July 1, 2022

According to most media reports, President Biden will be heading to the Middle East later next month—making stops in Israel, the West Bank, and finally Saudi Arabia—where he will allegedly be looking to mend fences with Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman after calling the kingdom a “pariah” on the campaign trail, and vowing to end U.S. weapons sales to the country. The trip comes as oil prices have hovered near $120 per barrel—a huge jump from an average of $71 per barrel in December 2021—and with Saudi Arabia looking unlikely to boost output anytime soon. As such, the Biden administration is in a tough spot—with prices at the pump for the average consumer remaining above $5 per gallon—forcing the administration to request a suspension of the federal gas tax despite no guarantee that the savings would actually be passed on to consumers. In all, the Biden administration is in a political quandary, with mid-term elections looming this fall. As such, there is a lot of anticipation surrounding the President’s upcoming visit to Riyadh, and calls for Biden to use the occasion of the trip to reset the U.S.-Saudi relationship.

It is in that environment in which, on June 22, the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) released, “The Case for a New U.S.-Saudi Strategic Compact,” by Steven A. Cook and Martin S. Indyk. The report—which recognizes that the U.S.-Saudi relationship has fundamentally changed since Franklin Roosevelt and King Abdulaziz Al Saud first agreed to a partnership back in February of 1945—argues that even as the U.S. attempts to draw down its presence in the Middle East in order to “pivot to Asia”, Saudi Arabia has actually become more important, not less. Cook and Indyk state that the U.S. needs to, “recognize that during the decades-long transition away from fossil fuels, Saudi Arabia’s role in stabilizing oil prices will remain critical,” and that, “Saudi Arabia would need to recognize that American support for its security will require greater respect for American interests and values.” In short, they argue, “a fundamental renovation of the basic bargain that has lasted more or less for eight decades is required.”

However, while Cook and Indyk are certainly correct that a reevaluation of the relationship is something that the Biden administration should be seriously pursuing, their arguments that the U.S. should make sacrifices around its values in order to avoid losing influence in Saudi Arabia and the region are ultimately unpersuasive, as the report fails to place its advocacy of rapprochement in the proper context. While it is certainly true that the U.S. still remains affected by Middle East insecurity and the concomitant fluctuations in oil and gas prices, Cook and Indyk’s analysis places too much emphasis on what the U.S. needs from Saudi Arabia and not enough on what the kingdom needs from the U.S.

Therefore, to better understand how the Biden administration should handle its upcoming meeting with the de facto ruler of Saudi Arabia—and the potential drawbacks to what Cook and Indyk propose—it is best to start with a brief review of how the authors view the U.S.-Saudi relationship, historically, as well as look at their recommendations on how to proceed.

The Origins of the U.S.-Saudi Arabia Relationship

Cook and Indyk begin their report with a brief assessment of the relationship over its nearly eighty years of existence. They note that, from the start, the relationship has always been fundamentally transactional, with the U.S. providing the Saudi royal family promises of security for the kingdom in exchange for the continual flow of oil needed for American industry. However, while simple on paper, that arrangement has not always been smooth. To that end, the authors note the Saudi involvement in the Arab oil embargo following the 1973 Arab-Israeli War (Yom Kippur War) which saw Arab producers cut off exports to the U.S. to protest U.S. military support for Israel in the war against Egypt and Syria.

However, this period was followed by a long period of rapprochement in the late 1970s and early 1980s as the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan prompted U.S. President Jimmy Carter to proclaim the “Carter Doctrine”, which stated that, “an attempt by any outside force to gain control of the Persian Gulf region will be regarded as an assault on the vital interests of the United States of America, and such an assault will be repelled by any means necessary, including military force.”

