July 8, 2022

With the ongoing war in Ukraine, Russia and China deepening their ties, rising nationalism and authoritarianism around the globe, and increasing incidences of extremist terrorism on the Euro-Atlantic periphery, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization is facing one of the sternest tests of both its cohesion and purpose since at least the end of the Cold War. Furthermore, the past few years had seen Alliance cohesion become strained, as transatlantic political cohesion frayed in the face of rising nationalism and authoritarianism from within the Alliance itself.

To see if the Alliance is able to surmount these difficulties, it is perhaps best to begin with a look at last week’s NATO summit in Madrid, with a specific focus placed on the release of the long-anticipated NATO 2022 Strategic Concept—the Alliance’s first since the Lisbon summit in 2010. The document—which outlines NATO’s core tasks as: deterrence and defense; crisis prevention and management; and cooperative security—is a statement of NATO values and commitments over the next decade. However, it is one that, in the end, fails to do much of substance outside of refocusing the Alliance’s threat perceptions towards Russia, China, and the Euro-Atlantic periphery.

The 2022 NATO Strategic Concept is broken down into four main sections covering: the Alliance’s principles; its present strategic environment; three subsections dealing with NATO’s core tasks; and a brief statement of future aspirations. It begins by arguing that the key purpose of the alliance is to ensure collective defense of its members, which are bound by common values. The Strategic Concept states that Allies will not only focus on enhancing resilience and their technological edge over peer competitors, but that Alliance members will work together to address issues like climate change, human security, and implementation of the women, peace, and security agenda.

The Strategic Concept then proceeds to an examination of today’s contested strategic environment, specifically noting that unlike in 2010’s analysis, the Euro-Atlantic area is not at peace, with Russian aggression shattering the norms that underlie the European security order. The document further notes the continuing rise of authoritarians around the globe, many of whom are investing in military capabilities, including the development of nuclear weapons and associated advanced delivery systems. NATO’s new strategy document notes that these authoritarian governments not only invest in strengthening their own military capacity, but they also interfere in Allied democratic processes, targeting its citizens through the use of hybrid tactics.

The Strategic Concept therefore situates Russia as the Alliance’s most direct threat, arguing that under Putin, the country looks to establish spheres of influence, using conventional, cyber, and hybrid means available at its disposal. Furthermore, with its global reach, Russia has the ability to destabilize NATO’s East, South, and High North. While the 2022 concept argues that the Alliance does not wish to confront or threaten Russia, it says that its members will continue to strengthen deterrence, enhance resilience, and support their partners in order to counter malign Russian interference in the Euro-Atlantic periphery.

Beyond Russia, the Strategic Concept also notes the threats posed by transnational terrorism; conflict and instability in the Middle East and North Africa; cyber threats; and China’s increasing ambitions and coercive policies. While remaining open to engagement with China, the document makes clear that China seeks to subvert the rules-based international order, especially in areas such as human rights.

Finally, the document closes its discussion of the present strategic environment by noting that the proliferation of emerging and dangerous technologies (EDTs) amongst allies and competitors will alter the future nature of conflict, as technology continues its ever-increasing impact on battlefield success; that the erosion of the arms control and nonproliferation architecture harms strategic stability; and that climate change is a threat multiplier, exacerbating conflict, fragility, and geopolitical competition across the globe.

Accomplishing NATO’s Core Tasks

The Strategic Concept then proceeds to outline how the Alliance will act on its core tasks of deterrence and defense; crisis prevention and management; and cooperative security. It is here, however, where the document, which was vague in its general outline of the problems facing NATO, really shows its limitations. While filled with buzzy phrases like “360-degree approach”, the overall document is far too light on the types of specifics that would make this a truly useful strategic document. Indeed, if the new Strategic Concept is, as was submitted by the Stimson Center’s Sydney Tucker, “the most significant deliverable from the NATO Summit” in Madrid, then the Alliance may well be in a great deal of trouble.

