September 16, 2022

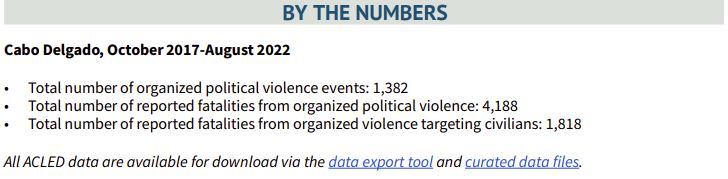

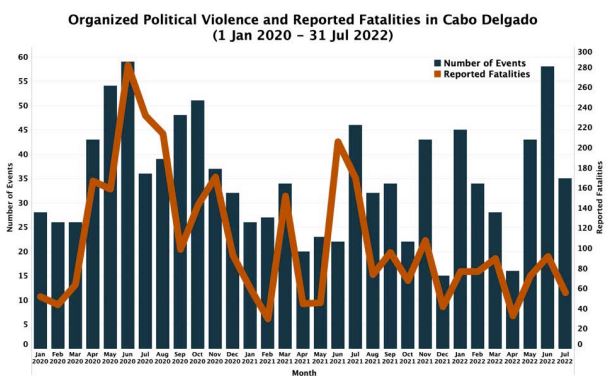

Back on August 16, the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project’s (ACLED) Mozambique conflict observatory, Cabo Ligado (“connected cape”) issued their most recent summary of the violence that has taken place in the country since October of 2017. The weekly report noted that recent events had brought the total number of organized political violence events to 1,382 with the total number of fatalities from organized political violence reaching a disheartening 4,188. Furthermore, the total number of reported fatalities from organized violence directly targeting civilians has reached 1,818, with attacks on civilians and their property reported recently in Muidumbe district.

In response, Mozambican President Filipe Nyusi, in an August 8 address to the National Youth Conference, stated that the armed violence in Cabo Delgado province is tantamount, “to a new form of colonialism,” arguing that extremist groups in the area, “manipulate the conscience of young people, with the aim of plundering the existing resources in the territory and perpetuating the suffering and poverty of Mozambicans.” Relatedly, on August 17, the Southern Africa Development Community renewed the deployment of the Southern African Development Community Mission in Mozambique (SAMIM) for twelve more months, in an attempt to continue to contain the violence.

However, while the militarized response to the insurgency and unrest in Cabo Delgado province has managed to tamp down on the violence and improve the overall security conditions in the region, issues still remain. For instance, there still exists the problem that, despite SAMIM forces driving away, degrading, and demoralizing the insurgents from Cabo Delgado—as the United States Institute of Peace’s (USIP) Andrew Cheatham, Amanda Long, and Thomas P. Sheehy recently put it—local civilians still do not trust the local government and police forces, with one Mozambican civil society representative telling USIP in June that the government, “only care[s] about protecting the interests of big companies.”

Despite the relative success of the multinational intervention’s troop presence—which includes more than 3,000 troops from the Southern African Development Community’s Angola, Botswana, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Lesotho, Malawi, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia as well as Rwanda—and the recent downgrading of the Mission from “An African Union Policy Guideline on the Role of the African Standby Force in Humanitarian Action and Natural Disaster Support” Scenario Six (AU interventions in grave circumstances such as genocide) to Scenario Five (AU Peace Support Operations for Complex Multidimensional Operations), stabilization operations are just the first step required to address the needs of the citizens of northern Mozambique. If Maputo—as well as its international partners—wish to address the more than one million internally displaced persons in the country as well as the similar number of Mozambicans facing severe hunger, the government will not only need to show a commitment to address the tricky security situation on the ground, but it must also show that it is willing and able to address the root causes of the ongoing humanitarian crisis. However, when figuring out the exact causes of the violent extremism plaguing the country, one must be careful to not to overcomplicate the analysis to too great a degree. While some say that “a complex mix of history, ethnicity, and religion, and the war has been fuelled by poverty, growing inequality, and the ‘resource curse’,” as was argued in August of 2021 by the London School of Economics’ Dr. Joseph Hanlon, others see differing explanations.

In looking at the roots of the crisis, one recent attempt to explain the drivers of the insurgency in northern Mozambique is an August 2022 report from Martin Ewi, Liesl Louw-Vaudran, Willem Els, Richard Chelin, Yussuf Adam and Elisa Samuel Boerekamp of the Institute for Security Studies (ISS), “Violent extremism in Mozambique: Drivers and links to transnational organised crime,” which argues that the usual suspects of, “historic disenfranchisement, poverty, marginalisation, endemic corruption and political exclusion,” are not enough to explain the exact roots of the conflict in Cabo Delgado, and that it instead, the legacy of the country’s independence and civil wars, “left behind a war industry that has nourished terrorism and other forms of violence.”

Roots of the Insurgency

For the ISS authors, the recurrent political conflict between the ruling Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO) and the opposition Mozambican National Resistance Movement (RENAMO) has created a vulnerable society where political grievances often explode into violence. Furthermore, as the London School of Economics’ Joseph Hanlon has pointed out in a May 23 article for BBC News, while, “both the U.S. and [Islamic State] want this to be seen not as a local civil war, but as a clash between two global powers,” there is the fact that, “most Mozambican researchers say local issues remain dominant.” As such, the ISS report authors argue that the insurgency is not just another stage for the international clash between the West and the international jihadist movement but instead came about just as, “Mozambique was beginning to entrench democracy, but also when the disparity between the rich and the poor was becoming a serious concern.”

