February 3, 2023

In August of 2021, as the U.S. military was completing its withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan, a U.S. MQ-9 Reaper drone, using Hellfire missiles, destroyed a vehicle driving near Hamid Karzai International Airport that the Department of Defense initially said was laden with explosives. However, despite weeks of insisting that the strike was conducted against a legitimate enemy target, the U.S. was forced to launch an investigation into the incident after the New York Times published the results of their own visual investigation which challenged the military’s assertion that the vehicle posed a threat to U.S. forces. Despite the Times report, however, and even after Defense Secretary Austin on September 17th, 2021 directed a review into the strikes to determine who should be held accountable and the, “degree to which strike authorities, procedures and processes need to be altered in the future,” nearly a month later, victim Zemari Ahmadi’s brother said that he had not been contacted by the U.S. government to either apologize or offer solatia or condolence payments. Moreover, following the conclusion of the Department’s investigation, it was revealed that none of the military personnel involved in the failed drone strike would face any kind of punishment for their mistakes.

Sadly, the strike in Kabul was not simply an isolated incident, but merely part of a pattern of U.S. behavior in conflicts around the world where the knee-jerk reaction by DOD officials regarding allegations of civilian harm caused by U.S. operations is to circle the wagons and deflect criticism and blame for faulty targeting or decision-making while shielding wrongdoers from meaningful repercussions. Moreover, the Department of Defense’s reflexive refusal to provide compensation or even apologize to victims—despite eventually providing an undisclosed sum to Ahmadi’s family at some point months later—demonstrates a troubling pattern of behavior from all levels of the military chain of command and speaks to issues in investigating and responding to incidents of civilian harm. As Steven Kwon, the founder and president of Nutrition & Education International—the California-based aid organization that employed Zemari Ahmadi—said to the Times that, the DOD’s, “decision is shocking,” and that, “how can our military wrongly take the lives of 10 precious Afghan people and hold no one accountable in any way.” Unfortunately, as Mr. Kwon will have likely discovered, this is sadly how the United States Department of Defense often behaves in the various armed conflicts it participates in around the globe.

Indeed, in late December of 2021, the New York Times published a rather shocking exposé outlining the failures of the American air war in the Middle East from 2014-2018. The piece, its author Azmat Khan wrote, “lays bare how the air war has been marked by deeply flawed intelligence, rushed and often imprecise targeting, and the deaths of thousands of civilians, many of them children, a sharp contrast to the American government’s image of war waged by all-seeing drones and precision bombs.” Moreover, Khan’s Times report documents how incidents of alleged U.S-caused civilian harm were routinely highlighted by slipshod pre-strike processes and an overall culture of impunity that failed to: detect civilians, investigate incidents on the ground when they occurred, identify lessons learned after the fact, or discipline those who were responsible for the tragedies in the first place. More disturbingly, the Times report suggests a military that simply wants to look the other way when it comes to alleged incidents of civilian harm that occur during its operations. Such a situation is both morally indefensible and strategically untenable. The U.S. can, should, and must do better in transparently and credibly investigating alleged incidents of civilian harm caused by U.S. forces.

The Detrimental Effects of U.S.-Caused Civilian Harm

The United States has known for years that the harm done to civilians from its military operations would have a deleterious effect on relationships with the populace. To that end, the Open Society Foundation’s Christopher D. Kolenda, Rachel Reid, Chris Rogers, and Marte Retzius wrote in a 2016 report, “The Strategic Costs of Civilian Harm: Applying Lessons from Afghanistan to Current and Future Conflicts,” that U.S.-caused civilian harm had, “severely undermined the legitimacy of the international mission and as its partner and ally, the legitimacy of the Afghan government.” Kolenda et al. further noted that in Afghanistan, “civilian harm was easily exploited by the Taliban,” as, “Taliban publications, public communications and propaganda routinely made use of incidents of civilian harm to paint U.S. forces as an indiscriminate, anti-Muslim occupation force.” Despite the fact that these Taliban allegations were often overblown or exaggerated, the civilian casualty incidents that did occur were frequent and widespread enough to lend credibility to such a propaganda campaign in the first place.

Ultimately, while the Department of Defense (DOD) is endeavoring to reform its civilian harm mitigation and response efforts, the 2021 Times report does indicate that there are certain problems which are not likely to be solved through efforts such as more robust data management platforms, especially as the recently released Department of Defense Civilian Harm Mitigation Response Action Plan (CHMR-AP) does little to address issues relating to the independence and impartiality of the individuals investigating alleged incidents. Furthermore, until the forthcoming DOD Instruction on Civilian Harm Mitigation and Response is published later this year, the CHMR-AP is merely more of a list of desired improvements than a real path towards mitigating future civilian casualties in U.S. and partnered military operations.

Whenever the DOD Instruction does emerge later this year, it must come with better procedures regarding the investigation into possible incidents of civilian harm or violations of international humanitarian law in armed conflict, with a special emphasis on the frameworks required to address questions of independence and impartiality regarding the military and civilian individuals tasked with looking into such alleged incidents. Moreover, in its quest to more adequately address future incidents of alleged civilian harm, the Defense Department must not forget to address prior cases where the DOD has received credible reports of civilian casualties—an issue that Senator Elizabeth Warren and Congresswoman Sara Jacobs recently highlighted in a December 19, 2022 letter to Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin—making more frequent use of the $3 million per year that Congress has set aside for ex gratia payments to redress victims of injury and loss as part of the 2020 National Defense Authorization Act.