As was argued in an excellent piece on the war in Ukraine by the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Anthony Cordesman from April of this year, “a 30-country alliance cannot be revitalized by setting broad strategic goals that are not based on some form of net assessment and that do not measure current and projected capability by country in terms of mission and threat.” However, that is exactly what the Strategic Concept’s three sections on executing the Alliance’s core tasks essentially amount to. The document is full of vague generalities that, while good-intentioned, are ultimately worthless when it comes to ensuring that NATO is able to meet its goals. Furthermore, despite the NATO 2030 Reflection Group’s recommendation that, “NATO should consider creating a new net assessment office, composed of both military and civilian staff and reporting directly to the Secretary General, with the mission of examining NATO’s strategic environment on the basis of agreed threats and challenges across the whole spectrum of military and non-military tools,” the Strategic Concept does not seem to be based on any kind of holistic assessment of the tools and capabilities belonging to both Alliance members and their potential adversaries.

Instead, what the document presents is a series of more generalized goals for the Alliance, with strong adjectives seemingly substituting for real strategy. For instance, under the core task of deterrence and defense, the concept notes that NATO will, “employ military and non-military tools in a proportionate, coherent and integrated way to respond to all threats to our security in the manner, timing and in the domain of our choosing,” without being clear what “proportionate” even means in such a context beyond the obvious definition in international law. Furthermore, the document does not define what type of “non-military tools” need to be available in order for NATO to respond to a potential security threat.

The remainder of the section on deterrence and defense is littered with similar usage of unspecific language. For instance, it argues that NATO, “will deter and defend forward with robust in-place, multi-domain, combat-ready forces, enhanced command and control arrangements, prepositioned ammunition and equipment and improved capacity and infrastructure to rapidly reinforce any Ally,” without outlining the specific types of troops that would need to be made available to ensure that forces are “multi-domain” nor does it make clear what would need to be done to ensure that troops are “combat-ready”. Furthermore, when it says that NATO, “will adjust the balance between in-place forces and reinforcement to strengthen deterrence and the Alliance’s ability to defend,” it does nothing to specify a minimum troop number that will need to be forward-deployed in specific countries in order to be ready to deter or defend against an enemy attack.

While these critiques may seem like pedantic nit-picking, statements that NATO, “will expedite our digital transformation, adapt the NATO Command Structure for the information age and enhance our cyber defenses, networks and infrastructure,” are essentially meaningless without a specific definition of the types of equipment and capabilities that will need to be acquired by Allies in order for the Alliances cyber defenses to be deemed “secure”.

While it is certainly laudable that the document pledges to enhance readiness, integrate command structures, uphold maritime security, make secure use of space and cyberspace, pursue a more coherent approach to building Alliance-wide resilience, and invest in defenses against chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) threats, without an accompanying analysis of how NATO’s main competitors—Russia and China—stack up in those areas relative to the Alliance, the document is really nothing more than a restatement of Alliance values.

The only area in which the document has anything approaching the level of specificity required to make this a useful strategy is in the area of cooperative security. That sections reaffirms the Alliance’s commitment to its Open Door policy, resists third party interference in membership decisions, calls for the continued integration of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, and Ukraine into the Euro-Atlantic community, and argues for enhanced NATO-EU cooperation on resilience, climate change, EDTs, human security, the Women, Peace, and Security agenda, and military mobility.

While a political document that gets all thirty NATO countries operating off of a similar political script is valuable in a world where consensus among Allies is getting harder and harder to achieve, the Strategic Compass, as written, will never be much more than that. Furthermore, there is a worry that the document’s lack of specificity— which carried over from the 2010 document—will permit Alliance some members to continue to be lackadaisical in their approach to the changing security environment. Specifically, the failures of the 2010 document to recognize the rising threat emanating from Russia may end up being repeated in the 2022 document with the overall failure to concretely outline the elements of a military deterrence posture in Eastern Europe that will give Putin pause before considering a potential attack.

