December 2, 2022

Back on March 24th, a month after the Russian invasion of Ukraine began, Chinese state media service Xinhua News Agency published an article blasting the Western-centric behavior of the United States, proclaiming that, “double standards were boldly on display when the U.S. urged European countries to absorb people fleeing Ukraine while [remaining] indifferent to refugees from certain war-torn places in the Middle East and parts of Asia, whose suffering has stemmed mainly from years-long, hegemony-sustaining military operations led by the United States.”

Simultaneously, in Africa, “a lack of imagination and creativity, and overreliance on European former colonial powers, has stymied the emergence of the type of policy that fosters mutually beneficial partnerships with African countries.” This has led to a situation where, “the United States has struggled to clearly define its strategic interests beyond an obsession with short-term stability that props up unpopular political regimes at the expense of the populations,” with U.S. support for a string of undemocratic leaders in Chad, Gabon, and Cameroon fueling, “instability in the long run and [undermining] U.S. support for democratization efforts in countries such as Zambia and Malawi, which have registered impressive democratic gains, and Zimbabwe, which is grappling with a repressive regime.” Meanwhile, Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari alleged earlier last month that, “many of my peers are frustrated with Western hypocrisy and its inability to take responsibility” when it comes to the impact of climate change on Africa.

As the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Catherine Nzuki and Mvemba Phezo Dizolele have argued, “the status quo of the U.S. approach to Africa—poorly articulated and at times heavy-handed and paternalistic—has left the United States flat-footed at a time of intensifying geopolitical contestation and more assertive African leaders,” as, “China continues to deepen its strong economic and political ties throughout Africa [and] Russian influence and paramilitary activities expand across the continent.” This has left, “the United States, once reliably the major foreign player on the continent”, adrift in a, “crowded field vying for influence.”

While the White House’s “U.S. Strategy Toward Sub-Saharan Africa”, released late this summer, acknowledges that, “it is impossible to meet this era’s defining challenges without African contributions and leadership,” and thus attempts to articulate, “a new vision for how and with whom we engage,” in Africa, “recast[ing] traditional U.S. policy priorities—democracy and governance, peace and security, trade and investment, and development—as pathways to bolster the region’s ability to solve global problems alongside the United States,” it does not contain strong enough guarantees that the U.S. will not remain partners with malign actors who also promise to adhere to U.S. counterterrorism objectives.

The essential issue remains that—absent a fundamental recalibration of U.S. foreign policy on the continent and a commitment to really focus on the welfare of ordinary Africans—the United States faces an underlying credibility issue in Africa that can and will poison any attempt to achieve the goals of fostering open societies, delivering democratic dividends, advancing economic opportunity, and supporting a just energy transition. What the United States needs is not a new quadrennial approach to the continent, but rather a fundamental reimagining of how the U.S. pursues its interests abroad, especially in Africa.

A More Human-focused U.S. Foreign Policy

Back in early 2020, before the Biden administration took office, U.S. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan, Director of Policy Planning at the State Department Salman Ahmed, and a number of other authors participated in the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace’s Task Force on U.S. Foreign Policy for the Middle Class, which resulted in one of the most ambitious and wide-ranging foreign policy documents authored in recent years, “Making U.S. Foreign Policy Work Better for the Middle Class.”

The final report advocated integrating U.S. foreign policy into a national policy agenda, aimed at enhancing economic prospects for the U.S. middle class through a number of efforts—from tackling the inequitable distribution of benefits of globalization’s continued spread to breaking down traditional silos between domestic and foreign policy in order to create better trade agreements—as, “a strong and prosperous middle class bolsters economic mobility, and strengthens social cohesion,” while also providing, “a ready and healthy workforce to power the national economy and [fund] a large tax base to pay for national security and social insurance programs.”

However, while the report’s general premise has generally remained emphasized, even in the Biden administration’s October 2022 National Security Strategy, U.S. support of Ukraine has led to a situation where, “American citizens are feeling the punishing effects of global economic sanctions against Russia,” as in the months leading up to and following the Russian invasion, “prices for fuel, food, rent, and other good surged due to pandemic labor shortages and supply-chain bottlenecks.”

Therefore, while it is too early to render a final verdict on the relative success or failure of the Carnegie Endowment Task Forces’ foreign policy for the middle class, as we approach a year of war in Ukraine, it is perhaps time to ask whether there is a better way to achieve a transformed U.S. foreign policy that benefits not only the U.S. middle class but also our African partners’, while simultaneously reducing accusations of hypocrisy and double-standards that continue to plague U.S. efforts abroad.

As such, it is time for a new foreign policy where U.S. activities better align with its rhetoric, so that statement’s like President Biden’s February 2021 exhortation to State Department personnel that, “we must start with diplomacy rooted in America’s most cherished democratic values: defending freedom, championing opportunity, upholding universal rights, respecting the rule of law, and treating every person with dignity,” do not run afoul of continued U.S. support for strongmen and dictators throughout the continent. A foreign policy that works for the American middle class is excellent; a foreign policy that works for our partners’ middle class as well is better.

The China and Russia Challenge

Shortly after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Western leaders pushed African and Asian leaders at the United Nations to condemn the attack, with a United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) vote that resulted in 143 countries voting in favor, five countries against, and thirty-five abstaining. A later UNGA vote to suspend Russia’s membership in the UN Human Rights Council saw ninety-three countries vote in favor, with twenty-four against, and fifty-eight abstaining countries—the majority of those in Africa, including Ethiopia, Mozambique, and Uganda, amongst others.

All of this comes after a period of time where Chinese firms had become more active in building roads, ports, and rail throughout Africa as part of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative, as, “from 2007 to 2020, Chinese infrastructure financing for sub-Saharan Africa was 2.5 times as big as all other bilateral institutions combined.” Furthermore, perhaps even more important than the breadth of Chinese investment is its speed. As has been argued by former Senegalese President Abdolaye Wade, China moves faster than the West when it comes to such projects, noting that, “a contract that would take five years to discuss, negotiate and sign with the World Bank takes [just] three months when we have dealt with Chinese authorities,” leading to the average BRI infrastructure project taking just 1⁄3 of the time required by similar World Bank or African Development Bank projects.

However, despite China’s increased flexibility, the picture is not entirely rosy when it comes to these Beijing-funded projects. As a May special report in the Economist noted, “China prides itself on a “demand-driven” approach: doing what African leaders want, to hell with technocrats in finance ministries.” Furthermore, a 2018 paper by Ann-Sofie Isaksson and Andreas Kotsadam in the Journal of Public Economics found that, “living within 50 km of sites where Chinese projects are currently being implemented is, indeed, associated with a greater probability of having experienced corruption,” and that the authors, “do not find an equivalent pattern around World Bank project sites.” Fundamentally, as the May Economist special report concludes, while there is little to claims of China being engaged in so-called “debt-trap diplomacy” in Africa, it is more accurate to say that while, “China may not be a duplicitous negotiator…it is ruthlessly self-interested.” It is China’s, “‘muscular’ approach, with strict confidentiality clauses, requirements that China be repaid ahead of others and the use of escrow accounts,” that does indicate that it does not have the good of Africans at the heart of its programming.

