four distinct ways to promote learning and accountability. Interestingly, many of the concepts that Lewis examines here have been advocated earlier in the excellent, “The Protection of Civilians in U.S. Partnered Operations,” by Melissa Dalton, Jenny McAvoy, Daniel Mahanty, Hijab Shah, Kelsey Hampton, and Julie Snyder, which is also highly worth a read on its own.

That process begins with creating a foundation for the protection of civilians and humanitarian organizations in all military assistance policies; and instilling PoC best practices in all engagement with security assistance partners, including incorporating PoC into efforts at the tactical, operational, and strategic levels so that it is incorporated into both mission planning and execution. The ultimate goal of such efforts is to ensure that civilian protection, as well as the protection of humanitarian organizations, is baked into how partner militaries operate at their most fundamental levels.

Relatedly, Lewis’s report argues that the U.S. needs to develop the capacity to promote civilian protection with partners through the provision of training materials including recommendations for the creation of civilian harm tracking units as well as recommendations for how to integrate PoC into operational planning. He also argues that when providing military assistance, the U.S. should develop approaches that influence a partner’s conduct during operations in order to promote civilian harm mitigation best practices and avoid needless abuse of civilians or aid workers. Finally, he states that in order to increase partners’ capacity for civilian protection, the U.S. should both develop better assessment tools to leverage historical data on civilian harm incidents as well as evaluate the capacity and willingness of partners to adopt best practices in order to mitigate such risks.

In addition to working with partner nations to promote the protection of civilians in their operations, Lewis argues that the U.S. should also work with regional leaders; multilateral organizations; major providers of military assistance such as France, the UK, Germany, Russia, and China; and cultivate international agreements which set baseline standards for the conduct of militaries engaged in armed conflict.

Finally, Lewis argues that the U.S. needs to do more to bolster partner capacity and the will to protect civilians and humanitarian organizations in conflict-afflicted areas. Part of such efforts include: developing tools that aid partners in protecting civilians, including developing technology that helps military sensors automatically distinguish targets on no-strike or restricted-target lists; taking into account partner motivations and concerns, devising ways to promote partner willingness to incorporate PoC into how its security forces behave—including demonstrating how protecting the civilian population can be operationally expedient; and developing tailored conditionality such as the U.S. “Leahy Laws”, which prohibit the U.S., “from using funds for assistance to units of foreign security forces where there is credible information implicating that unit in the commission of gross violations of human rights.” However, Lewis also notes that conditionality can be used positively, with a country providing assistance mandating training assistance or certain tools for the protection of civilians as a prerequisite for the provision of aid.

With a strong isolationist wing building in the G.O.P, the Biden administration actually has an opportunity to use Congressional Republicans’ diminishing support for international involvement as a cudgel to convince recalcitrant security sector aid recipients that their options are either: to shape up and put PoC and the protection of humanitarian organizations at the heart of their military operations and training; or risk losing Democratic Congressional support as they face down a potential Trump, Pence, or DeSantis administration that cares little about international security assistance programs.

General Accountability Issues

Lewis argues that even absent an active security assistance relationship, states can still take certain actions to promote accountability for harms done to civilians and humanitarian organizations. He states that states that engage in problematic or unlawful conduct should be named-and-shamed in UN reports such as the Secretary General’s annual report on Children and Armed Conflict. In addition, economic sanctions could be imposed on violators, including reductions in foreign assistance or outright cutoffs, asset freezes, revocation of most-favored-nation status, and prohibitions on credit, financing and investment. In addition, security assistance providers could begin to implement positive conditionality on their assistance programs, ensuring that recipients are aware from the outset that protection of civilians and protection of humanitarian organizations is a key priority for assistance providers. Finally, Lewis argues that crimes against civilians and humanitarian organizations can be pursued either through international tribunals such as the International Criminal Court, or even be responded to by the direct application of military force, such as when the U.S. coalition conducted air strikes on Syria in response to Bashar al-Assad’s violations of the Chemical Weapons Convention. However, Lewis is careful to note that such strikes often carry a mixed record—with Assad still likely in possession of chemical weapons despite those U.S. air strikes.

In Lewis’s estimation, therefore, it is the creation of a new humanitarian notification system—featuring standardized reporting protocols and formats that are easily accessible to militaries—that will best create an overarching infrastructure that ensures the protection of civilians and humanitarian organizations in conflict-riddled areas. For Lewis, while international humanitarian law is a good starting point, there is too often a failure to comply with it even by countries with strong rhetorical commitments to adhering to international law such as the U.S. Therefore, a comprehensive HNS will not only help militaries avoid tragic mistakes, but it will enable accountability after strikes do occur, ensuring that there is a better understanding of whether an incident is a tragic mistake or a more deliberate error. He argues that just as states acted in conjunction 1949 to ratify the original Geneva Convention, those states with a commitment to the protection of civilians and humanitarian organizations in armed conflict must now band together to develop better systems, which enable militaries to be more accountable for attacks on civilian targets. Failure to do so will only result in continued misery for civilians and aid organizations operating in conflict zones across the world.