New Concepts and Old Problems

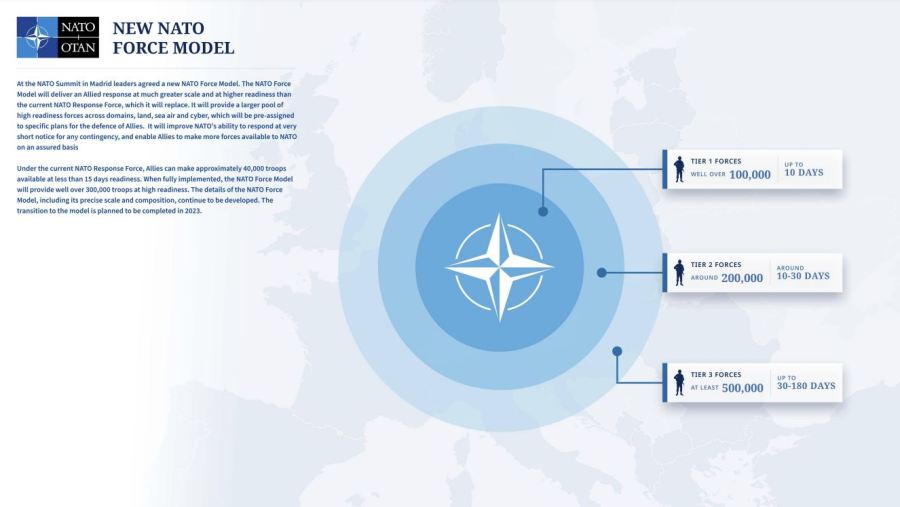

While the Madrid Summit did come with some particulars to back up the language of the Strategic Concept, such as increasing the number of enhanced Forward Presence (eFP) battlegroups in Eastern Europe from four to eight and increasing the NATO Response Force (NRF) from 40,000 to 300,000 troops—which will now be held at higher levels of readiness—it was generally light on concrete details. Furthermore, there are already indications that some Alliance members doubt whether NATO can pull off such a new model, which would require much greater financial and troop commitments from member states. As the Atlantic Council’s Chris Skaluba remarked, “NATO deserves the benefit of the doubt until details are clearer, but there was some skepticism on the ground in Madrid about the ability to balance clear short-term deterrence requirements with this new, longer-term vision.”

But the problems with the Strategic Concept do not stop there. As noted by the Royal United Services Institutes’ (RUSI) Ed Arnold in a July 1 commentary, the Strategic Compass’ identification of Russia as the primary regional threat is commendable, but it fails to provide a, “vision and a realistic timeframe for understanding the parameters of the NATO-Russia confrontation.” As Arnold notes, the documents that historically buttressed the European security order since the end of the Cold War—from the Helsinki Final Act of 1975 to the NATO-Russia Founding Act of 1997—are all but defunct. Thus, the Strategic Concept’s inability to outline which elements of the post-Cold War European security architecture remain valid and vital to the future relationship with Russia is a major failure. With the hope that the war in Ukraine will not be a conflict that drags on for a decade or more, a more forward-looking strategic planning document should have more to say about how to handle Russia once it is hopefully defeated in Ukraine.

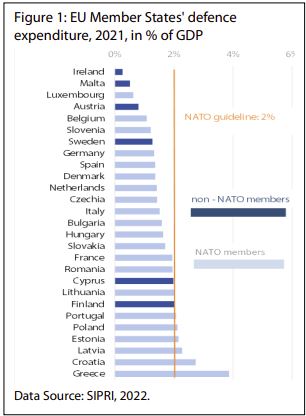

As was pointed out by the RUSI commentary, yet another troubling example of the Strategic Concept’s troubling lack of specificity is that—while arguing that a strong Ukraine is vital for Euro-Atlantic stability—the document not only fails to outline exactly how Alliance members will increase NATO common funding to cover the increase in eFP battalions and the NATO Response Force; it also fails to grapple with how the organization’s membership will sustain funding to rebuild Ukraine despite inflationary pressures and the ongoing economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Bringing Back NATO’s Sword and Shield?

If the 2022 NATO Strategic Concept is still far too vague to be genuinely functional as a strategic document, it might therefore be useful to examine some recommendations on how it could be made more useful. One recommended approach comes from CSIS’ Sean Monaghan, whose June 2022, “Resetting NATO’s Defense and Deterrence: The Sword and the Shield Redux,” argues for the Alliance to bring back some valuable elements from prior strategic concepts in order to meet today’s challenges.

Monaghan chronicles the history of NATO’s seven Strategic Concepts, examining how the Alliance moved from a strategy of deterrence by punishment—through the threat of the use of U.S. nuclear weapons—to a more mixed strategy, combining deterrence by punishment through the use of strategic bombing and conventional military power with deterrence by denial through effective forward defense. These strategies were later combined into what was called “The Sword” and “The Shield”. The concept, which dates to the late 1950s, saw the sword representing the, “nuclear retribution of the Strategic Air Command, missiles and other weapons systems capable of reaching deep into the Soviet Union,” as a contemporaneous New York Times report noted. Meanwhile, NATO’s shield consisted of, “land, air and sea units [protecting] Europe from being overrun while the sword is being unsheathed and is striking at the vitals of the enemy.” In essence, the sword represented deterrence by punishment, whereas the shield represented deterrence by denial through forward defense.