In addition to China, there remains a strong Russian presence on the continent as well. As CSIS’s Mvemba Phezo Dizolele noted before the House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, and Global Human Rights & Europe, as well as the Subcommittee on Energy, the Environment and Cyber, African states do not have the same adversarial relationship with Russia that much of the West does, noting that, “for several African countries, these ties with Russia preceded their independences, as the Russians supported them in their liberation struggles against colonial powers.” Furthermore, Dizolele pointed out to the committees that, “even though Russia suffered a major setback after the disintegration of the Soviet Union, it maintained its presence in Africa and kept its vast network of friends across the continent.” Ultimately, Dizolele notes, “to date, the Russian Federation has defense cooperation agreements with twenty-seven countries, including Libya, Sudan, Cameroon, Angola, Tanzania, and Zambia,” which include services ranging from from the exchange of defense and security policy information to military education and even the discussion of the entry of Russian warships into African ports.

More concerningly, Russia has recently sought to bolster those ties to the African continent, with Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov undertaking a four-nation Africa trip in July which included stops in American partners Egypt, Ethiopia, Uganda, and the Republic of the Congo. His trip comes after a 2019 Russia-Africa summit which was attended by Vladimir Putin and forty-three African leaders as well as a 2020 report by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute which named Russia as Africa’s premier source for arms imports. More specifically, Russia has also announced plans to enhance military and technical cooperation with an Ethiopian government that has been accused of war crimes and human rights violations, increased its use of abusive private military contractors throughout the continent—even after failures in countries like Mozambique—and maintains a robust political and military relationship with Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni whose police and security forces have been credibly accused of torture and other abuses.

However, Russia too has been credibly accused of pursuing its own ulterior motives on the continent, with the U.S. Ambassador to the UN Linda Thomas-Greenfield arguing before the Security Council that, “one of the most immediate and growing concerns in Africa is the Kremlin-backed Wagner Group’s strategy of exploiting the natural resources of the Central African Republic, Mali, and Sudan, as well as other countries.”

In the end, what China and Russia offer their African partners is a transactional relationship that does not come with the persistent hectoring about human rights or democratization that typically accompanies a partnership with Western nations. However, while a relationship with Russia or China might be seen as no-string-attached by some African governments, these partnerships are frequently not aimed at the good of the African populace but rather the enrichment of the foreign partner or the benefit of the political careers of embattled African leaders such as Colonel Assimi Goïta in Mali or Faustin Archange Touadéra in the Central African Republic. As the Brookings Institution’s Joseph Siegle wrote back in February of this year, “to assess the future of Russia-Africa relations, therefore, it is necessary to be clear that the ‘partnerships’ that Russia seeks in Africa are not state- but elite-based. By helping these often illegitimate and unpopular leaders to retain power, Russia is cementing Africa’s indebtedness to Moscow.”

Meanwhile, Beijing’s influence is more subtle but no less malign for ordinary Africans, as the country has used its increased commercial ties across Africa as a vector to promote its own authoritarian model of the future internet. Specifically, in Ethiopia, Chinese firms ZTE and Huawei were chosen as the country’s partners for a 4G network rollout, with the same firms also being selected to run a pre-commercial 5G services trial, as well. As international NGO Freedom House argued in their 2022 country report on Freedom on the Net in Ethiopia, “these relationships have led to growing fears that Chinese entities may be assisting the authorities in developing more robust information and communications technology (ICT) censorship and surveillance capacities,” a particular problem given that, “government surveillance of online and mobile phone communications is pervasive in Ethiopia,” and that, “Ethiopia’s telecommunications and surveillance infrastructure has been developed in part through investments from Chinese companies with backing from the Chinese government, creating strong suspicions that the Ethiopian government has implemented highly intrusive surveillance practices modeled on the Chinese system.”

A More African-Focused Foreign Policy

With Russia and China primarily looking out for their own interests in Africa, it creates a space for the United States to step in and take on the role of the foreign partner who not only aims to take care of its own citizens, but looks out for the good of the average African, as well. Such a strategy may be initially more costly, and will run into the headwinds of a disappointingly still pervasive environment of military takeovers on the continent, but will have the benefit of positioning the U.S. as a true partner to sub-Saharan African populations that are expected to double over the next three decades.

Just as with the Carnegie Endowment’s Foreign Policy for the Middle Class, what is needed in a new U.S. foreign policy towards Africa is a rebuilding of trust. However, that trust needs to be built not just with the elite leaders of African nations, but with their people. To that end, there are a number of overarching recommendations that bear highlighting.

First, and most importantly, the U.S. needs to be ready to immediately sever the flow of security assistance when human rights or democratic values are being trampled upon by African partners’ leadership. Too often, U.S. involvement in countries such as Ethiopia, Mozambique, or Uganda is simply viewed through the lens of whatever the security crisis of the moment is and not as part of a long-term relationship between the United States and the people of that country.

For instance, when it comes to Uganda, despite a 2022 Human Rights Watch report that documented, “years of enforced disappearances, arbitrary arrests and detention, torture, rape, extortion, and forced labor by Ugandan security forces,” and the country’s top 30 ranking as one of the world’s countries most at risk for the onset of mass killings, the country is still a major recipient of U.S. foreign aid, totaling some $8.1 billion in the period between 2001 and 2019, as well as the lion’s share of $2 billion in train and support assistance for participation in the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM)—a country where the U.S. still maintains a strong interest in fighting al-Qaeda, but that it also wishes to keep at an arms distance due to its own poor experiences there in the 1990s. While back in 2014, the U.S. did cut aid flows to Uganda and canceled a regional military exercise in response to a Ugandan law imposing harsh penalties on homosexuality, that military aid was eventually resumed despite the Museveni government’s attempts to resurrect the anti-gay laws and even extend them so as to be able to impose the death penalty on homosexuals in the country.

Similarly, in Mozambique—where U.S. special forces troops last year began training Mozambican forces to fight Al-Sunna wa Jama’a (ASWJ) in Cabo Delgado—U.S. aid is still provided despite the fact that, as former U.S. ambassador to Mozambique Dennis Jett wrote in Foreign Policy in March 2020, “Mozambique has become a borderline failed state, its democracy a sham, and its energy riches won’t guarantee that its security or governance will improve in the future.” Moreover, the United States continues to support its partners in Maputo despite eight major civil society observer groups noting that the country’s October 2019 elections, “were not free, fair and transparent and the results are not credible,” citing “irregularities” in the counting of votes, the lack of an “audit trail” registration, and ballot-box stuffing among other forms of Frelimo vote inflation.