The authors note that, following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the CIA, together with Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence Agency (ISI), and Saudi intelligence services worked to fund, arm, and equip the Afghan mujahideen via a program called Operation Cyclone, which saw Saudi Arabia commit to match every U.S. dollar spent fighting the Soviets. However, it should be noted that while the bulk of Saudi funding went to arms purchases, “the remainder was distributed as direct cash payments among the leaders of the Peshawar Parties and influential clerics, politicians and commanders by Prince Turki and the Saudi embassy in Islamabad,” and that, “out of the Peshawar Parties the strictly fundamentalist, Wahhabi-prone Ittehad-e Islami bara-ye Azadi-ye Afghanistan (Islamic Union for the Freedom of Afghanistan), led by Abdurrasul Sayyaf, and the militant Islamist Hezb-e Islami-ye Afghanistan (Islamic Party of Afghanistan), under the leadership of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, emerged as the key clients of the Kingdom’s Afghan policy and received the bulk of the direct official donations.” Yet another key player the Saudis worked with in Afghanistan was Osama bin Laden, who used his money and experience in the construction trade to build a series of bases where mujahideen fighters could be trained by Pakistani and American advisors.

The 1980s saw the U.S.-Saudi relationship blossom further, with the Saudis quietly supporting Iraq against their enemy, Iran; and with the U.S. providing weapons, military advice, battlefield intelligence, and diplomatic support to Iraq in order to counter the likelihood of Iranian victory. However, things began to turn sour with the events surrounding the release of the U.S. hostages being held at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran. Reagan’s deal with Iran to provide the country with weapons in exchange for hostages being held in Lebanon—as well as to counter growing Soviet influence inside Iran—saw Riyadh become disillusioned that the U.S. would assist the Iranian war effort despite the two sides ongoing enmity.

In spite of this brief period of dissatisfaction, the August 2, 1990 Iraqi invasion of Kuwait—which saw Baghdad move approximately 100,000 troops to the border of Saudi Arabia, opening up the possibility of invasion—was the catalyst to turn the relationship back around. In addition to the troop buildup, contemporaneous reports noted that Iraqi aircraft in southern Iraq were observed loading chemical weapons onto aircraft, and that U.S. officials believed that the move was done as a threat to both the U.S. and Saudi Arabia not to intervene. In response to the threat, Saudi Arabia reached out to the U.S., who quickly dispatched a few brigades—including one from the 82nd Airborne and elements of the 101st Airborne. Thomas L. McNaugher of the Brookings Institution noted at the time that the deployment was, “intended to reassure Saudi Arabia that any attack would precipitate a war with the United States.” In sum, the U.S. would deploy an expeditionary force of over 500,000 Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen, and Marines to Saudi Arabia as part of Operations Desert Shield and Storm.

After the war, however, the relationship would again take a turn for the worse under President Clinton, especially as Crown Prince Abdullah became frustrated by the administration’s inability to forge a final peace after the Oslo Accords. Relations were further damaged with the recalcitrance of Saudi Minister of Interior Prince Nayef bin Abdulaziz and his grudging cooperation into the U.S. investigation of the Khobar Towers bombing in 1996, which raised questions about the complicity of Saudi Shiite extremists. Tensions between the two sides were further inflamed with the outbreak of the Second Intifada in 2000, when Saudi Arabia felt that the Bush White House gave Israel a green-light to respond to the uprising with unrestrained violence. While the relationship was somewhat smoothed by President Bush’s subsequent public support for a Palestinian state, it showed that the U.S.-Saudi relationship could grow fragile even under a Republican in the White House.

Post 9/11

With fifteen of the nineteen hijackers possessing Saudi citizenship, the 9/11 attacks saw public support for the U.S.-Saudi relationship nosedive as some of the public, as Saudi Arabia went from a net +1 positive rating to a -37 negative rating between September 2001 and February 2002. Furthermore, the U.S.’ 2003 invasion of Iraq aggravated the Saudis, who viewed Saddam Hussein as a necessary counterweight to Iran and saw the U.S. invasion as greatly expanding Iran’s influence in Iraq at the Saudi’s expense. As was written by David Ottaway of the Wilson Center, during this period, “for the first time, the U.S. government became extremely critical of the Saudi educational system and the kingdom’s ultraconservative Wahhabi religious establishment. The White House and Congress even pressed for radical changes in the kingdom’s monarchical rule.” Furthermore, in Cairo in June of 2005, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice announced that the U.S.’ pursuit of stability at the expense of democracy in the Middle East was over, stating that the U.S. was going to support, “the democratic aspirations of all people,” in the region. The Saudi response to which was, “ shock and anger. Crown Prince Abdullah…huddled together with Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak to plot a common defense and denounce Bush’s freedom agenda,” noting that Arab governments would follow their own path in keeping with their, ‘Arab identity.’”