Monaghan notes that the change in NATO strategy arose from a growing nuclear parity between the U.S. and Soviet Union, as well as the Berlin and Cuban crises in the late 1950s and early 1960s. These events led some individuals, such as U.S. Defense Secretary Robert McNamara to conclude that nuclear superiority did little to deter and deal with problems short of all-out nuclear war. A reliance on massive retaliation ultimately undermined the deterrence architecture, however, because it put the onus on NATO to decide whether to begin an all-out nuclear war—a step Soviet leaders realized the West would be unwilling to take—thus leaving a deterrence gap. In McNamara’s estimation, only a stronger non-nuclear posture would make up for this deficiency in Western will.

Thus, the fourth NATO Strategic Concept outlined that, should deterrence fail and Russian aggression towards Eastern Europe occur, that there were three types of response options open to NATO. These included direct defense, or, “physically preventing the enemy from taking what he wants.” The argument was that, “full options for direct defence exist when NATO can successfully counter any aggression, at whatever place, time, level and duration it occurs,” and that the forward deployment of troops on land and at sea is the best deterrent. Another type of response option would be deliberate escalation, which, “seeks to defend aggression by deliberately raising but where possible controlling, the scope and intensity of combat, making the cost and risk disproportionate to the aggressors’ objectives and the threat of nuclear response progressively more imminent.” Elements of deliberate escalation included opening more conventional battlefield fronts; the demonstration or selective use of nuclear weapons; or even selective nuclear strikes against suitable military targets. Finally, the third, and most escalatory option, would be a general nuclear response, which, “contemplates massive nuclear strikes against the total nuclear threat, other military targets, and urban-industrial targets by required.”

To bolster NATO’s direct defense “shield”, the fourth Strategic Concept therefore called for, “sufficient ground, sea and air forces in a high state of readiness, committed to NATO for prompt, integrated action in times of tension or against any limited or major aggression.” This required a capability for rapid, massive reinforcement of NATO’s forward posture in Eastern Europe, not too unlike today’s NATO Readiness Initiative (NRI).

Monaghan notes that however successful the Cold War-era Strategic Concepts were, after the 1990s, the Alliance moved away from deterrence as NATO’s primary purpose, focusing instead on a range of tasks in and around its periphery, including: crisis management, conflict prevention, and cooperative security. However, the Russian invasion of Crimea in 2014 seemed to alert decision makers as to how badly Vladimir Putin had undermined the Alliance’s deterrence policy, necessitating a return to Cold War-era NATO policy. As such, Monaghan argues that it is time for a return of NATO’s sword and shield.

Just as RUSI’s Ed Arnold said that the 2022 Strategic Concept lacked a realistic timeframe for understanding the NATO-Russia confrontation, Monaghan argues that NATO should turn to the Alliance’s first Strategic Concept, which argued that as, “precise Soviet intentions are not known and cannot be predicted with reliable accuracy,” that, “for military planning purposes…it is essential to consider maximum intentions and capabilities.” In addition, in order to revitalize NATO’s sword and shield, Monaghan argues that if the NATO assessment of Russian intentions are similar to NATO’s past assessments of the Soviet Union, then the Alliance should re-adopt its combination of robust strategic nuclear forces to deter attack along, coupled with a forward deployment of significant numbers of NATO troops to Eastern Europe. However, Monaghan is careful to note that in resurrecting NATO’s sword and shield, a number of modernization considerations would need to be made to update the strategy, including: asking whether NATO’s strategic nuclear forces are resilient to threats from EDTs; what role total defense might play in deterring both conventional and hybrid attacks; and what role does NATO assistance to non-Alliance members support its deterrence efforts.

Monaghan’s sword and shield concept rests on the idea that in a world where Russian intentions are increasingly unpredictable, nuclear weapons are simply not enough to deter a potential threat to Eastern Europe since their deterrence effect relies on a belief that the West will preemptively use them. As such, NATO will need to ask itself if it has the financial and political strength to do what is necessary to rebuild not only its nuclear sword, but its massive, forward-deployed, deterrence shield.