Disappointingly, while the U.S. does have some interest in degrading ASWJ’s ability to operate, it hard to currently imagine a continued American interest in Mozambique’s ills if it were not for the $30 billion investment that American multinational ExxonMobil has in Mozambican liquified natural gas, or possibly American partner France’s TotalEnergies’ $20 billion worth of natural gas projects in the country.

Second, the United States must construct its future relationships not only with African elites in politics and business in mind, but with ordinary Africans who often do not receive the benefits of their governments international collaborations with Russia or China. As was noted in a May special report for The Economist, not only do Africans find it difficult to reach senior levels in the Chinese firms that have poured into the continent in recent years, but, “in Congo and elsewhere Chinese miners have fostered poor labour practices,” and, “in Nigeria Chinese cartels in ceramic and wigs have locked out local competitors.” Furthermore, “environmental degradation is common,” the report notes. Despite this, as another contemporaneous Economist report notes, the U.S. overall response has been underwhelming, as the Biden administration’s Build Back Better World—an attempt at a “values-driven, high-standard, and transparent infrastructure partnership led by major democracies to help narrow the $40+ trillion infrastructure need in the developing world”—has major flaws, as “B3W is little more than a new label for inter-agency co-operation in Washington.”

Third, the United States will need to take more steps to own its responsibilities on the continent, including when it comes to its common but differentiated responsibility for the enormous impact that global warming has had and will continue to have on the African continent. Mercifully, this seems to be a point that the Biden administration has at least acknowledged, with the U.S. recently dropping its long-held objections to providing compensation for the costs of the destruction brought on by climate change. By doing so, the U.S. can not only deliver tangible progress towards global emissions reductions, but address the fact that nearly half of the continent’s population lack adequate access to electricity.

However, more needs to be done to recognize the disproportionate impact that decades of American emissions have had on a sub-Saharan Africa that presently emits just 0.55% of the global total. Moreover, as Jack A. Goldstone has written for the Wilson Center, “even on an income-adjusted basis, African countries are low CO2 producers,” with U.S. CO2 output 160 times that of Ethiopia and twenty-three times higher than the more urbanized Nigeria.

Recognizing this disproportionate impact last year, China had announced a halt on building new coal-fired power plants overseas—a move welcomed by African environmentalists and others—and has proposed, “to establish a China-Africa partnership of strategic cooperation,” in the fight against climate change, including in the area of green development. In light of that, the United States will need to step up its efforts to boost Africa’s supply of sustainable energy, whether through efforts such as the joint U.S. and EU cooperation promoting projects such as the African Continental Power System Masterplan or USAID’s Power Africa program.

Fourth, and largely related to the first point, the United States needs to be less concerned with fighting the Global War on Terror in Africa and more concerned with the underlying drivers behind these actors. As Jihad Mashamoun recently wrote in a piece for the Middle East Institute, a country such as Sudan—which is geostrategically important to U.S. interest in both Africa and the Middle East—has leaders in Lt.-Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and his deputy Lt.-Gen. Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (also known as “Hemedti”), which, “are banking [on their geostrategic importance] as they seek to press the Biden administration to focus its Sudan policy on stability, rather than supporting calls for democracy.”

As Mashamoun points out, “both Burhan and Hemedti have worked to encourage the U.S. to continue its counter-terrorism cooperation with Sudan,” with the, “aim…to convince the U.S. to drop its support for popular calls for democracy and accept their autocratic military rule.” Mashamoun further notes that the Bush and Obama administration’s focus on stability and counter-terrorism was a result of the demands of the war on terror, which saw the Bashir regime offer to share intelligence on Islamist groups in the country as part of a hoped-for normalization of relations.

While normalization was, in the past, impeded by Bashir’s involvement in the Darfur conflict and genocide, the Obama administration still ultimately decided to ease sanctions on its way out of the door in order to reward the Bashir regime for its counter-terrorism commitments. Further endeavoring to make the U.S.-Sudan relationship more transactional, the Trump administration removed Sudan from the state sponsors of terrorism list in exchange for Khartoum agreeing to join the Abraham Accords. In addition, the deal was also contingent on Sudan finally paying $335 million in restitution for victims of the 1998 bombings at US embassies in Tanzania and Kenya, as well as the 2000 attack on the USS Cole and the murder of a USAID employee in the Sudanese capital.

While the Biden administration has subsequently suspended Abraham Accords-related assistance to Sudan due to the coup d’état that dissolved the military-civilian Sovereign Council that was to guide the country on its path towards democracy, the administration has reiterated its commitment to advancing the Abraham Accords, stating that, “they are a positive development that have had clear benefits for Israel and the region,” making it likely that full democratization will not be one of the requirements for Sudan to resume receiving Abraham Accords funding.

Reckoning With the Link Between the U.S.’ Self-Conception and African Perceptions of American Aid

One of the fundamental problems with American foreign policy towards Africa since the end of the second World War and especially since the end of the Cold War is that the United States’ unquestioned global primacy frequently resulted in a clash between American rhetoric about being the shining city on a hill—helping to usher the rest of the world’s population to their free, prosperous, and democratized future—and actual American foreign policy, which, instead of supporting the rights and freedoms of Africans, has often aided the very men who have sought to oppress their own fellow citizens.

As Tobias Hagmann and Filip Reyntjens write in their excellently edited book, Aid and Authoritarianism in Africa, not only has, “the relationship between foreign aid and autocratic rule in sub-Saharan Africa has a long-standing historical precedent,” but, “in the past decade, important donors have gradually traded their earlier commitment to political reform in Africa for the achievement of increasingly technocratic development successes such as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and, more recently, the ‘development effectiveness paradigm’ with its focus on growth and productivity.” As a result, the authors point out, “while bilateral and multilateral donors constantly claim to be promoting democracy, good governance and human rights in Africa, many are effectively complicit in fostering development without democracy.”

More specifically, as Rita Abrahamsen notes in her chapter of Aid and Authoritarianism, towards the end of the Cold War, the U.S.—and others in the West—immediately began to see democracy rise, “from obscurity to become the panacea for Africa’s development ills,” as the World Bank’s 1989 report, “Sub-Saharan Africa: From Crisis to Sustainable Growth” put forth the argument that, “a ‘crisis of governance’ underlies the ‘litany of Africa’s development problems,’” with the overall message of the report being that, “liberal democracy was not only a human right, but also conducive to and necessary for economic growth.” As such, “in February 1990, the United States announced that foreign assistance would be used to promote democracy and would favour countries pursuing ‘the interlinked and mutually reinforcing goals of political liberalization and market-oriented economic reforms.”