The relationship again soured under the Obama administration, which openly supported the Arab Spring movements and called for Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak to step down in the face of widespread protests against his rule. As such, King Abdullah began to fear that in the event of a potential revolt in his own country, that the U.S. President would demand that he leave. Furthermore, as was noted by the Gulf Research Center’s Shahram Chubin in a 2012 paper, “the differing reactions of Iran and Saudi Arabia to the Arab Spring have further exacerbated the Iran-Saudi rivalry,” with a key factor being Iranian involvement in Iraq triggering concerns about the extension of Iran’s influence into Iraq. While the Obama administration vetoed the Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorism Act, Congress overrode his veto, clearing the way for the victims of 9/11 to sue Saudi Arabia on the claim of official government complicity with al-Qaeda. Moreover, while Saudi Arabia officially voiced cautious approval of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) with Iran, its leaders were clearly frustrated by the lack of consultations with them on the initial agreement. Finally, in the closing days of its tenure, the Obama administration decided to modify its military support to the kingdom due to Saudi Arabia’s human rights violations in the war in Yemen.

Finally, under the Trump administration, relations warmed once again, with the new president choosing Riyadh as the site of his first foreign visit; signaling his intent to withdraw from JCPOA; and resuming U.S. arm sales to Saudi Arabia for their war in Yemen. Moreover, in January of 2020, the U.S. carried out a drone strike at Baghdad International Airport that killed IRGC Commander Qasem Soleimani. What’s more, while the U.S.-Saudi connection has seemingly always had its ups-and-downs since its inception in the 1940s, since the beginning of the Obama administration, the relationship has become more starkly politicized, with stark divides over how to deal with Saudi Arabia emerging between Republicans and Democrats in Congress as well as the American public. Further shaking up the relationship has been the rise to power of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman—a figure initially seen as a reformer but who has become somewhat of an international pariah due to his alleged complicity in the murder and dismemberment of Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi as well as the 2022 mass execution of eighty-one individuals despite assurances that the country was completing major legal reforms.

Reassessing the Relationship in 2022

With relations between the U.S. and Saudi Arabia becoming more fraught as President Biden took office, Cook and Indyk argue that it is a good time to reevaluate the relationship in light of today’s geopolitical situation. To that end, the authors look at the two sides partying ways; reviving the old oil-for-security compact; or trying to create a new, more durable partnership.

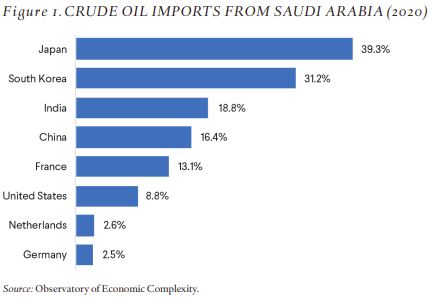

Here, the authors note that while U.S. dependence on Saudi oil is unlikely to return anytime soon—especially as the U.S. has imported fewer barrels per year from the Kingdom every year since 2012—there is still the major issue that U.S. partners such as Japan (39%), South Korea

(31%), India (18%), and France (13%) import large amounts of Saudi oil, meaning that Saudi Arabia still retains a good deal of leverage over the U.S. via its partners. In addition, as the biggest “swing producer” of oil—with the ability to reduce or increase production of oil by over a million barrels per day—giving the country the ability to use oil prices as a geopolitical cudgel if it wants to. Cook and Indyk further argue that this dependence will not be a temporary situation, as the West’s efforts to move towards renewables is moving too slowly to be able to spurn Saudi Arabia’s hydrocarbons anytime over the next two decades. Indeed, one can see that Saudi Arabia views the situation this way, with its continued capital investments in the oil sector.