Military Mobility, Readiness, and Deterrence by Denial

One of the biggest questions raised by both the 2022 Strategic Concept and Monaghan’s revitalized sword and shield for NATO is how the Alliance will meet the goal of resuscitating its strategy of deterrence by denial. While the 2022 Strategic Compass calls for expanding both the NATO Response Force and the Alliance’s enhanced Forward Presence battalions in Eastern Europe, it fails to address enduring challenges that prior strategies were unable to overcome—the thorniest of which are Europe and the U.S.’ ongoing military mobility challenges. While military mobility issues in Europe have been addressed in these pages a number of times, it is worth noting how they specifically impact NATO’s new Strategic Concept. As stated by former Supreme Allied Commander Europe, General Curtis Scaparotti, to an Atlantic Council virtual event in April of 2020, NATO has, “looked at rapid deployment as being really our strategy for deterrence and defense in Europe,” noting that, “to do that we have to have ready forces, we have to set conditions with equipment forward…[and] we also have to reinforce at the speed of conflict. For that to work you have to have mobility available.”

NATO’s 2018 Readiness Initiative—which is also sometimes known as the “four thirties”—called for Allies to be able to deliver thirty battalions, thirty air squadrons, and thirty naval combat vessels to a potential front in Eastern Europe within thirty days. However, while NATO states that Alliance members had, by 2020, “generated more than ninety per cent of the forces required,” not enough has been done to enable the rapid flow of such forces to a hypothetical future front in the east.

As was remarked on in a 2021 Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA) report from Heinrich Brauss, Ben Hodges, and Julian Lindley-French, “since the end of the Cold War much of the road, rail, air, sea, and port infrastructure that enabled NATO forces to move rapidly across Western Europe has diminished, together with the facilities that also enabled the safe transit and secure reception of U.S. and Canadian forces.” Furthermore, the CEPA authors note that, “in spite of recent progress…Europe is by no means close to meeting the military mobility challenge…despite there being an implicit acknowledgement that rapid and assured military mobility (together with Europe’s ability to act as an effective first responder) is central to credible defense and deterrence.”

What makes these issues more troubling is the fact that—as was pointed out in the CEPA report, as well as a 2020 report from the Atlantic Council—NATO was already encountering difficulties in meeting the NRI’s goals of flowing thirty battalions of troops to Eastern Europe in a potential conflict scenario. Therefore, it raises fundamental questions about how a NATO Response Force of 300,000—ten times the amount of troops the original NATO Readiness Initiative calls for—could possibly flow into Europe in a short enough timeframe to make a difference in a potential conflict.

While the RAND Corporation’s now famous 2016 wargame showed Russian forces entering Tallinn and Riga within sixty hours of the start of a potential conflict between NATO and Russia, those hypotheses must, of course, be fundamentally reexamined after Russian failures to advance swiftly in Ukraine. However, it does raise the inescapable point that any potential conflict between NATO and Russia will likely take place directly next to Russian territory—as well as Russian-controlled Belarus—giving Russia the mobility advantage in the early days and weeks of a fight. Furthermore, while the 300,000-strong NATO Response Force will undoubtedly consist of large numbers of European troops, U.S. forces will likely make up somewhere between ⅓-½ of the NRF troop commitment, meaning that a large portion of the force will have a much more difficult logistical challenge than simply traversing continental Europe.

Further complicating the picture for U.S. land forces making the long trip to a potential front in the Baltic states or Poland is that it is highly questionable as to whether those troops would have the right equipment needed in order to immediately enter the fight. As was noted back in the early spring, the U.S. Army had, for the first time, activated its Army Prepositioned Stock-2 sites, tasking the 405th Field Support Brigade to full equip an entire armored brigade combat team (ABCT) with the main battle tanks, armored fighting vehicles, light tactical vehicles, tucks, generators, and the rest of the unit’s supporting equipment. However, while a laudable achievement, the fact that the Army was boasting about its ability to outfit a unit of around 4,500 soldiers is concerning when one considers the fact that in a potential fight between Russia and NATO’s Response Force, such logistics units would likely need an ability to equip somewhere between 95,000-145,000 more U.S. troops within a very short time period.