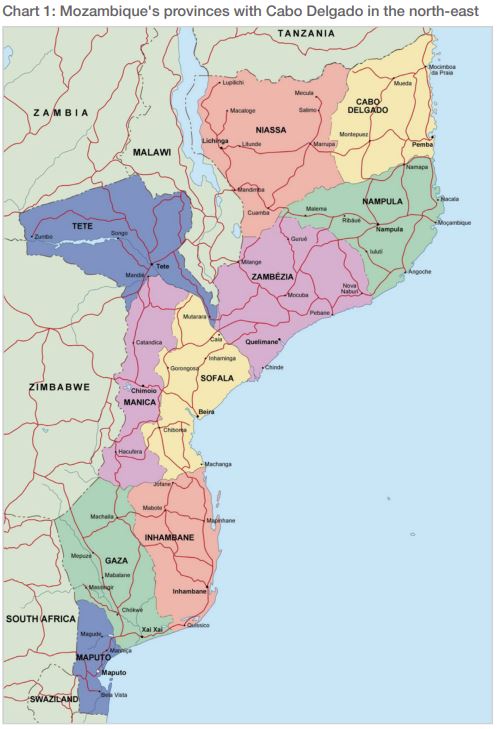

Furthermore, as Hanlon notes in his August 2021 piece, “Ignoring the Roots of Mozambique’s War in a Push for Military Victory,” the conflict is not only a, “new civil war” but it is, “taking place in the same areas where the 1964-1974 independence war began,” with striking similarities between the resource- and wealth distribution-related conflict of the 1960s and 1970s and the violence taking place today. For Hanlon, the issues preceding the independence war were that, “colonial authorities were seen to be taking the wealth of the area and leaving nothing behind,” whereas, “FRELIMO is now the government, and people along the coast see themselves as marginalised by a FRELIMO elite,” especially as, “the post-2000 resource boom, driven by rubies, graphite and natural gas lead to increased poverty and sharply increased inequality.” Whereas In the 1960s, it was Portuguese oligarchs siphoning off the people’s wealth, today, it can be argued that the FRELIMO government has seen its own elites enrich themselves at the expense of the average northern Mozambican.

As Penn State University’s Dennis Jett argues in a March 2020 piece for Foreign Policy, the FRELIMO government has been corrupt, and, since 1975 has, “succeeded in abusing their power because of the lack of the countervailing forces such as an independent legislature and judiciary, a free press, and a strong civil society sector.” Furthermore, Jett argues, “these rulers have been aided by the complicity of some countries, energy companies such as ExxonMobil, and aid organizations such as the U.N. Development Program and the Millennium Challenge Corporation, and the indifference of others.”

However, the government’s inattention towards its citizens has not been equal, with a distinct geographic element at play between northern and southern Mozambique that renders the conflict all the more complicated. Specifically, as was noted in a June 2021 report from the International Crisis Group, senior FRELIMO officials have acknowledged that following the independence war, the FRELIMO government, “ paid a lot of attention to the development of the regions of the south and the central part of the country where the war with Renamo took place, but in so doing we also have to take the blame for having neglected Cabo Delgado.”

Because of that inattention, Cabo Delgado has remained one of Mozambique’s poorest regions, even before the outbreak of the 2017 insurgency, with, “high levels of poverty and [an] absence of services,” as well as widespread illiteracy. As a result, locals in Cabo Delgado list poverty and lack of education as some of the main causes underlying the formation of jihadist group Ahlu-Sunnah wal Jama’ah (ASWJ)—also known locally as al-Shabaab, ISIS-Mozambique, or Mashabab—and locals exhibit a, “strong evidence of resentment against elites who are believed to be benefitting from the province’s resources, while the rest of the people of Cabo Delgado languish in poverty and without basic services.”

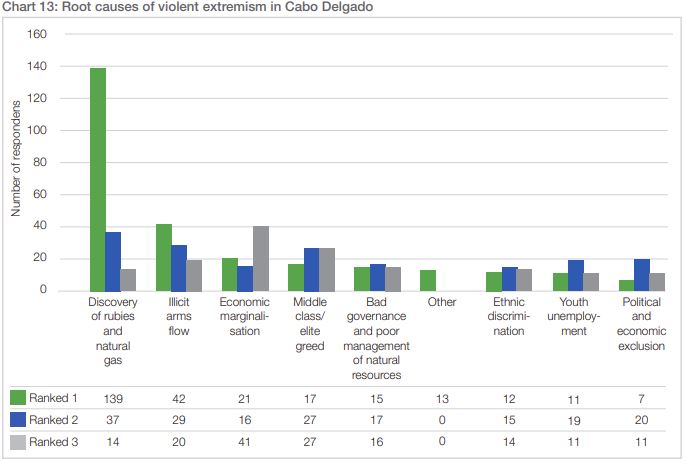

Similarly, a large number of Cabo Delgado residents see the unequal distribution of natural resources, and their resultant revenue streams, as the root cause of the conflict, with 139 of the 309 respondents interviewed by ISS rating the 2010 discovery of natural gas in the Rovuma Basin off the northern coast of Mozambique as the root of the conflict, followed by, “illicit arms flows (42), economic marginalisation (21), middle class/elite greed (17) and poor management of natural resources (15).”