Despite this professed belief in the power of liberal democracy to transform socio-economic life in Africa, however, Abrahamsen argues, “the pursuit of simultaneous economic and political reform presented newly elected governments in the 1990s with complex and intractable dilemmas, where economic and political logic often appeared contradictory and conflicting: on the one hand, the demand for further economic adjustment by donors and creditors, and, on the other, domestic expectations of social improvements in the wake of democracy; on one side, instructions to privatize state-owned enterprises and, on the other, hopes for gainful employment,” leaving African governments torn between the demands of external donors to liberalize their markets and the desires of their own domestic constituencies for more public goods.

Abrahamsen further argues that, as a result, “the first casualty of this dilemma was the democratic process itself, as governments reverted to the tried and tested methods of the authoritarian past in order to contain civil disorder and silence critics,” which was a process seen in Zambia in the early 1990s, where, faced with IMF and World Bank demands to cut spending on public services and pursue greater trade liberalization, the economy shrank dramatically and, “the government of President Chiluba reacted by closing down democratic space, harassing the opposition, and rigging elections.”

Abrahamsen also notes that often while, “between elections, significant breaches of democratic practice will lead to the suspension of assistance,” or assistance being withheld in the lead-up to elections in protest against undemocratic practices, “almost without fail, however, foreign aid is reinstated in an almost ritual performance.” She notes how ,”Uganda, for example, has periodically encountered the wrath of donors in response to its authoritarian practices and persecution of the opposition, but aid has inevitably been restored to a country that has become a ‘donor darling’ due to its economic liberalization, its successful HIV/AIDS campaign and more recently its support for counterterrorism,” despite the fact that, “Uganda is a de facto one-party system, which according to the Afrobarometer’s surveys has one of the continent’s biggest gaps between citizens’ demand for democracy and its perceived supply.”

Correspondingly, “reviews of Africa’s democratic experiences thus often conclude that Africans are disappointed with democracy’s ability to reduce poverty, inequality, and suffering,” and, “as Peter Lewis observes, ‘growth has not been accompanied by rising incomes or popular welfare’, giving rise to the paradox of ‘growth without prosperity.’” Resultantly, “to date, there are few signs that the spectacular double-digit growth experienced by many countries since the mid-2000s has significantly improved…socioeconomic conditions, and recent surveys conducted by the Afrobarometer,” show that, “53 per cent of respondents rated the state of their national economy as ‘fairly bad’ or ‘very bad’, and 48 per cent described their personal living conditions as ‘fairly bad’ or ‘very bad’.” Ultimately, Abrahamsen concludes, “the effects of simultaneous economic and political liberalization can be seen as paradoxical; they contribute both to the maintenance of (an imperfect) democracy and the persistence of social and political unrest, which in turn pose a continual threat to the survival of pluralism.”

Abrahamsen also points out that further complicating the U.S.-Africa development relationship is the fact that, “one of the characteristics of contemporary development assistance is an unashamed acknowledgement that it must serve the national security interest of donors,” with the assumption that development and security goals can be pursued in a simultaneous and mutually reinforcing manner. In essence, Abrahamsen argues, U.S. development discourse, “has coalesced around the three ‘Ds’ of development, diplomacy and defence,” where, “the three ‘Ds’ are considered mutually reinforcing tools of foreign policy that are in turn integrated into an overall security strategy.” Moreover, Abrahamsen points out that for Western governments, “the three ‘Ds’ of development, diplomacy and defence come together in a concern for the national security of donors, and there is little doubt that security today figures more prominently on the development agenda than at any other time since the end of the Cold War,” such that, “this discourse constructs the development needs of the poor as coterminous with the security priorities of donors, and there is little or no room for conceiving of conflict or contradictions between them.”

At the end of the day, the issue is more about what happens when the priorities of donors and recipients are out of alignment, such as with the United States’ Trans-Saharan Counter-Terrorism Partnership, whose five objectives contain three which refer to security and two others that refer to, “promoting democratic governance,” and “discrediting terrorist ideology.” Abrahamsen notes that, “the inherent danger in this order of priorities is that foreign assistance ends up being driven by donors’ security interests rather than the development needs of recipient countries,” such that, “in Uganda, President Museveni has…successfully played the ‘war on terror’ to his advantage, bargaining strategic support for increased assistance and political negotiating space,” while, “progress on democracy has stalled…with human rights organizations frequently expressing concerns about freedom of expression, persecution of civil society, and harassment of the opposition.” Furthermore, Abrahamsen submits, elsewhere, “in North Africa, Algeria has become pivotal in the fight against violent extremism in the Sahel, and has benefitted from considerable foreign assistance despite its poor record on democracy and human rights.”

As Abrahamsen admits, “there is nothing inherently undemocratic about training and funding police and militaries.” However, “the substantial allocation of resources and development assistance to security efforts raises numerous questions and challenges,” and that, “given the frequency of military coups and the tendency of African militaries and police to be focused on regime security rather than citizen security, strengthening a state’s security apparatus is potentially hazardous both for the survival of democracy and the protection of human rights,” especially as, “Ethiopia has suppressed opposition parties and journalists by branding them ‘terrorists,’” and Uganda’s, “Museveni has linked the Lord’s Resistance Army to the war on terror and al-Qaeda in order to attract foreign assistance.”

The result, Abrahamsen points out, is that, “the current discourse on development, security and stability constitutes a resource that African leaders can employ to their own advantage, frequently enhancing their own security apparatus while weakening the opposition and civil society critics.”

In general, this is something that African publics’ are well aware of. Furthermore, Africans can easily see through veiled U.S. attempts to play geopolitics with African aid. As Chris Ogunmodede, associate editor at World Politics Review recently said of U.S. Secretary of State Blinken’s trip to Africa in August, “If it’s about competing with China (and Russia) in those terms, it’s going to fail. It’s not about what Africans want. It’s all about what Washington wants. That’s not a partnership.”

Evaluating the U.S. Position in Africa Vis-à-vis Russia and China

Another fundamental challenge that the United States must face as it attempts to reassess its engagement with African countries is that it no longer is the globe’s unquestioned economic leader. As the Brookings Institution’s Africa Growth Initiative wrote in January’s, “Foresight Africa: Top Priorities for the Continent in 2022,” in the last two decades, China has gone from being the top trading partner for just two African countries to being the top trading partner of 29 African countries, “including the continent’s three largest economies—Nigeria, South Africa, and Egypt.” Furthermore, Brookings notes, by 2020, the U.S. was no longer the top trading partner for any African country, especially as, over the period between 2006-2016, “trade between the United States and sub-Saharan African countries…stagnated or declined,” as, “exports from sub-Saharan Africa to the U.S. fell by 66 percent…while imports grew by only 7 percent, even as overall imports rose by 56 percent.”