This reinforcement will be further challenged by the fact that, “even if all the MSC Surge Fleet and MARAD Ready Reserve Force ships are able to activate, DoD may fall short of the cargo capacity it needs for potential conflict scenarios,” as was noted in a 2020 report from Bryan Clark, Timothy A. Walton, and Adam Lemon of the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. Adding to these reinforcement challenges is the fact that, according to a 2021 Government Accountability Office (GAO) review, while the Defense Department has conducted or sponsored eleven classified and sensitive studies on the ability of the U.S. military to transport equipment and personnel in a contested operational environment, it has not tracked the number of recommendations that have actually been implemented into Department planning. More specifically, the review asserts that, “training requirements for the U.S. citizen mariners who are contracted to crew surge-sealift ships that might have to operate in contested environments have not been evaluated and updated as appropriate,” noting that, “because sealift accounts for the majority of military equipment that is transported for major military operations, the ability of sealift to operate in a contested environment is critical to supporting the U.S. military’s global operations.”

Furthermore, as was elucidated by Vice Admiral Ricky L. Williamson, Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Fleet Readiness and Logistics at the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, in a statement before the House Armed Services Committee back in March of 2020, “over the next 25 years, ~60% of the sealift fleet will reach end of service life.” In essence, not only does the U.S. have a present inability to seamlessly deliver troops and equipment to Europe in the event of a potential conflict with Russia, but that capability will degrade going forward unless there is a fundamental recapitalization of the U.S. strategic sealift fleet. What’s more, while the EU has approved €330 million to adapt the Trans-European Transport network for dual civilian and defense use, large infrastructure projects typically have long lead times, raising questions about whether such modernization projects would be completed in time for a potential NATO conflict with Russia—especially if one emerges out of the war in Ukraine. Ultimately, not only would these challenges undermine the NATO Readiness Initiative and the NATO Response Force’s deterrence value, they highlight a major overall deficiency in NATO’s new Strategic Concept.

Finally, there is the issue of interoperability, or the lack thereof in some Eastern European states. As noted by CSIS’ Anthony Cordesman in a February 2022 report, “most of the former Warsaw Pact states…have barely begun effective conversion to forces that are fully interoperable with NATO forces, and they have generally failed to maintain anything approaching their former strength when they were supported and supplied by the [former Soviet Union].” Furthermore, Cordesman continues that, “the progress the U.S. and NATO’s older members have made in being able to rapidly deploy major forces forward to deter and defend on the territory of NATO’s new members is also generally limited. NATO has made some collective improvements here, but many older European members now lack much of their former ability to deploy forward, and their force posture lacks many elements of the readiness and sustainability to take such action.” What’s more, a July 2020 commentary by active-duty U.S. Army officer Josh Campbell for War on the Rocks, notes that, despite U.S. pressure, many European armies face gaps in their conventional capabilities, which, “could limit the quality of forces assigned to the NATO Readiness Initiative.” Furthermore, Campbell states that as NATO member states, “use different command and control systems, communications devices, and specialty equipment,” there are issues of interoperability at the tactical level that make it difficult for such forces to quickly integrate into a coherent NATO fighting force in a potential conflict.

Whereas Campbell argues that NATO needs to establish a, “clear definition of readiness for forces allocated under the NATO Readiness Initiative and adopt organizational structures that allow these units to plan and train together regularly in peacetime,”—and the 2022 Strategic Concept does make three references to improving the military interoperability of NATO forces— the document’s overall lack of specificity as to how it will achieve that goal is, once again, a glaring error.

Closing Thoughts

In sum, while the 2022 Strategic Concept is full of big, broad ideas about how to improve Euro-Atlantic defense, it is troublingly light on detail. Furthermore, the strategy document fails to address some of the most basic questions regarding how exactly it will meet major goals such as creating a 300,000-strong Response Force that is able to credibly deter a potential aggressor in NATO’s eastern periphery. Not only that, but the Strategic Concept does little to illuminate how the Alliance intends to navigate the post-Ukraine war landscape with Russia, especially in the possible event of Ukraine’s defeat or even a regime change in Russia following a Russian defeat. Finally, the document contains few verifiable metrics with which to measure the ultimate success or failure of the Strategic Concept over its likely decade-long lifespan.

Ultimately, while such strategy documents are vital, they should not simply be generalized statements of principle, but rather, clearly articulated action plans that demonstrate how the Alliance is going to get from today’s problems to tomorrow’s solutions. Without a net assessment of respective capabilities, a coherent picture of the post-war relationship with Russia, and an understanding of the Alliance’s military mobility deficiencies, the Strategic Concept is a strategy document with little strategy and it lacks the coherent details that would enable it to transform its words into any kind of coherent reality.