Specifically, the early 2000s discovery of rubies and gold in Cabo Delgado—which has seen the province become one of the world’s most productive sources for gem-quality rubies—led to thousands beginning to work a large deposit near the city of Montepuez, most without proper permits, with the Maputo government deciding in 2009 that unlicensed mining would be tolerated. This permissive attitude led to the influx of tens of thousands of artisanal miners to the area, though the main concessions are administered by Gemfields—the world’s leading supplier of rare colored gemstones—and its seventy-five percent owned subsidiary Montepuez Ruby Mining (MRM), which has relied on the regionally controlled Protection Police and Maputo’s Rapid Intervention Force (FIR) to protect its concessions from encroachment by such artisanal miners.

Furthermore, the main ruby mine was originally controlled by FRELIMO-linked oligarch Raimundo Pachinuapa, who allegedly, “used his position to seize the land where the mine is located, drove out thousands of people and entrusted Gemfields with 75% of the company on the condition that he did nothing and kept 25% of the money raised,” according to a 2021 interview with the LSE’s Joseph Hanlon. Furthermore, the director of Gemfields in Mozambique is the son of former Mozambican President Samora Machel, Samora Machel Jr., raising a number of corruption-related questions.

Even more concerningly, the Protection Police and Maputo’s Rapid Intervention Force have been accused of human rights abuses against locals and artisanal miners, with Mozambican investigative journalist Estacio Valoi writing for Foreign Policy in 2016 that, “the violence in Montepuez is intertwined with the government’s expansion of industrial areas that has seen locals forcibly removed from their homes,” noting that, in September 2014, FIR operatives, “burned down some 300 houses in the market villages of Namucho and Ntoro, in the Namanhumbir region of Montepuez, and beat residents, according to interviews with the village chief, local residents, and artisanal miners,” with a similar incident occurring in September 2012 as well. This violence towards civilians can only lead to further resentment between the locals and Maputo. As was said by one local villager, “they took our lands and burned our houses…Now they even want us out of our villages, to abandon our traditions and go to places where there is no water and the land is not good for agriculture. We will not leave, even if they kill us here.”

Moreover, the discovery of natural gas in 2010 led the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies’ Anne Frühauf to note in 2014 that, “the resource boom is drastically raising public expectations,” and that, “dashed expectations could fuel worse social tensions in future years, unless [former Mozambican President] Guebuza and his successor get serious about putting in place comprehensive policy responses – in terms of monetary, macroeconomic, and broader structural policy reforms that cater to the inclusive growth agenda.”

However, such reforms never took place, and, as João Feijó, a researcher at the Rural Environment Observatory (OMR) in Mozambique told the Telegraph in July of 2021, as a result, “local youth felt unprotected by the government because there were thousands of…Mozambicans from the south and foreigners that were arriving and getting the best jobs,” and that locals felt that, “they didn’t have the opportunities for education so they could not compete.” As was remarked on in the ISS report, while, “assurances were made that local inhabitants would benefit first from LNG projects and that those displaced would be compensated…perceptions have been of the contrary and many see natural gas and its promises of prosperity as aggravating inequality and resentment against those in government who would benefit from the projects.”

Political Strife and Corruption

Further complicating the situation in Cabo Delgado is Mozambique’s ongoing political strife, which has existed in some form since just after independence. As the ISS report asserts, violence and boycotts characterized the country’s post-civil war elections in 1994, 1999, 2004, 2009, 2014 and 2019; and though a demobilization, disarmament, and reintegration (DDR) process has been agreed on between the government and RENAMO, the FRELIMO governments fear of the former rebels has caused Maputo to be reluctant to use the military as a first responder to the situation in Cabo Delgado, possibly missing out on the best chance to end the insurgency in its infancy.

Furthermore, despite RENAMO’s participation in the DDR process, the FRELIMO government has yet to live up to its commitments towards decentralization. Furthermore, as has been observed by the Chr. Michelsen Institute’s (CHI) U4 Anti-Corruption Center (U4), President Nyusi’s FRELIMO party has been accused of engaging in electoral fraud, with, “the general election of October 2019…marred by serious irregularities,” which saw, “President Nyusi re-elected with 73% of the vote and Frelimo winning in all provinces, allowing them to appoint all provincial governors,” despite EU Election Observation Reports and international NGO Freedom House detailing various accounts of ballot-box stuffing and other forms of fraud.

Taken together, the ISS authors argue, the political context in Mozambique is one that shows the conditions conducive to the spread of terrorism, as corruption and the avarice of state actors are some of the key factors that allow for violent extremist organizations to emerge and thrive. As a result, the majority (54.03%) of those interviewed by the Institute for Security Studies authors described the situation in Cabo Delgado as terrorism, with another 20% referring to it as an insurgency. Furthermore, a majority of respondents named ASWJ or Al-Shabaab as the main party responsible for attacks on locals, with the formation of the group attributed to various factors including greed, poor governance, and other grievances.

ASWJ’s Modus Operandi, Ideology, and Recruitment

As was pointed out in the ISS report, “the approach by ASWJ in Mozambique resembles that of other terrorist groups, such as Boko Haram’s beheading of captured religious leaders and soldiers,” with group members initially targeting police, soldiers, and local councilors, but eventually becoming more indiscriminate in their attacks. Furthermore, while the group does not possess a signature attack style, the group is, “known to [use] ISIS methods such as beheading, torture tactics, kidnapping and melestyle attacks.”