Furthermore, despite what continues to be an epic blunder in Ukraine which has dealt a massive blow to Russian military prestige and economic power, it is likely that the country will still remain a major remain a player in, “the global South, where Russia enjoys greater influence and is able to contest,” narratives of its decline. However, while, “Russia is not investing significantly in conventional statecraft in Africa— e.g., economic investment, trade, and security assistance,” the country has relied on, “ a series of asymmetric (and often extralegal) measures for influence—mercenaries, arms-for-resource deals, opaque contracts, election interference, and disinformation,” which tend to focus, “on propping up an embattled incumbent or close ally: Khalifa Haftar in Libya, Faustin Archange Touadéra in the Central African Republic (CAR), and coup leaders Colonel Assimi Goïta in Mali and Lieutenant General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan in Sudan, among others.”

Therefore, while a good first step for engagement with African countries will be to reinvigorate the flagging trade between the U.S. and Africa, as has been argued earlier this year by the CNA Corporation’s Alexander Casendino, a more vital reengagement must be with democracy, human rights, and governance (DRG) programming, an area where just 4% of U.S. security assistance funds in Africa went in 2019.

To achieve this focus on democracy, human rights, and governance, the U.S. will need to show greater resolve towards threats offered by African leaders who resist such efforts. Particularly, as David M. Anderson and Jonathan Fisher write in their chapter of Aid and Authoritarianism on with regard to authoritarianism and the securitization of development in Uganda over the past three plus decades. There, the U.S. will need to stand ready to call the bluff of leaders such as Uganda’s Yoweri Museveni who, in 2012, threatened to pull out of the African Union Mission in Somalia due to the U.S. potentially supporting a UN report which claimed that Rwanda and Uganda continued to support M23 rebels committing war crimes in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. As Anderson and Fisher point out, “US and UK officials were largely convinced that Uganda’s 2012 threat…was a bluff, but were nonetheless unprepared to ‘call’ the Ugandan leader on this particularly disingenuous piece of diplomacy.”

When a partner is engaging in such egregious behavior and the U.S. does nothing to alter the relationship, it sends a powerful signal to not just that partner but the United States other existing—and potential future—partners that the U.S. is open to trading its principles for stronger security cooperation.

In the final analysis, one of the strongest negotiating tactics a larger, more economically powerful country such as the United States has is the ability to determine when and where it is willing to walk away from the table because the other side is demonstrating its unwillingness to budge on an issue of fundamental importance—such as democracy, human rights, and governance issues should be for the U.S. Indeed, the U.S. must first demonstrate a commitment to walk away from relationships with leaders that have taken an authoritarian turn if it wants to reassert its proper role as the dominant player in the bilateral relationship. By permitting poorly-performing partners to not only continue to trample on their citizens rights, but to threaten to jettison the American partnership when the U.S. criticizes their behavior—such as Uganda’s Museveni did in 2014 when, in response to Western donors’ condemnation of his signing of the country’s anti-homosexuality law, he declared that, “I want to work with Russia because they don’t mix up their politics with other country’s politics,”—it deals a massive blow to U.S. rhetorical proclamations about its support for democratic values and human rights.

At the end of the day, Washington must understand that while it is true that Russia and China have made tremendous inroads into Africa in the past two decades, the answer to combatting their rising influence is not to abandon the Western promotion of democracy and human rights but to instead re-center that pursuit in all of its engagements on the continent. While the U.S. does have a number of legitimate security interests throughout the continent, none of them can be addressed by propping up the leaders who end up being one of the primary underlying drivers behind the continent’s unrest themselves.

Drifting Partners in Mali and Chad

For instance, if Uganda’s Museveni wants to continue his drift towards Moscow, then the U.S. should stand ready to halt all security cooperation with the country, cutting off transfers such as the $270 million in military assistance that the regime received during the Obama administration’s time in office. While such an aid cutoff should not necessarily affect the provision of development or humanitarian aid, in the event of such continued recalcitrance and poor behavior from the Ugandan leader, the U.S. must also stand ready to re-evaluate how such aid flows are being used by the regime and punish malfeasance, especially if a leader like Museveni continues to flout U.S. norms regarding human rights in his country.

As Chairman of the U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations Robert Menendez said back in April, “despite [their] troubling track record, Uganda remains one of the top recipients of U.S. foreign aid and security assistance,” and that, “while the U.S. has issued statements and expressions of concern after human rights violations come to light, such statements are insufficient. Personal targeted sanctions would have greater impact.”

Moreover, elsewhere, in the Sahel, the U.S. should be ready to change tactics in its decade-long adventure battling jihadist insurgencies in countries such as Mali, Chad, and Burkina Faso, where years of poor governance has been compounded by a recent spate of military takeovers that have only increased regional instability. While the U.S. should certainly not consider abandoning its humanitarian role in these countries, it must seriously consider cutting off all security-related assistance in order to clearly send the message that American leadership will not tolerate coups and that civilian democratic governance is the sine qua non of the bilateral relationship. For far too long, the United States has simply limped along with these partners while their leaders have slow-walked efforts towards democracy.

Mali, for instance, provides a credible case study not only in how the failures in democratization and reform have led to the state the country is in today, but that the continued support of outside donors allowed Malian leadership to continue with the fiction that it was making progress. This idea is demonstrated by Leonardo A.Villalón, whose article, “The Political Roots of Fragility in the G5 Sahel Countries: State Institutions and the Varied Effects of the Politics of Democratisation,” appears in the Institute for International Political Studies’ book, Sahel: 10 Years of Instability: Local Regional and International Dynamics, edited by Giovanno Carbone and Camillo Casola. In the article, Villalón notes how, with the exception of 1992, Mali has never had “robust and widely-accepted elections”, and that President Amadou Toumani Touré’s reign from 2002-2012 served to further erode existing democratic institutions. As a result, “the Malian democratic state was a hollow shell which existed largely to broad international applause, what has been evocatively labeled a ‘Potemkin state’,” where, “the institutions of Malian democracy and the elite that populated them had little popular legitimacy, and this despite the fact that they were much praised by the international community.”

Despite these failures, the U.S. has continued its relationship Mali in recent years, providing nearly $79 million in U.S. foreign development assistance in 2020, with only 1% reserved for democracy, rights and governance and just 5% for peace and security programming that is not direct aid to the security services, as has been noted by the United States Institute of Peace’s (USIP) Ena Dion and Emily Cole. Furthermore, this does not even take into account the portion of the $346 million in aid the U.S. provided as part of its funding towards the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali’s (MINUSMA) budget. As Kristen A. Harkness wrote back in May in a piece for the Modern War Institute at West Point, “the United States, in other words, is predominantly building up the military capabilities of authoritarian governments in sub-Saharan Africa.

Elsewhere, one might also consider the case of Chad, where a Transitional Military Council has taken over after the death of Idriss Déby in April 2021. Despite the military takeover, the U.S. has continued to provide the country with funding through the Trans-Sahara Counterterrorism Partnership and the G5 Sahel Joint Force, including nearly $2 million for International Military Education and Training (IMET) and conventional weapons security. Furthermore, Chad’s Idriss Déby had continued to receive American support despite a system of violent repression that was created to keep him in power. Now, even today, the U.S. seems prepared to continue such support in order to keep counter-terrorism operations such as the G5 Sahel Joint Force or MINUSMA operational. Meanwhile, citizens in Burkina Faso, Chad, and Mali’s neighbors simply hope that the coups and unrest do not come for them anytime soon.