Cook and Indyk further argue that, as custodians of Mecca and Medina, Saudi Arabia is the leading Muslim nation, and, as such, has a responsibility to promote a more moderate and tolerant form of Islam around the world. Instead, Saudi Arabia has historically exported a radical form of Wahhabist Sunni Islam, which has been detrimental to Muslim societies around the globe, as its promotion of sectarianism and rivalry with Iran helped fuel conflicts which have devastated Syria, Yemen, and elsewhere. While Mohammed bin Salman has instituted some reforms in an attempt to promote a more moderate and tolerant form of Islam at home, his efforts have had a questionable degree of success. Furthermore, efforts to transform the Saudi economy away from oil—shifting the burden for economic growth onto the private sector—have resulted in “vanity megaprojects” over real efforts to cope with the country’s “Dutch disease.” If those economic reforms continue to fail, and trillions are wasted on high-cost, experimental projects such as Saudi Arabia’s planned eco-city on the Red Sea, it could result in a domestic backlash that threatens the regime and regional stability.

Another factor that cannot be ignored in assessing the state of the U.S-Saudi relationship in 2022 is the U.S.’ planned retrenchment from the region. Cook and Indyk argue that even as the U.S. turns its eyes towards Asia, it cannot extricate itself from the Middle East without a security framework that fills the huge void left by the departure of American forces from the region. Here, the CFR authors argue that, as such, Saudi Arabia’s’ strategic importance to the U.S. increases as they are the only country with the diplomatic and military heft to provide a strategic balance to Iran outside of Israel. Therefore, Cook and Indyk propose an “Abraham Accords Axis” of Saudi Arabia, Israel, GCC countries, Egypt, Jordan, Morocco and Sudan that could promote regional stability and allow the U.S. to shift its attention to the Indo-Pacific. While the Palestinian issue still remains a thorny one, there are indications that Saudi Arabia may be willing to abandon their insistence on establishing a Palestinian state before normalization can occur with Israel.

However, Cook and Indyk are careful to note that permitting Saudi Arabia to become the preeminent remaining player in the Middle East—alongside Israel—would permit the Crown Prince to possibly double-down on his worst instincts, such as the Saudi-led intervention in Yemen and the blockade of Qatar, which have done almost as much to damage regional stability as anything Iran has attempted in recent years, short of its nuclear program. Cook and Indyk acknowledge that, with the U.S. pivot to Asia, Mohammed bin Salman has little reason to become a reliable partner. They argue that, instead, the U.S. must show Saudi Arabia that it can rely on the U.S. security guarantee if Saudi Arabia is to behave more responsibly in its own backyard.

Drawbacks of Current Options

The CFR authors argue that, left to his own devices, the Saudi Crown Prince will simply continue to hedge his bets, keeping his country’s OPEC+ oil production commitments with Russia and deepening ties with China. They further argue that a continued U.S. decoupling from the region would result in a Saudi Arabia that drifts ever more into China and Russia’s orbits, especially in terms of arms imports and security cooperation. If that were to occur, Cook and Indyk assert, the Biden administration and Congress would likely adopt an even more critical view of Saudi Arabia’s human rights record and the war in Yemen, further straining the relationship. However, they contend that such a separation could create the space for improving Saudi-Israeli relations as well as to mitigate the rhetorical strains on the Biden administration’s “values-based” foreign policy by eliminating the need to create carve outs for Saudi behavior.

However, the authors note that this drift has been temporarily disrupted by the war in Ukraine, with the two sides seemingly needing to come to some sort of reconciliation in order to stabilize global energy markets. For Cook and Indyk, the two sides coming to a “realist” understanding would involve setting aside Saudi human rights violations in order to return to a security-for-oil relationship; though they do acknowledge that such a reconciliation would likely require Congressional authorization of new arms sales to Saudi Arabia.

Despite these benefits, the authors ultimately argue that such a reset to the old status quo would unlikely achieve the results that the Biden administration is seeking; especially as it faced Congressional criticisms for the abandonment of its values-based foreign policy, and arms sales, which already were previously blocked by the House, would be difficult to push through without causing chaos amongst the progressive caucus. Furthermore, letting the Saudi Crown Prince have free rein would likely result in further blunders such as the war in Yemen, ultimately weakening the relationship in the long-term by creating further long-term strains on the partnership.