The group, as has been noted by Queen’s University’s Eric Morier-Genoud, “is old, and started in 2007 as an Islamist sect that wanted to have a Muslim government.” When that did not work out, and fueled by a combination of the social and economic grievances listed above, the group, “they switched to an armed ‘jihad’ movement,” in 2015, two years before launching its first attack on Mocimboa da Praia in October 2017, and four years before pledging the group’s allegiance to the Islamic State.

In terms of the group’s overall ideology, while Amal El Ouassif and Seleman Yusuph Kitenge of the Policy Center for the New South feel that, “the origins and ideological underpinnings of the movement called Al Shabaab or Ahl Al Sunna Wa-Al Jamâa are unclear,” the ISS authors argue that local Cabo Delgado residents stated that they believed that the group’s ideology was rooted in exploiting the natural resources of the province, failure of governance in the region, and facilitating the rise of illicit trade and organized crime.

When it comes to Mozambican’s religious beliefs and ethnicity, both the ISS’ and the Policy Center for the New South’s authors agree that, “religion plays a central role in the region,” with the Christian, FRELIMO-linked, Makondé wearing rosaries around their necks, while the mainly-Muslim Mwani men go out publicly with prayer hats and women wearing hijabs. However, Ouassif and Kitenge are careful to note that linking the insurgency, “solely to religious radicalism would be very simplistic.” That being said, over 60% of those interviewed by the ISS authors cited religion as playing a role in ASWJ’s ideology, indicating that the group not only is—but is viewed as being—composed of religious extremists. Indeed, anthropologist Carmeliza Rosário, working on a research project for Chr. Michelsen Institute points out that, “the insurgents are not targeting Christians more than Muslims, but rather the opposite, attacking those who do not practise their version of Islam.”

As Eric Morier-Genoud writes in a July 2020 paper for the Journal of Eastern African Studies, “The jihadi insurgency in Mozambique: origins, nature and beginning,” the insurgency likely began life in the district of Balama in 2007 when a Makura man named Sualehe Rafayel returned to his village after several years in Tanzania and joined a local Wahhabi mosque built by the Kuwait-linked Africa Muslim Agency. When Rafayel tried to convert members of the mosque to the more strict version of the Islamic faith that he now followed, tensions rose between himself and other local Muslims, causing Sualehe to withdraw from the mosque to his own religious building in his personal compound. Ultimately, Sheikh Sualehe and the local community continued to clash over his opposition to formal education, praying in the mosque wearing shoes, and praying just three times per day. Over time, the group—whether it was called Al-Shabaab, Al-Sunnah Wal-Jamaa, or Swahili Sunnah—began constructing its own mosques and distanced itself from both state institutions and the wider Islamic society. However, it also began engaging in proselytizing as well as offering financial loans to micro-entrepreneurs and educational opportunities to the local populace, a popular move that built up the group’s opinion with the youth in the area.

It took a period of ten years for the group to eventually turn violent, with Morier-Genoud arguing that the shift likely occurred, “as a consequence of the repression it experienced from the mainstream Muslim organizations, and, later on, the state – the latter’s involvement possibly tipping the sect into abandoning its approach of withdrawing from society.” Indeed, in early October 2017, community leaders in Mocimboa da Praia issued a complaint to the local authorities—about the group conducting mobilization activities and spreading propaganda on the mandatory use of the burqa by all Muslim women—which proceeded to arrest nearly thirty members of the group. On October 5, the remaining members of the Al-Shabaab raided the prison and three Mocimboa police stations, kicking off a cycle of violence that would continue until today.

As the ISS authors write, however, while those Mozambicans interviewed did note that ASWJ declared in the beginning that its motives were religious, the group has changed their desires to reflect a goal of overthrowing the government. Moreover, while 81.2% of respondents believed that mosques and Islamic centers were the primary vehicles for radicalization, the youth that are selected for recruitment are not targeted through an appeal to religious motivations, but rather to their pecuniary interests. Specifically, the ISS report notes that respondents pointed to ASWJ leaders offering young people, “ big sums of money ranging from MT100,000 (US$1,500) to MT500,000 (US$7,700),” and that, faced with few other chances for a livelihood, the youth often accept. However, the ISS authors also allow that, often, “ASWJ recruitment strategies are perceived to be situation/context dependent as ‘some are taken forcibly, while others are enticed and funded…” though now the group is less likely to make use of monetary and employment promises, instead proceeding to burn houses and take the people and things that it desires.