This situation is completely untenable, and U.S. actions in the region continue to be supremely counterproductive. As USIP’s Sandrine Nama and Joseph Sany wrote back in October:

U.S. and international policymakers need to recognize the Sahel as a core of one of the world’s biggest security crises — a contiguous swath of countries destabilized not by some inexplicable predilection to violence but by a visible root cause: toxic governance. Generations of corrupt, authoritarian rule by elites rather than laws has prevented or undermined democracies, investments and the fulfillment of basic human needs. These failures of governance have bred violent extremism, communal conflicts and military coups or attempts in varied mixes among a half-dozen Sahel states — a zone of 138 million people that is nine times bigger and more than triple the population of either Afghanistan or Iraq.

Prior responses by the U.S, France, and the UN have been largely counterterrorism-focused, which has not only failed to reduce the violence, but has actually exacerbated it. While it has become cliché to point to the old twelve-step saying that insanity is doing the same thing over and over again, and expecting a different result, it is, however, more than apt when it comes to American and overall Western actions in the Sahel. Ever since the 9/11 attacks, the U.S. has seemingly viewed the continent solely through the lens of combatting “terrorism”, and has, as a result, ended up in a proverbial game of whack-a-mole against individual terrorist groups rather than confronting the real problems that lie beneath these insurgencies.

A New Way Forward

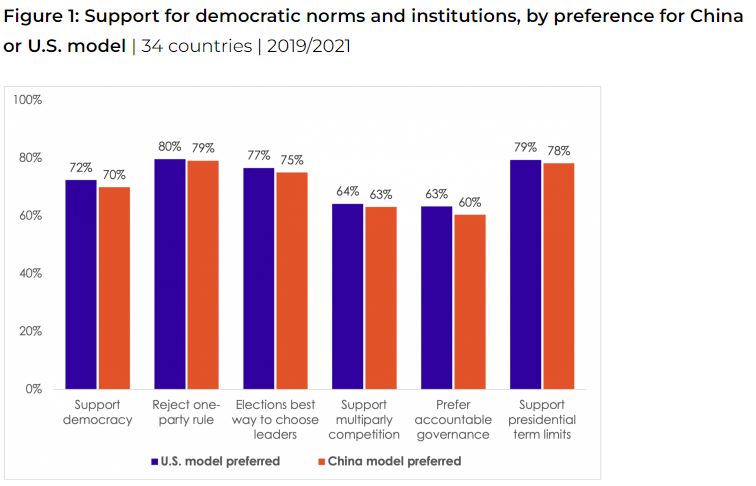

While there is little doubt that both Russia and China will continue to seek out relationships with African countries—especially ones experiencing a democracy deficit such as in Mali or Burkina Faso—both of those great powers are faced with the fact that one in three Afrobarometer respondents in 2021 listed the U.S. as their favored development model, with just 22% preferring China, and Russia not a major consideration. Furthermore, last year’s Afrobarometer report also finds that, “Africans who prefer Chinas as a development model…[are] about as likely as those who favor the U.S. model to express support for democracy, elections, multiparty competition, and accountable government, and as likely to reject authoritarian alternatives such as a one-party state or military rule.” While Africans tend to reject strict conditionality being attached to development funds, it does not mean that they wish the U.S. to continue to support leaders who oppress them.

That being said, the United States is never going to see real change from partners in Africa, or anywhere else in the world for that matter, if it does not begin to be ready to make some tough decisions in the coming years. However, the early results are not particularly heartening. For instance, in July, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for African Affairs of United States Chidi Blyden testified before the Senate Foreign Relations committee that, “as the Transitional Military Council works towards a return to democratically elected and civilian-led government, [the United States] remain[s] committed to supporting the Chadian people,” and that, “the United States has the potential to provide meaningful security cooperation to train Chad’s military and civilian services, especially given its role as a troop contributor in UN and regional peace operations.” More disappointingly, Blyden’s analysis of the Sahelian context not only bought the Transitional Military Council’s line that it is indeed working towards a return to civilian-led government—and not figuring out a way to indefinitely extend its own rule—but it seemingly ignored the terrible legacy left by former Idriss Déby and his grip on power through military means.

In sum, it does not matter how strong a counter-terror partner countries like Chad, Mali, Burkina Faso, Mozambique, Ethiopia, or Uganda are if their leadership continues to oppress large segments of their populations in order to maintain power or control. As the 2015 United Nations Plan of Action on Preventing Violent Extremism acknowledges, “Nothing can justify violent extremism, but we must also acknowledge that it does not arise in a vacuum. Narratives of grievance, actual or perceived injustice, promised empowerment and sweeping change become attractive where human rights are being violated, good governance is being ignored, and aspirations are being crushed.” Furthermore, as Marc Sommers recently wrote for Just Security, “violent extremist groups infiltrate African nations where predatory governments alienate youth, exclude vulnerable groups, and rule with violent impunity. The intruders easily exploit massive fault lines in state-citizen relations…and that is where the international response to violent extremism in Africa must focus.”

While the Biden administration’s U.S. Strategy Towards Sub-Saharan Africa deserves some plaudits for acknowledging the fact that, “there are strong linkages between poor and exclusionary governance, high levels of corruption, human rights abuses, including sexual and gender-based violence, and insecurity, which are often exploited by terrorist groups and malign foreign actors,” the document provides little tangible guidance on how exactly the Departments of State or Defense will go about putting governance goals above counterterrorism commitments.

In the end, what the United States needs to do is to be ready to stand up to African strongman leaders who are unwilling to relinquish their militarized grips over their populations. Should those leaders fail to do so, the United States needs to be ready to completely walk away from any kind of security relationship with those countries, even if it means permitting China and Russia to step in to temporarily fill in the gap. In the long-term, what the United States should instead do is continue to provide lifesaving humanitarian assistance as well as to work to reconfigure the U.S. visa system to make it less hostile to Africans who wish to come to the country to take advantage of our world-class higher education system. Longer-term, in countries where military-focused leaders deny their citizens the right to determine their own futures through the ballot box, the United States should stand ready to cut off all military-related aid—including for counter-terrorism purposes—as, even if those countries achieve some small tactical victories due to American assistance, they are simply creating the underlying conditions for future insurgencies and unrest.

While such a strategy would undoubtedly cause some short-term pain—possibly even severe—ripping the band-aid off of the situation will, in the long run, do much more to achieve the goals of not only American policymakers but of ordinary Africans as well. Furthermore, with continued population growth that will make Africa home to just shy of 25% of the global population by 2050, the problems facing the continent’s democratically-challenged countries will only get worse as climate change—and its resultant displacement of people—trigger even greater unrest and discontent with the often miserable status quo. Going forward, the United States either has the choice to try and ameliorate this situation, or to double-down, making it worse, while attempting to keep “Africa’s problems” contained in Africa.