Beyond the CNA Report – Issues with a Humanitarian Notification System for Deconfliction

One of the primary issues with the creation of CNA’s new prototype HNS is that such systems—albeit ones with less stringent reporting requirements—have done little when utilized in Syria and Yemen. In Naysan Adlparvar’s, Humanitarian Civil-Military Information-Sharing in Complex Emergencies, the author provides a strong critique of the system used in Syria in Yemen—the Humanitarian Notification System for Deconfliction (HNS4D). That system shared GPS data on the locations, activities, and personnel of humanitarian organizations with the warring parties for the creation of no-strike lists by each side of the conflict. However, a UN Board of Inquiry, “exploring the targeting of UN-affiliated humanitarian sites that had theoretically been deconflicted using HNS4D in Syria, determined that it was ‘highly probable’ that the majority of these sites were struck by the Syrian government or their allies.” Furthermore, one of Adlparvar’s research participants noted that, “let’s set aside the attacks on civilians for a minute and just talk about humanitarians. There is now a complete and total disregard of International Humanitarian Law (IHL), a.k.a. Law of Armed Conflict by some military actors. Russia and Syria definitively disregard IHL on a routine basis in Syria…We now have a complete and utter erosion of respect for IHL.”

Not only does Adlparvar’s report note the failure of humanitarian notification systems as they were used recently in Syria and Yemen, there are even concerns that such deconfliction systems are being misused by malicious actors like Syria, Yemen, and Russia to target humanitarian aid providers. While Lewis’ prototype HNS would provide a bit more insight into what countries are doing with the deconfliction data they receive, it would not be able to remove concerns from humanitarian organizations that by simply providing such location data that they might be targeted by countries with little respect for international humanitarian law.

Furthermore, there is the question of whether militaries have the capacity to absorb and process the scale of information that would be involved. While Lewis’ paper on CNA’s prototype HNS does not provide specifics on the number of data sets that it would contain, Adlparvar’s paper notes that the HNS4D in Yemen is responsible for vast amounts of data, with 64,000 sites interred into it. The fundamental question, therefore, is who exactly is going to be reviewing all of this information and comparing it against target lists as they are generated on a daily basis in a conflict.

As was noted in a February piece from Michael J. McNerney and Gabrielle Tarini for the Rand Blog, a recent, Congressionally mandated, review of DoD’s civilian casualty policies and procedures noted that, “DoD is not adequately organized, structured, or resourced to sufficiently mitigate and respond to civilian-harm issues. There are not enough personnel dedicated to civilian-harm issues full-time, and those who are responsible for civilian-harm matters often receive minimal training on those duties that they are expected to perform.” Furthermore, the RAND review found that civilian casualty tracking cells were often staffed by junior personnel with little actual training on the responsibilities they would be taking on. Therefore, if the U.S. military, one of the most well-funded in the world, spends this little time and effort on civilian casualty tracking and prevention, it is likely that countries with problematic track records such as Syria and Russia, will have even fewer resources to dedicate to such a system, making the uptake of a complex data tracking system like CNA’s prototype HNS even more unlikely to occur.

Another issue left unaddressed by Lewis is the fact that smaller and local humanitarian organizations, as was noted in a recent outcome document formulated by the European External Action Service, often, “have limited access to available data due to a lack of resources and/or information sharing. This is strongly linked to the lack of sustainable and quality funding for humanitarian organizations for a budget that comprises equipment, security measures (including acceptance), negotiations, and training (for international and local partners) which would reduce dependency over time.” While large, international NGOs such as Oxfam or Doctors Without Borders may have little problem procuring the systems and personnel necessary to participate in a humanitarian notification system, smaller, local NGOs may not have such funding available. Therefore, any humanitarian notification system must either be exceptionally cheap to access or subsidized in a way that permits all humanitarian organizations working in a given area to have continuous access to the system.

Yet another issue with the creation of CNA’s prototype humanitarian notification system is that such a process only really addresses actors with a genuine commitment to protecting civilians in the first place. While Lewis advocates everything from naming-and-shaming countries that do not abide by international humanitarian law to seeking proceedings at an international criminal court, it ignores the fact that countries that are willing to accept civilian casualties in their military operations are likely not going to be swayed by being placed on the UN Secretary General’s annual naughty list. Furthermore, frequent violators of international norms such as Russia and Syria are not signatories to the Rome statute, making them difficult to prosecute at the International Criminal Court; and even the United States, another all too frequent offender, is also not a Rome statute signatory.