ASWJ, Terrorism, and Organized Crime

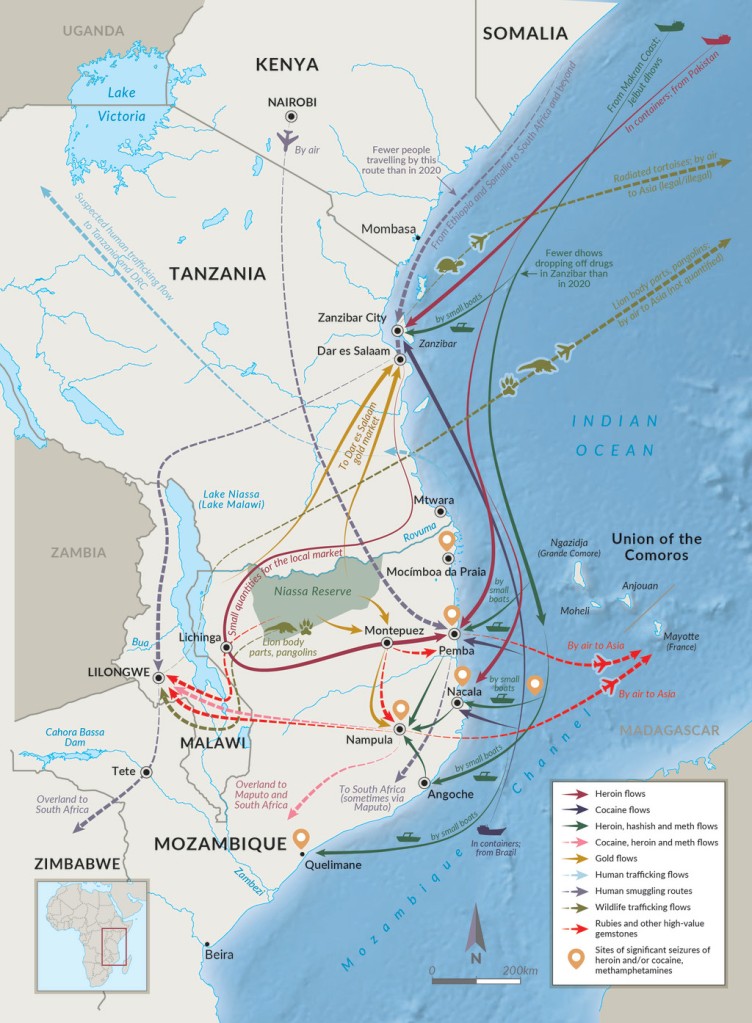

Where the ISS authors depart from other analyses of the situation—and what they somewhat fail to convincingly argue—is that, in Cabo Delgado, there exists a nexus between the insurgency and organized crime linking the ongoing violence with the smuggling and trafficking of various illicit commodities. The ISS authors point to a 2018 article by Hanlon which argues that after the 2012 killing of Al-Shabaab-linked cleric Aboud Rogo Mohammed in Kenya, his followers came under pressure by security forces there and moved south into Cabo Delgado. Once there, the group became involved with local smuggling barons and used, “incomes made from smuggling, religious networks, and people-traffickers,” to pay to send young men to Kenya, Somalia, and Tanzania for military and Islamic training. Furthermore, while a Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime study found no evidence that ASWJ controls the illicit economy, its members may be involved in some illegal schemes.

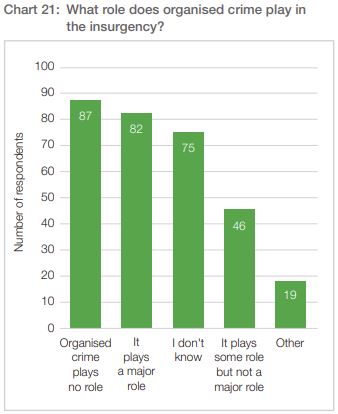

However, the ISS report does acknowledge that, “the available open source evidence supporting claims that the insurgents are being financed by drug trafficking, fauna crimes, illegal artisanal mining and other organised crime acts, is weak,” though they argue that it may be a question of missing evidence, as they find it hard to believe that a criminal group can set itself up in the heart of a major organized crime environment, but not be a part of that system. Furthermore, the ISS report points to the responses from interviewees, 51% of whom perceived the insurgents as having a direct involvement in organized crime.

A major part of this organized crime nexus is the heroin trade, which, as Hanlon writes in a July 2018 paper, “The Uberization of Mozambique’s heroin trade,” has seen Mozambique become a “significant heroin transit centre” where the trade, “has increased to 40 tonnes or more per year, making it a major export which contributes up to $100 mn per year to the local economy,” and, “has been controlled by a few local trading families and tightly regulated by senior officials of Frelimo, the ruling party, and has been largely ignored by the international community which wanted to see Mozambique as a model pupil.”

Another criminal racket that ASWJ has been linked to is kidnapping for ransom, with Human Rights Watch stating that the group has, since 2018, kidnapped more than 600 women and girls, forcing, “younger, healthy-looking, and lighter-skinned women and girls in their custody to “marry” their fighters, who enslave and sexually abuse them,” while, “others have been sold to foreign fighters for between 40,000 and 120,000 Meticais (US$600 to US$1,800).” Furthermore, the group also, “abducted foreign women and girls, in particular, [who] have been released after their families paid ransom.” Moreover, the group has also engaged in arms trafficking, not only seizing weapons in raids on Mozambican security forces, but bringing in weapons from Tanzania, the DRC, Kenya, and Somalia as well.

Finally, there are ASWJ’s links to illegal mining, as pointed out by Saide Habibe, Salvador Forquilha and João Pereira of the Institute for Social and Economic Studies (IESE) in Mozambique, who argued in a 2019 report that, “as in other countries facing violent extremism, funding for the Al-Shabaab group in Mocímboa da Praia and the surrounding districts (at least in the early stages) came from an illicit local economy with links to clandestine networks trafficking in timber, charcoal, rubies and ivory, among other products.” Habibe, Forquilha, and Pereira state that Al-Shabaab was linked to the mining and sale of rubies, as, “groups of illegal prospectors from Somalia, Ethiopia, Tanzania and the Great Lakes region have settled in the Montepuez region and established alliances with local religious leaders via marriage ties.”