Continuing to pursue the same kind of helter-skelter counterterrorism strategy is not only counterproductive, it evinces a troubling dearth of creative thinking in the American foreign policy establishment. While the past few decades has seen the U.S. military become the only branch of the government that receives enough funding to be even partially as competent as it needs to be to properly accomplish its objectives, it has left decision makers with the idea that only securitized responses can offer meaningful change.

While the U.S. should certainly not be dictating to Africans the solutions to their problems, in countries that have experienced military takeovers in recent years, the U.S. should at least work to encourage national dialogues to aid in the return towards democracy. In the event that junta leaders are unwilling to go along with these processes, then the U.S. should be willing to walk away from everything in the relationship that does not directly support the lives and livelihoods of the civilian populace.

As Dennis Jett wrote back in 2020 in the pages of Foreign Policy about Mozambique, “the donor community ignores corruption and continues to offer humanitarian and development aid that is little more than a Band-Aid. Treating the basic cause of the country’s ills—bad governance—rather than the symptoms of the problem seems beyond the attention span of the rich countries at variance with their commercial interests.”

The U.S. has proceeded down this path for far too long, at an enormous cost to the U.S. taxpayer, and an even higher cost for the lives of ordinary Africans. As Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs of the United States Molly Phee said at an event back in March, “the United States believes strongly that African voices matter.”

However, according to the 2021 Afrobarometer, Africans have resoundingly rejected military rule, one-party rule, and one-person rule, and just 32% think that their governments are doing fairly or very well when it comes to countering corruption, down from 36% ten years ago. Therefore, when dealing with African countries, the United States should take its own advice and truly listen to the voices of the millions of Africans who reject militarized regimes and begin to use the tremendous leverage brought by American foreign aid to convince African strongmen leaders that U.S. security assistance and their rule by force are mutually exclusive.

The Global War on Drugs’ Impact on Africa

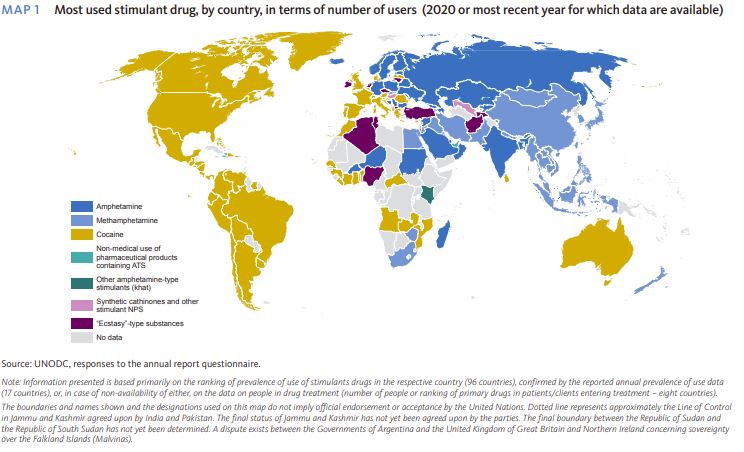

None of this even touches on the more tangential steps that the United States could take to help reduce the disproportionate impact that problems like narcotrafficking have on Africa. For instance, in Mozambique, the insurgency is strengthened through its involvement in the illegal drug trade, which is ultimately fueled by European and U.S. demand for the products. Furthermore, as was pointed out by the UN Office on Drugs and Crime’s (UN ODC) 2022 World Drug Report, transit of cocaine—the most used stimulant drug in terms of number of users in all of the Western hemisphere as well as much of Western Europe—through West Africa has resurfaced in recent years, with seizures in Mali and Niger confirming the trafficking of large volumes of cocaine via the Sahel. What’s more, while the total tonnage of drugs that are trans-shipped through Africa is low when compared to what emerges out of South America, the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) is careful to point out that the total amount of cocaine seized in West Africa in 2019 was larger than reported to the UN ODC. Finally, the EMCDDA writes that an increased number of seizures in the past few years indicates a reversal of a trend from before 2013—with, for example, Mozambique becoming a major cocaine transit hub in recent years—demonstrating that as instability has increased on the continent, the space for narcotrafficking has concomitantly increased.

Human history and practical experience has demonstrated that, as long as drugs exist, there are going to be individuals that wish to consume them. Five decades of a U.S. and European war on drugs has failed to deliver any meaningful progress towards eliminating illegal drugs, and, as the Global Commission on Drug Policy’s 2021 report, “Time to End Prohibition” argues, “over 50 years of prohibition and enormous efforts to eradicate drug production, use and trafficking have not only failed utterly, they have created major security problems and fed violence in urban areas.” Until the United States seriously embraces decriminalization of narcotics, policymakers will have to deal with the fact that America’s war on drugs continues to exist on a global battlefield and that the U.S. is losing, decisively.

As H.L. Mencken wrote nearly a century ago about a different kind of failed war on vice, “Prohibition has not only failed in its promises but actually created additional serious and disturbing social problems throughout society. There is not less drunkenness in the Republic but more. There is not less crime, but more. … The cost of government is not smaller, but vastly greater. Respect for law has not increased, but diminished.” Similarly, until the U.S. grapples with the fact that addiction is a mental health issue and not a criminal justice issue, it is not just ordinary Americans who will get caught up in the destructive wake of the failed war on drugs, but Africans who experience widespread violence at the hands of insurgent groups which are partly sustained by drug trafficking.

Build Back Better for Africans

To further reorient U.S.-African relations, U.S. development assistance in Africa must re-focus on delivering better outcomes for ordinary Africans. While programs such as Prosper Africa and Power Africa have their merits, the Prosper Africa Act has languished in Congress, clouding the future of the nearly $10 billion pipeline for trade and investment. However, as the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace’s Zainab Usman wrote earlier this summer, the draft bill still requires some work if it is to both reach a wide audience of African countries as well as deliver tangible benefits to Africans.

For instance, Usman argues that the legislation, as currently constructed, lacks the focus on specific industries that would make best use of, “the U.S. private sector’s comparative advantage in spaces like pharmaceuticals, digital technologies and higher education.” Furthermore, he correctly argues that Congress should consider different ways of engaging African partners in shaping the legislation, letting policymakers, businesses and civil society both in Africa and the U.S.-based diaspora ensures that the legislation speaks to the real interests of Africans.