Moreover, while deconfliction and the avoidance of attacks on humanitarian workers is certainly something that should be aspired to, there also needs to be systems in place to investigate what happens when the process fails. As argued by Annie Shiel and John Ramming Chappell in an April piece for the blog Just Security, “reviewing past cases of harm is also critical to any attempts to learn for the future…without a full picture of past civilian harm and the circumstances and causes of that harm, [DoD] cannot understand and learn from its mistakes.” Furthermore, as was argued by Martin Griffiths, UN Under-Secretary General for Humanitarian Affairs and Relief Coordinator in the summer of 2021, “allegations of serious violations of international humanitarian law must be systematically and independently investigated, and perpetrators held to account. War crimes that go unpunished embolden perpetrators to commit further violations.” As mentioned above, while some U.S. combatant commands have civilian casualty (CIVCAS) tracking cells, not all do. Therefore, the creation of units to track civilian harm, at least at each of the U.S.’ six geographic combatant commands, is a step towards the U.S. being able to better investigate incidents of harm to civilians or humanitarian organizations if and when they do occur.

Closing Thoughts

In totality, the creation of a humanitarian notification system that incorporates incorruptible audit trails, and provides the ability for investigators to gain insight into why incidences of harm to humanitarian organizations and their employees, would be a welcome addition to the PoC arsenal, as it would not only provide accountability for mistakes, but would hopefully prevent such tragedies from occurring in the first place. However, while Lewis and CNA’s proposed new HNS would be valuable, its creation alone will not suddenly render the battlefield completely hospitable to humanitarian organizations. Instead, more must be done in order to protect aid workers working in conflict-affected areas.

For American decision makers, one complicating factor in the struggle to reduce civilian harm is simply the sheer size of the U.S. military; as Lewis himself noted in a November 2021 piece for Just Security, “DOD is the largest bureaucracy in the world (followed by China’s PLA and WalMart), and has the largest budget by far of any military on the planet,” and that it is therefore, “notable that while the Services, Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD), and the Joint Chiefs of Staff have leadership positions for a wide variety of issues, there is no leader in DOD working solely to mitigate civilian harm. While there are leaders who have this issue in their portfolio, they have many competing priorities and almost no resources or authority.”

In light of that fact, and if the U.S. wishes to do more to prevent inadvertent attacks on humanitarian organizations in conflict-zones, it will need to do more than create a new humanitarian notification system. Instead, DoD needs to incorporate PoC and the protection of humanitarian organizations at the center of operations planning. As experts recently explained to the United Nations Security Council, “today’s unprecedented global need for humanitarian assistance — in concert with escalating violence against those providing it — requires robust action.” Therefore, countries need to ensure that these aid organizations can operate free from fear of targeting by parties to the conflict.

In 2009, as General Stanley McChrystal assumed command of NATO International Security Assistance Force – Afghanistan, he discovered that the war was going poorly, as, “several high-visibility CIVCAS events, along with dozens of other smaller escalation-of-force incidents over the past few years, damaged ISAF’s credibility as it battled the Taliban for the ‘hearts and minds’ of the Afghan people.” He therefore wrote in his Tactical Directive to troops in theater that:

“Our strategic goal is to defeat the insurgency threatening the stability of Afghanistan. Like any insurgency, there is a struggle for the support and will of the population. Gaining and maintaining that support must be our overriding operational imperative – and the ultimate objective of every action we take. We must fight the insurgents, and will use the tools at our disposal to both defeat the enemy and protect our forces. But we will not win based on the number of Taliban we kill, but instead on our ability to separate insurgents from the center of gravity – the people. That means we must respect and protect the population from coercion and violence – and operate in a manner which will win their support.”

He further concluded that, “we must avoid the trap of winning tactical victories – but suffering strategic defeats – by causing civilian casualties or excessive damage and thus alienating the people,” and that while, “the carefully controlled and disciplined employment of force entails risks to our troops – and we must work to mitigate that risk wherever possible. But excessive use of force resulting in an alienated population will produce far greater risks. We must understand this reality at every level in our force.”

So too must militaries around the world refrain from using force that results in harm being done to aid groups that provide essential services to civilians living in conflict zones. While the protection of civilians residing in conflict zones must obviously be the starting point, decision makers must also ensure that aid workers are similarly protected, as humanitarian aid is essential to ensuring that victims of war survive the conflict. Under the Geneva Convention and customary international humanitarian law, nations have a responsibility to ensure the protection of civilians and aid workers operating in conflict areas.

Therefore, the creation of new humanitarian notification systems for conflict zones is merely the starting point. Countries must also do more to strengthen the protection of humanitarian organizations, from better resourcing civilian and humanitarian worker harm tracking efforts to more thoroughly investigating attacks on humanitarian aid workers after they occur. As Lewis concludes in his paper, “better protection of civilians, and of the humanitarian organizations that act on their behalf, is an attainable goal.” However, to reach that goal, there needs to be a great deal more commitment from military leaders and national decision makers to truly incorporate the protection of humanitarian organizations into the processes that guide tactical decisions on the ground in conflict zones. To paraphrase Secretary Austin, the protection of humanitarian organizations in the conduct of U.S. operations remains vital to the ultimate success of U.S. operations, and as a significant strategic and moral imperative.

One thought on “Humanitarian Notification and Beyond: The Protection of Aid Organizations Operating in Conflict Zones”