Elements of a New Strategic Compact

As Cook and Indyk view the alternatives of separation and a return to the old status quo as untenable, they thus propose a reconceptualization of the original U.S.-Saudi understanding, where both sides make parallel commitments in order to demonstrate each side’s reliability to the other. To begin, they state that the U.S. would need to clarify its security commitment to Saudi Arabia, entering into a Strategic Framework Agreement similar to what exists between the U.S. and Singapore. Such an agreement would provide a strong U.S. commitment to enhance security cooperation with Saudi Arabia in order to deal with common threats and promote regional stability. Such an agreement could include defense cooperation through the Saudi provision of facilities for U.S. vessels, personnel, and equipment; the conduct of bilateral and multilateral exercises in the region; conducting policy dialogues to exchange strategic perspectives; cooperation in disaster management; building counterterrorism capacity in Saudi Arabia; and cooperation against the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, amongst other things.

The authors propose if such a commitment were to be reciprocated by the Saudis, then the U.S. could commit to immediate consultations in the event of an imminent security threat against the kingdom, which would address concerns that the Biden administration did not do enough in response to Houthi attacks on Saudi oil facilities in the Spring of 2021 and, through its lifting of the foreign terrorist organization (FTO) designation on the Houthis in Yemen. The authors also argue that the U.S. could borrow elements from the Taiwan Relations Act and commit to treating any attack on Saudi Arabia as a threat to the security of the region, and of grave concern to the United States. While none of that would be tantamount to a NATO Article 5 guarantee, it would allow Saudi Arabia to feel more secure in the knowledge that the U.S. will come to its defense when needed.

The authors propose that, in exchange, Saudi Arabia and Mohammed bin Salman would have to take a series of steps in order to provide the Biden administration with the political benefits it would need to justify such a hefty security commitment to such a domestically unpopular country. These include Saudi Arabia making an open-ended commitment to use its swing production capability to stabilize global energy prices at reasonable levels; that Saudi Arabia come to an understanding with the U.S. on a timetable for ending the war in Yemen; that the kingdom take more steps to normalize relations with Israel; and that the Saudi Crown Prince would have to take public responsibility for the Khashoggi murder, ensuring that those physically responsible for the killing were “brought to justice”—whatever that means in a scenario wherein the U.S. has a good deal of certainty that Mohammed bin Salman was ultimately behind the murder.

Problems with the New Strategic Compact

Ultimately, it is this section of the report where Cook and Indyk’s analysis fundamentally breaks down, as it seems to be predicated on a fundamental misunderstanding of the exact nature of the relationship, as well as a fatal naivete about the man who will likely be leading Saudi Arabia for the next half-century.

To begin, while Cook and Indyk’s report is valuable as a way to understand many of the current strains on the U.S.-Saudi relationship, it does not paint a clear enough picture about the extent of Saudi reliance on the U.S. security guarantee and partnership. Moreover, it somewhat over inflates overall U.S. dependence on the kingdom. From joint maritime security cooperation missions and exercises in the Arabian Gulf that address insecurity around the Arabian peninsula to joint air operations and training in support of those maritime elements and even efforts to “train, advise, and assist” Saudi Arabia’s’ regular armed forces, the U.S. is doing quite a bit to transform the Saudi’s, “multilayer structural and organisational problems,” in defense.

As was noted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Anthony Cordesman in a March 2018 analysis, it had been clear that Saudi Arabia had, “been spending far too large a portion of its economy on security priorities that have yielded uncertain results.” For a country that spent 8% of its GDP on security and defense in 2020, and is the second largest importer of foreign arms in the world over the past four years, Saudi Arabia will want to ensure that it gets the most of of its new, predominantly-American equipment, especially as it needs U.S. trainers and advisors to instruct its soldiers on how to properly use their new equipment.

What’s more, just as India has been faced with the difficulty of weaning itself off of Russian-made weapons—in particular, the need for a steady supply of spare parts for the 46% of Russian-made equipment it has imported in the past four years—so will Saudi Arabia run into difficulty if it were to decide to spurn U.S. equipment in favor of Russian or Chinese equipment. As was noted in a piece in the Intercept back in 2019, that year, a highly classified document produced by the French Directorate of Military Intelligence, “shows that Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are overwhelmingly dependent on Western-produced weapon systems to wage their devastating war in Yemen. Many of the systems listed are only compatible with munitions, spare parts, and communications systems produced in NATO countries, meaning that the Saudis and UAE would have to replace large portions of their arsenals to continue with Russian or Chinese weapons.” Indeed, as Rachel Stohl of the Stimson Center said to the Intercept in the same 2019 article, “you can’t just swap out the missiles that are used in U.S. planes for suddenly using Chinese and Russian missiles,” as, “it takes decades to build your air force. It’s not something you do in one fell swoop.”