Similarly, another U.S. effort that has not achieved its desired results over the past twenty years is the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), which—as was pointed out by the Council on Foreign Relations’ Claire Klobucista back in March of this year—experts have largely judged to be a failure due to its inability to aid many African partner countries in diversifying their economies and increasing their competitiveness in the global market. Moreover, as CSIS’ Laird Treiber wrote back in 2021, “AGOA does not cover many of the sectors with the greatest potential, including the growing trade in financial, digital, travel, and business services,” and that Congress has indicated that it will not re-extend the program in 2025 due to leading sponsors of the legislation arguing that African economies had matured since the program’s creation. This, as Treiber notes, would be a disaster, as letting AGOA expire without a renewal or engaging with sub-Saharan countries on bilateral free trade agreements, “would provide no transition for those companies and countries that have made use of [AGOA], particularly as African countries look to recover from the first continent-wide recession in 25 years.” As such, while the U.S. may want to keep the door open for more bilateral free trade agreements with African partners—especially if they include strong chapters on anti-corruption and the environment—policymakers must also consider extending certain AGOA provisions that affect sectors such as textiles, which had seen soaring trade volumes under the deal.

In a similar vein, the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Catherine Nzuki and Mvemba Phezo Dizolele argue, the creation of the United States Development Finance Corporation has largely been a disappointment in Africa, with a timid investment strategy that has struggled to increase U.S. impact on African markets. As Charles Kenny and Ian Mitchell wrote for the Center for Global Development back in 2020, the Development Finance Corporation could, “provide a lot more financing at rates above their own cost of borrowing to support both the private and public sectors in developing countries.” This could be especially beneficial for U.S. consumers, as Africa is not only home to thirty percent of the world’s strategic minerals, it is poised to be the world’s next growth market.

Steps from the Biden administration, such as removing Ethiopia, Guinea, and Mali from AGOA due to human rights abuses and military coups send an excellent example to other partners whose militaries are considering an attempted takeover, and actions such as this should be considered the gold standard, with provisions to suspend participation included in any future bilateral trade agreement. However, other steps should be considered, such as trade agreements between the U.S. and Africa’s regional economic communities (REC), as not only does the vast majority of intra-African trade takes place within these RECs, but, “importantly, a trade agreement with the [East African Community] would be largely aligned with the spirit of the [African Continental Free Trade Area], whose operationalization is predicated on increased intra-REC trade across the continent,” and, “it would provide a roadmap for engaging other RECs like the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the Southern African Development Community (SADC), the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), and the Arab Maghreb Union (AMU),” as has been argued by the Center for Global Development’s Mike Brodo and Ken Opalo.

Conclusion

Fundamentally, U.S. policy towards Africa will struggle to achieve its desired goals of a mutually beneficial partnership with African countries so long as policymakers continue to view the continent through a narrow, security-focused lens that views elite engagement as the only pathway to influencing a country’s trajectory. Furthermore, repairing the relationship between the United States and ordinary Africans will take more than no longer viewing the continent simply as an extension of the global competition between the United States, Russia, and China. Africans are not simply pawns in some kind of geostrategic chess game but real people with real hopes, dreams, and desires that are no different from everyday Americans’.

Therefore, in order to move forward, the U.S. will need to first take a step back and review its policy towards the continent, as the past decade’s strategy failed to deliver real results for Africans or the United States. While the Biden administration’s U.S. Strategy Toward Sub-Saharan Africa contains a number of promising ideas, such as its focus on conservation, climate adaptation, and a just energy transition, U.S. strategy needs a more fundamental rework of its relationship with the continent’s leaders to truly deliver for both Americans and Africans. What is required instead is an acknowledgement that too often, U.S. rhetoric about development and the commercial relationship with African countries takes a backseat to Washington’s security-related concerns—such as was the case when the U.S. drafted its sanctions on Russia seemingly without the involvement of major African countries, drawing the ire of leaders such as South Africa’s Cyril Ramaphosa. As long as that continues, certain unscrupulous African leaders and militaries are going to use that focus in order to obtain the equipment and training they need to dominate their fellow citizens.

What the U.S. must recognize is that insecurity emanating from the continent is overwhelmingly caused by poor governance and corruption at various levels of government in many countries. As such, until the overarching U.S. strategy towards the continent is reconfigured so that it focuses on partners’ delivery of services and good governance for its citizens, no amount of support for “sustainable development and resilience”, driving the digital transformation, or investing in climate resiliency will matter, as either the funds will be siphoned off by grafting governmental and business elites or Africans will not have their say in the distribution of the proceeds from such investment, as autocrats stifle their voices at the ballot box.

A U.S. strategy that strongly commits to cutting off security assistance to African autocrats and strongmen, no matter the current U.S. security priority in the region, will not only send a message to Africans that the United States is seriously about their ultimate well-being, but it will likely do a much better job in combating the underlying drivers of instability on the continent in the first place. What’s more, pursuing development with a view towards how each investment will impact ordinary Africans—not just on a macro, infrastructural level—in the one year, five year, and ten year timeframes.

Additionally, the U.S. must also do more to understand its disproportionate historical contribution to carbon emissions—with the U.S. responsible for just under ¼ of all CO2 emissions in history—and begin to compensate African partners for the damages caused by rising temperatures. Finally, the United States must stop seeing African countries as merely pawns in the global war on terror or the great power competition with Russia and China, and recognize the growing necessity to make difficult choices when it comes to security cooperation with partners that commit human rights abuses, such as Sudan during the Obama and Trump administrations or the government of Abiy Ahmed in Ethiopia.

Pursuing such a strategy is, clearly, the more difficult of the options currently available, as it will likely require—at least for a time—reducing the number of “partner” countries the U.S. engages with, and will require constant monitoring and evaluation of those continuing partnerships to see if they are truly delivering for their citizens, as well as Americans. Furthermore, a reconfigured U.S. policy in Africa would also require incorporating a wider range of African voices in program development, including local NGOs, civil society, as well tribal and religious leaders to ensure that the needs of Africans at the local level are being satisfied by any bilateral cooperation.

However, in the long-term, such a new way of dealing with African partners would not only help improve the economic and social outcomes for ordinary Africans, but, by making clear that the U.S. will not support leaders who take advantage of their fellow citizens, it will remove some of the long-term underlying drivers of instability that have been plaguing the continent. Moreover, an Africans-centered foreign policy which delivers real dividends for African citizens would have the added benefit of convincing even larger swathes of Africans that the American model is superior to the Chinese or Russian one, ultimately aiding the U.S. in its great power competition with those countries.

Pursuing a strategy of doing the right thing towards Africans and bringing their needs to the fore when partnering with African policymakers may be the longer, harder road to travel, but it will be the one that is most rewarding for both Africans and their American partners. In time, not only will such a reconfigured relationship provide economic benefits for Africans, but it will further open up an export market that will be home to the largest segment of the human population in thirty years, benefitting Americans, as well. Finally, a more altruistic American foreign policy towards Africa will likely be remembered by the citizens in partner countries, who will hopefully recognize the U.S.’ shift from paternal, neo-colonialist behavior to finally treating Africans as they deserve to be treated: as equal partners in a mutually beneficial relationship.