For the ISS authors, “the nexus with illegal mining is, therefore, by appropriation as the group has appropriated what is largely an organised crime strategy,” though they acknowledge that, “more research is needed to determine the full scale of ASWJ’s sources of funding.” However, the authors do point to the fact that some reports have emerged about South Africans financing terrorist groups in Mozambique, with the U.S. Treasury Department in March 2022 blacklisting Farhad Hoomer and Sirraj Miller of South Africa for being, “‘South Africa-based ISIS organizers and financial facilitators,” of ISIS-Mozambique/ASWJ, with the Treasury press release stating that, “ISIS branches in Africa rely on local fundraising schemes such as theft, extortion of local populations, and kidnapping for ransom, as well as financial support from the ISIS hierarchy,” which would seem to indicate some links between organized crime and the insurgents.

However, the ISS report does note that the, “reported increase in the volume of trafficking and smuggling in Cabo Delgado and adjoining regions since the conflict began suggests that the traffickers and smugglers are benefitting from the insurgency,” which denotes a more symbiotic nexus between the two groups rather than organized crime being the proximate cause of the insurgency.

Maputo’s Response

The ISS report notes that the response from the state has been mainly securitized, with the government initially labeling the insurgents as “malfaitores”, criminals or evildoers who needed to be handled by the police. However, following the October 5, 2017 attacks on Mocimboa da Praia, the government took a more militaristic turn, first bringing in the Russian private military company Wagner Group and then later replacing them with South African Dyck Advisory Group when Wagner failed to overcome their own poor understanding of the operating environment. However, Dyck Advisory Group also failed to achieve success against the insurgency, despite having carried out indiscriminate attacks on civilians, as well as extrajudicial killings, as has been alleged by Amnesty International.

Ultimately, the mercenaries were replaced by the Mozambican military, along with a deployment of Rwandan and SAMIM forces in 2021. The ISS authors note that despite the abuses of the mercenaries, and the unpopularity of military interventions against Boko Haram in Nigeria and al-Shabaab in Somalia, nearly ⅔ of Mozambican respondents believed that the militaries had been effective in curtailing insurgent attacks, with the SAMIM forces gains including, “retaking control of all formerly terrorist-controlled towns, including Mocimboa da Praia, Quissanga, Macomia and Nangade, the neutralisation of several key terrorist commanders, and the dismantling and destruction of their bases,” rendering ASWJ significantly smaller and weaker, though still deadly.

ISS Recommendations

The ISS report closes with a number of recommendations for the government of Mozambique, its neighbors, the SADC, the AU, and Mozambique’s international partners. For Maputo, the ISS authors propose that it enact measures to empower communities to take ownership of their own security and become partners of the state for intelligence and early warning against jihadist attacks. They argue that the government needs to not only listen to the grievances that people have regarding unemployment and ethnic discrimination, but it must do so while identifying particular roles for the youth, women, private sector, academia, and civil society in making decisions for their communities.

Ultimately, the authors contend that the state needs a comprehensive national strategy that addresses the political, humanitarian, socio-economic, and security aspects of the insurgency’s origins, as well as plans to address the perennial lack of livelihoods in Cabo Delgado. Furthermore, they state that the government needs to: set up pro-poor and pro-youth development projects that address regional inequalities; equip the criminal justice system to bring to justice all those suspected of participating in the violence; set up a national commission to investigate the root causes of extremism in Cabo Delgado; strengthen cooperation with neighbors on intelligence sharing regarding the movement and activities of both extremists and organize crime groups; and institute a zero-tolerance policy for corruption, enhancing the country’s intelligence services to detect the sources, routes, and enablers of organized crime in Cabo Delgado.

For Tanzania and Mozambique’s other neighbors, such as Uganda, the authors argue that those states should help Mozambique tighten security at its borders, regularly share intelligence, and urge border communities to not host any person suspected of terrorism.

With regard to the Southern African Development Community, the authors state that the organization must strengthen coordination among troop contributing nations to combat the insurgency, inviting Rwanda and Uganda to any SADC meetings that discuss the situation in Cabo Delgado. Furthermore, the authors encourage the SADC to create a taskforce to study the origins and motivations of the insurgency, drawing lessons for how to prevent the emergence of such groups in neighboring countries. In addition, they propose that the SADC do more to enforce its existing instruments, including the SADC Counter-Terrorism Strategy and the SADC Transnational Organized Crime Strategy and Implementation Action Plan; mobilize its neighbors to strengthen cooperation on border security; and appeal to the international community for more funds to fight terrorism in Mozambique.

For the African Union, the authors propose supporting the SADC by considering implementing AU Scenario Six on the use of the African Standby Force if the SADC requests the AU take over the situation in Cabo Delgado. In addition, they: encourage the AU’s Peace and Security Council to regularly review the situation and adopt a decision on Cabo Delgado; encourage greater collaboration between SAMIM, Rwandan, and Mozambican forces; and advocate for the AU Commission to support and assist the SADC in sourcing funds for SAMIM forces, providing them with the capabilities to conduct air combat and night missions.

Finally, for the EU, UN, and the rest of the international community, the authors propose that they do more to strengthen Mozambique’s ability to investigate and prosecute terrorist acts. They also argue that UN aid agencies should increase the supply of food and other aid to IDPs in Cabo Delgado; and that Mozambique’s international development partners support a military presence in Mozambique. In addition, they propose that, similar to the successful amnesty program for Niger Delta militants, Mozambique’s European partners should, “offer an option for militants who are ready to lay down their arms to undergo their DDR programme in European countries and their final reintegration in Mozambique.”