Furthermore, despite President Biden’s distaste for the Crown Prince, in June 2021, the administration reported to Congress that there were still around 2,700 U.S. troops in the country deployed to protect U.S. interest against hostile action by Iran or its proxies. Additionally, U.S. forces in CENTCOM, as of June 2021, still provided U.S. monitoring of, “Yemeni territory for incoming projectiles targeting Saudi territory,” which gives Riyadh early warning in the event of attack. Moreover, the U.S., through commercial contractors, continued to provide maintenance and sustainment services to the Royal Saudi Air Force (RSAF) which is essential to keep Saudi aircraft in the air. Finally, as was also pointed out by Elias Yousif of the Security Assistance Monitor, such support includes $9 billion for F-15 support, $1.8 billion for “aircraft follow-on support and services” including logistics support for RSAF aircraft, engines, and weapons; and $106.8 million for maintenance and support to support the Royal Saudi Land Forces Aviation Command’s rotary-wing fleet, engines, avionics, missiles, and more.

However, U.S. security assistance does not solely consist of foreign military sales (FMS) and international military education and training (IMET), but also includes security and counterterrorism cooperation programs. According to the Congressional Research Service, these programs include the Office of the Program Manager-Ministry of Interior (OPM-MOI), which is, “a Saudi-funded, U.S.- staffed senior advisory mission that embeds U.S. advisors into key security, industrial, energy, maritime, and cybersecurity offices within the Saudi government, including with the Ministry of Interior and Presidency for State Security,” which, ““facilitates the transfer of technical knowledge, advice, skills, and resources from the United States to Saudi Arabia in the areas of critical infrastructure protection and public security.” Moreover, in tandem with these efforts, the U.S. Army Material Command-Security Assistance Command (USASAC) oversees a Saudi Ministry of Interior Military Assistance Group (MOI-MAG), under which, U.S. personnel provides to Saudi Ministry of Interior security personnel, “security assistance training to include marksmanship, patrolling perimeters, setting up security checkpoints, vehicle searches at entry control point, rules of engagement toward possible threats and personnel screening,” as well as courses similar to the Army Basic Instructors’ Course, basic officers’ course, airborne and flight training, and military police training.

What’s more, the U.S. has conducted a number of naval operations in recent years in and around the Persian Gulf both to support international standards regarding freedom of navigation, but also to directly deter Saudi rivals Yemen and Iran. More recently, as was noted by Vice Admiral Brad Cooper, Commander of U.S. Naval Forces Central Command and Commander of the U.S. Fifth Fleet, “in terms of cooperation with Saudi Arabia, [the U.S. has] for decades and we continue to have an excellent relationship with Saudi Arabia. We have a very large contingent of Saudi navy personnel here at headquarters as part of both the Combined Maritime Forces as well as the International Maritime Security Construct, the operational arm of which is called Task Force Sentinel.” He further notes that the two sides work together on a daily basis, conducting maritime exercises in the Red Sea with the Saudi navy. Finally, the mere presence of the U.S. Fifth Fleet, U.S. Naval Forces Central Command (NAVCENT), and the multinational Combined Maritime Forces (CMF) has helped Saudi Arabia crack down on arms smuggling to the Houthis in Yemen as well as conduct counter-piracy missions in the region.

In sum, therefore, it will be extremely difficult for Saudi Arabia to quickly and easily wean itself off from U.S. support, even if it wished to jump straight into the arms of Russia or China, especially with Russia stuck in a quagmire in Ukraine and with China entering into historic, long-term agreements with Saudi Arabia’s chief rival, Iran. Furthermore, as was readily acknowledged at the outset of Cook and Indyk’s report, U.S. dependence on Saudi oil just is not what it once was, with the U.S. even going weeks in 2021 where it did not import any oil from the kingdom.