Better Explanations for the Insurgency

However, despite the ISS reports title, the authors do not make a completely convincing case for ASWJ’s creation being caused by the presence of organized crime in northern Mozambique. While the authors do clearly show the presence of an extended network of criminal activity in the area, the report does not do enough to link those networks with the beginnings of the insurgency. Furthermore, the report’s conclusion regarding organized crime seemingly ignores some better explanations that are offered already in the analysis.

For instance, as the ISS authors note, the first iteration of a radical Islamist sect in Negande with a doctrine and dress code similar to modern day Mozambique’s Al-Shabaab/ASWJ existed back in 1989, before the influx of artisanal gold miners to Cabo Delgado in the early 2000s. Moreover, Liazzat Bonate of the Chr. Michelsen Institute argues that Salafi-Wahhabis ideologies have a long history in Mozambique, dating back at least to the 1950s and 1960s, though their presence had not led to an insurgency.

Bonate argues that it was not until the late 1990s, when Mozambican Muslims—returning from scholarships at known centers for Wahhabism and Salafism such as the Universities of Medina in Saudi Arabia and Al-Merkaz Al-Islami in Sudan—founded a movement called Ahl al-Sunna or Ansar al-Sunna, building mosques and madrassas, and providing locals with an Islamist ideology and a sense of dissatisfaction with the socio-political context of northern Mozambique.

As Bonate asks, as Mozambicans did not manifest jihadism before 2017, the question is, “why in 2017 and why in Cabo Delgado?” For Bonate, it is the, “existence of a favorable and fertile environment for jihadism to penetrate and expand,” as, “the exclusionary practices of political and economic governance of local or central institutions of the State, ethnic tensions, marginalization, bad administration, corruption, police violence, tensions between center and periphery etc. fertilize the soil for jihadism to flourish.”

Therefore, instead of focusing on the links the insurgency has to transnational and organized crime, one would do better to focus on the other issues that create a welcoming environment for violent extremism to take root. As Emilia Coloumbo, senior associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ (CSIS) Africa Program wrote recently in a piece for the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), Mozambique has a number of sources of instability that create fertile ground for extremists to operate. These include a limited political space for countervailing forces due to the dominance of FRELIMO since independence in 1975; stalled implementation of 2018’s constitutional reforms that were intended to create space for opposition parties; endemic corruption; a hidden debt scandal which may have cost Mozambique at least $11 billion and pushed nearly two million people into poverty; economic inequality exacerbated by FRELIMO’s political dominance; and an overall tense relationship between the state and its citizens due to this limited political space, corruption, a lack of electoral integrity, and the resultant economic pressures on ordinary Mozambicans.

As ASWJ likely began its recruitment efforts by originally offering poor and unemployed youth loans that they could invest in order to help them build wealth, it is difficult to argue that the underlying socio-economic conditions in northern Mozambique created a fertile ground for the insurgency and its subsequent criminal activities, rather than the criminal activities leading the group into jihadism. Furthermore, as Columbo notes in her piece for the CFR, ASWJ’s “limited public statements have focused on criticizing the government for corruption and using the hard work of the Muslim poor for self-enrichment.”

Furthermore, one simply has to look at how Cabo Delgado has fared socio-economically to see how the local youth might be easy prey for extremist groups. As was pointed out in a 2020 report by Dorina A. Bekoe, Stephanie M. Burchard, and Sarah A. Daly for the Institute for Defense Analyses, “Cabo Delgado is certainly poor. It is the lowest ranked Mozambican province in terms of income, human development, and education,” despite its relative wealth of natural resources.

In the end, one simply cannot ignore the fact that not only has Cabo Delgado been largely ignored by Maputo and the FRELIMO government since independence, but since the discovery of rubies in the early parts of the 2000s, not only have locals not seen a tremendous benefit but, “Mozambicans living in the area of the mines have been relocated, sometimes forcibly and extrajudicially.” Furthermore, despite Gemfields’ protestations otherwise, “local miners reported being harassed, beaten, and shot by gangs affiliated with the security forces assigned to protect the [ruby mining] concessions.”

A better explanation for the explosion of violence in Cabo Delgado in 2017 would likely be the discovery of oil and natural gas off of the coast in 2011, which, combined with the abuse towards artisanal miners beginning in 2012, may have been the final slight that ASWJ needed to tip it over into a full-scale insurgency; especially as the group felt that the Maputo government would, once again, be taking the lion’s share of the wealth, leaving little for northern Mozambicans.

While organized crime likely plays a role in providing the insurgents with the money and arms that they need to carry out their attacks, it is not likely that the simple presence or even prevalence of organized transnational crime would have been the proximate cause of ASWJ’s shift from advocating for a Muslim government to full-scale assaults on the local populace. Unfortunately, in Mozambique—with its history of elite patronage, favoritism towards Christian Makondés, and rampant corruption—the traditional seeds for an insurgency were already present, with the government having failed for over forty years, from independence to the beginning of the attacks, to address the underlying grievances of those living in northern Mozambique.

Attempting to Bring an End to the Conflict

Unfortunately, the militarized response to the insurgency has not achieved all of the results that its implementers may have desired. For instance, Cabo Ligado’s most recent monthly update for July 2022 notes that, despite some successes from some SAMIM special forces units and the establishment of a major SAMIM base north of Macomia, “SAMIM’s capacity for offensive patrols in the dense forests of Cabo Delgado remains limited.” Furthermore, the same report argues that, “notwithstanding positive developments in some parts of the province, there are deep concerns the insurgency may spread further and that insurgents are training new recruits and may be developing new bases, and logistical and supply networks in neighboring provinces,” and that, “SAMIM is already overstretched and is ill-equipped to take on other areas.”

Ultimately, even Maputo realizes that a predominantly militarized response will not be enough to end the conflict, with Mozambican Minister of National Defense Cristóvão Artur Chume telling the International Crisis Group earlier this year that, “we need more than just weapons to end this conflict, something more than military operations.” Furthermore, as another government advisor told the Crisis Group, “…what the youth who are fighting really want is a sense of social justice and a permanent stake in the future of Cabo Delgado.”

As such, any resolution to the conflict will have to begin with an acknowledgement from Maputo that FRELIMO government elites cannot continue business as usual if they wish to see peace in the country. Government authorities will not only have to engage in dialogue with the insurgents, but they will have to be ready to meet some of their demands for a more equitable allocation of the resource rents in the northern parts of the country.

However, where the Institute for Security Studies authors are correct is that the issue of organized crime will also have to be addressed if the insurgency is to be dismantled. While the role played by organized crime in the genesis of ASWJ is debatable, its role in the sustenance of the organization is undeniable, as drug, gem, and timber smuggling, as well as human trafficking, are a major source of ASWJ’s day-to-day funding. As part of that effort, Maputo will need to enlist aid not only from its neighbors, but the AU, UN, European Union, and the United States, as they aim to combat illicit trade and organized crime in the region.

In the final analysis, any discussions of the role of religion, ethnicity, or organized crime in the insurgency must grapple with the key fact that, as the Chr. Michelsen Institute’s Carmeliza Rosário told the Nordic Africa Institute back in April, while religion and ethnicity partly explain the outbreak of conflict, those issues don’t take into account the fact that, “the state has for a long time been very repressive and violent towards its citizens – especially in Cabo Delgado and the other provinces in the north. Years of unfair treatment by government officials have made people view the state if not as an enemy, then at best as someone who doesn’t care about their wellbeing.” When coupled with the ongoing corruption in the country, including the hidden debt scandal and the removal of artisanal miners from sites now run by international gemstone mining giant Gemstones, Rosario states that, “all this combined creates frustration and desperation, and also a sense that the state is not helping me but working against me. Radicalised and violent young people are not uncommon in the world. But building a movement that actually threatens the state can only happen where the social contract is weak.”

In the 1940s, an American medical researcher at the University of Maryland named Theodore E. Woodward was credited with coining a rather apt aphorism for the situation in Mozambique: “When you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras.” While organized crime networks certainly exacerbate the problems caused by ethnic and religious conflict in the region, the best explanation for the insurgency plaguing northern Mozambique is actually the broken social contract between the Mozambican people and the FRELIMO government.

Only efforts to repair that contract—whether through a more equitable allocation of resource rents to the northern parts of the country; communicating more and better with locals; a stronger commitment to fight corruption; efforts to bring local civil society and community leaders into district and provincial governance; attempts to professionalize the security services; and better efforts to return state services to Cabo Delgado and develop the region—will be able to begin to end the cycle of violence. However, Maputo will have to realize that with the trust between the government and the people of Cabo Delgado having been frayed so badly, it is the FRELIMO-led government that will have to first communicate a strong commitment to reversing four decades of neglect.

Unfortunately, all signs are that the FRELIMO-led government has not internalized the fact that the conflict is likely caused by local grievances, with the Mozambican Council of Ministers having earlier this year failed to approve the multilateral Northern Resilience and Integrated Development Strategy (ERDIN), which would budget $2.5 billion for three pillars, including: “Support for peace building, security and social cohesion”; “Reconstruction of the social contract between the state and the population”; and “Economic recovery and resilience.”

As Joseph Hanlon wrote in his August 2022 Mozambique News Reports & Clippings, “the [ERDIN] proposal put substantial emphasis on local grievances – poverty, inequality, marginalisation, and no gains from local resources – as one of the major roots of the current civil war,” however, “President Filipe Nyusi has always rejected this, and government refused to even submit the ERDIN to the Council of Ministers, leading to a stand-off,” whereafter the EU, African Development Bank, World Bank, and United Nations Development Programme backed down, with the Council of Ministers approving on June 21, “a new version of the document which dropped almost all references to poverty, inequality, and grievances.”

For Hanlon, the surrender from Maputo’s international partners is partly due to the fact that, “gas and minerals and the potential for huge contracts led the international community to throw their full backing behind Frelimo as people they could deal with.” Despite a 2019 EU election observation mission report claiming that Mozambique’s, “ elections commission did not follow the law, the voters register was inflated, ‘an unlevel playing field was evident throughout the campaign’ with violence and illegal limitations on the opposition, and a wide range of irregularities,” the head of the EU Electoral Mission, Nacho Sánchez Amor—despite telling the press that changes were “absolutely imperative” and that, “if there is the political will, it can be done”—merely conveyed to the Mozambican Foreign Minister that, “it would be nice” if some of the reforms suggested could be implemented.

For Hanlon, as a result of Sánchez Amor’s statement, “the message was loud and clear: the EU will allow Frelimo to steal the next elections.” As such, it is highly unlikely that, absent external pressure, the Nyusi government will recognize the impact of local grievances on the conflict. Until it does so, the international community will have no real partner in Maputo, and the insurgency will continue to have no end in sight.