Additionally, while it is true that the European market will certainly be looking to replace Russia’s spot as the continents’ main hydrocarbons supplier, as of now, the EU only imports around 7% of its crude oil from Saudi Arabia, the same amount imported from the United Kingdom. With Russia the EU’s main supplier of 1.2 million barrels per day of refined oil products, meeting European demand would eat into almost the entirety of Saudi swing production capacity. Furthermore, such an increase would not even address the EU’s demand for natural gas—which is around 155 billion cubic meters per year—especially as Saudi Aramco has not yet figured out how to develop and commercialize its Jafurah gas field reserves. What’s more, Aramco has yet to expand its domestic gas infrastructure, meaning that any attempt to deliver natural gas to Europe would be complicated by the lack of a gas export facility on Saudi Arabia’s Red Sea coast or a pipeline connecting directly to Europe, each of which will take years to complete; years that Europe does not have.

Therefore, while the situation in Ukraine has made European energy dependence on Russia untenable, the United States should comfortably feel that it is currently offering Saudi Arabia as much as—if not a great deal more than—Saudi Arabia is offering the United States. While Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman certainly retains the ability to make things even more difficult in the region by ramping up his country’s proxy war with Iran in Syria, Yemen, and elsewhere, a renewal of the relationship, if it is just to avoid malign behavior from the Saudi Crown Prince, would send a terrible message to the international community about what the United States is willing to tolerate from its partners.

To be clear, negotiating a new U.S.-Saudi Strategic Compact, which sacrifices American values in order to secure a twenty-year supply of subsidized hydrocarbons, would be the height of cynicism. It would fundamentally communicate that Mohammed bin Salman’s behavior in ordering the murder of Jamal Khashoggi, launching a humanitarian catastrophe in Yemen, and silencing dissent at home is fine with Americans as long as they get a dollar per gallon relief at the gas pumps. Such cynicism can only embolden a figure like Mohammed bin Salman to go further with his repression at home, safe in the knowledge that his major security partners may find his behavior distasteful—just not so much that they will do anything in particular about it.

Another reason to be skeptical of a renewed U.S.-Saudi Strategic Compact would be the potential damage done to the Palestinian cause. While Cook and Indyk propose that a new Middle East architecture—which would build on the security cooperation framework of the Abraham Accords—would bring together Saudi Arabia with Israel and, “provide a robust platform for promoting regional stability that would enable the United States to shift from a dominating role in the regional balance to a supportive one,” there is the thorny issue that the Saudi Crown Prince has stated that there can be no normalization between his country and Israel absent a resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. While indications are that it is King Salman who is more of a barrier to Israeli-Saudi normalization, and that full diplomatic ties will not be possible until Prince Mohammed takes the throne, the fact that the Crown Prince is willing to consider abandoning his country’s traditional support of the Palestinian cause simply further demonstrates the Crown Prince’s purely transactional nature. Those that abandon all principles as the landscape changes around them are not the best people to conduct long-term security compacts with—as they are likely to abandon the deal with the U.S. when times get tough or a better offer comes along from a country such as China.

What’s more, a potential “Abraham Accords Axis” ignores the fact that public opinion in both Saudi Arabia and the U.S. opposes deeper ties between the two sides. As was revealed in a poll conducted by the Washington Institute for Near East Policy from November 2020 only 41% of the Saudi public call the UAE and Bahrain’s normalization with Israel somewhat or very positive, while 54% have negative responses to the deals. Furthermore, support for the Abraham Accords dipped in a June 2021 poll to just 36% of Saudi respondents.

The public opinion situation is not that much better on this side of the Atlantic, either. While polling data from the Chicago Council on Global Affairs notes that while 45% of Americans view the Saudis as a partner with which the U.S. must strategically cooperate, the country receives just 37 out of a possible 100 points in the Chicago Council’s thermometer rating. For perspective, the Chicago Council’s data on the U.S. major rival, China, puts that country’s thermometer rating at 33 out of 100, a similarly poor ranking.

Another essential problem with the U.S.-Saudi relationship is the simple fact that if Saudi Arabia really is an American client state, the U.S. certainly does not get the value it needs out of the relationship. In Christopher Shoemaker and John Spanier’s classic text on patron-client relationships, the authors define six types of relationships, from patron-centric to influence parity and even client-centric. The U.S.-Saudi relationship would likely fall into Shoemaker and Spanier’s third type of relationship—influence parity—wherein a client in possession of a major natural resource, such as oil, is able to exert a large degree of influence in the relationship, as the patron will be willing to go to great lengths to keep the client on their side. At the same time, a client in a high-threat environment will be willing to go the extra mile to keep the relationship.

However, what is being proposed by Cook and Indyk would lean more towards a client-prevalence or even client-centric model, wherein the largely threat-free client has huge influence over the patron, as the patron is focused on major strategic objectives which can only be achieved through client participation. While Saudi Arabia is not entirely threat-free with a possibly nuclear-armed Iran looming nearby, a Saudi Arabia that makes peace with Israel and retains a robust U.S. security guarantee would have much less to fear than it has in the past. Similarly, as Aly Zaman noted in their doctoral thesis examining the U.S.-Pakistan patron-client relationship, the U.S.-Saudi relationship is one where the client is, “Deemed by the patron to be of significant strategic importance,” thus making them, “likely to receive more assistance,” while being, “less compliant in fulfilling the patron’s objectives.” Zaman further notes that, “this is especially true of relationships in which the patron regards the client’s cooperation as vitally important for the attainment of the patron’s core security interests.”

Moreover, Zaman remarks that, “as long as the patron’s own strategic interests necessitate a degree of client cooperation, it will find itself compelled to keep the relationship going, thereby giving the client continued room to deviate from the patron’s script to an extent where it can pursue its own national interests with relative impunity, confident in the knowledge that while its defiance might lead to occasional tensions with the patron, its continuing strategic importance will prevent a complete rupture and consequent termination of material assistance.” While discussing the U.S.-Pakistan relationship, Zaman could have easily been discussing the U.S.-Saudi one. By making Saudi Arabia one of the largest global recipients of U.S. arms, the U.S. communicated to Saudi Arabia that it could act with impunity. Instead of a recalibration of the bilateral partnership, Cook and Indyk’s new Strategic Compact would merely double down on the existing security-for-oil relationship, and by removing the Saudi-Israeli tensions, actually make Saudi Arabia more secure and, thus, more likely to pursue its own national interests with impunity.

Finally, there is the point that there is a blatant contradiction at the heart of Cook and Indyk’s new Strategic Compact. As was noted by Andrew J. Bacevich in his book, America’s War for the Greater Middle East: A Military History, the 1980s Carter Doctrine, “represented a broad, open-ended commitment, one that expanded further with time,” which, “implied the conversion of the Persian Gulf into an informal American protectorate, and that, “defending the region meant policing it.” As such, it is hard to square the Biden administration’s professed desire to pivot to Asia with a massive, open-ended commitment to police the entire Persian Gulf region for Saudi Arabia.

Ultimately, while Cook and Indyk’s instincts to attempt to arrest the downward spiral in the U.S.-Saudi relationship are laudable, their conclusion that the U.S. must provide Saudi Arabia with a more robust security commitment than the one already being given not only ignores the imbalance in relationship in regards to the relative benefits provided, it ignores the fact that such a renewed commitment would constrain U.S. desires to pay greater attention to the Indo-Pacific. Similarly, Saudi behavior in recent years—including its hedging towards Russia after the Russian invasion of Ukraine and sidling closer to China—has demonstrated that Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman should not be considered a trusted interlocutor for the U.S. While international affairs often forces countries to partner with those with which they have major differences, asking the U.S. to enter into a broad, open-ended commitment to Saudi security simply in exchange for an end to the war in Yemen and cheaper—it is not defined specifically what Cook and Indyk mean when they say Saudi Arabia must agree to use its swing production ability to standardize oil prices at “reasonable” levels—oil and gas would, at the minimum, be a bargain balanced strongly in the Saudis favor. When adding in the antipathy the American public shows towards the future Saudi monarch—and his demonstrated track record of human rights abuses—and the country more generally, it would be better to accept some temporary economic pain now rather than double down on a bad relationship with a murderous authoritarian autocrat.

One thought on “The Perils of a New U.S.-Saudi Strategic Compact”