As Army Techniques Publication 3-7.06, Protection of Civilians, notes, “protection of civilians is important for moral, political, legal, and military reasons and must be addressed during unified land operations regardless of the primary mission.” Therefore, if the Department does not do more to address these issues, there is not only a risk that it will foster a culture of impunity amongst troops in the field and those making targeting decisions at headquarters, but it could pose real strategic concerns for future counter-insurgency operations, especially as, “studies show that counter-insurgencies fail when an insurgency has sustainable internal and external support, or a host nation government loses legitimacy,” and that, “civilian harm tends to accelerate both problems—it is like burning a candle at both ends with a blowtorch.”

Challenges in Investigating Alleged Incidents of Civilian Harm

In light of these facts, it is important to take a look at some of the key issues related to investigations into alleged U.S.-caused civilian harm in armed conflict, especially as the U.S. continues to develop an over-the-horizon counterterrorism capability that have resulted in an increase in strikes conducted by unmanned American vehicles, whose operation can still be incredibly dangerous for civilians.

Helpfully, the Center for Civilians in Conflict (CIVIC) recently published a primer on “Investigations into Civilian Harm in Armed Conflict,” prepared by Claire Simmons as part of a partnership between CIVIC and the Essex University Crisis and Conflict Hub, which aims to identify challenges related to investigations into possible incidents of civilian harm and provides key recommendation for U.S. decision makers in ensuring that effective investigations into those incidents are subsequently carried out.

As Simmons points out, in addition to often being politically and strategically necessary, “States have an international legal obligation to conduct investigations into severe violations of international humanitarian law (IHL) and international human rights law,” and that, if they do not do so, other States may prosecute members of their armed forces under the principle of universal jurisdiction or through some kind of international criminal tribunal like the International Court of Justice. Moreover, Simmons notes, States also have, “an established obligation to conduct some form of effective investigation into other possible violations of international humanitarian law, including those that may have caused civilian harm.”

However, in conducting these investigations, nations often run into a number of challenges which impede their overall effectiveness, and which often leave victims and their next-of-kin wondering if they’ve simply been further mistreated. More specifically, though, Simmons’ recent CIVIC paper outlines five key issues that States often face when conducting investigations into alleged incidents of civilian harm, beginning with the credibility of the allegations being made against the armed force involved. Here, she notes that the credibility of an allegation will always depend on the specific context involved. However, she also points out that the particular individual alleging that harm happened, the level of detail that they provide in making their claim, and the corroboration provided by other sources, will all ultimately determine whether an alleged incident of civilian harm is deemed credible by U.S. decision makers. However, despite Simmons’ admonition that, “States must not rely only on their own information to assess [an] allegations’ credibility,” especially as, “mistakes or inconsistencies in recording operational data may occur, and civilians may bring to the attention of militaries information about operations that they may be unaware of,” it appears that, all too often, that is exactly what happens.

According to one recent RAND Corporation study looking at U.S. military operations from 2015-2017, during that period, “U.S. military officials did not sufficiently engage external sources for information before concluding that reports of civilian casualties were not credible,” choosing instead to rely on, “its own internal data and records [which] are sometimes incomplete.” As a result of this failure to give sufficient weight to external reporting avenues, Human Rights Watch wrote in 2017 that, “the U.S. government’s investigations regularly exclude one of the most important sources of evidence [in witness interviews], and are at odds with international fact-finding vest practice, developed over the past decades by researchers and investigators with human rights NGOs, the United Nations, and international criminal tribunals.”

Another issue that Simmons posits is standing in the way of effective investigations into alleged civilian harm incidents arises when alleged civilian harm incidents occur in difficult-to-reach locales, such as when the U.S. conducts its “over-the-horizon” drone strikes in Pakistan, Somalia, Yemen, and elsewhere. With U.S. operators gathering their intelligence and manning drones hundreds or thousands of miles away from their intended target, “investigations into remote strikes with no personnel on the ground may consist primarily of reviewing pre- and post-strike footage (video or satellite imagery) and reviewing the decision-making process, such as the quality and sources of intelligence used and the analysis of this information.” In the case of these so-called “over-the-horizon” strikes, investigators are often unable to access the strike location and interview possible civilian witnesses on the ground who may corroborate possible civilian harm incidents. While non-governmental or civil society organizations and the media may conduct their own investigations, as seen above, the United States is often unwilling to accept or incorporate external sources of information regarding alleged incidents into its investigations.

Yet another issue that was outlined in Simmons’ piece for CIVIC—and which will be addressed in more detail in a section below—is that military investigations are often seen as insufficiently independent and impartial by victims, their families, and/or their fellow citizens, limiting the investigation’s overall strategic and political value—especially in a counterinsurgency (COIN) environment. To overcome this issue, Simmons’ piece suggests that: military commanders have a role in ensuring that adequate safeguards are set up to ensure there is no conflict of interest between investigators and those being investigated; the complexity of an alleged incident may warrant outside expertise being brought in—for instance in evaluating what effects secondary explosions from U.S. strikes may have had on an alleged victim—to aid the investigation; independent oversight mechanisms—whether through appeals mechanisms, systems of inquiry, review procedures, legislative oversight or ombuds institutions—be established to ensure the accountability of investigators; and that there are simply certain situations where the use of members of the armed forces as investigators may affect the overall perception of justice on the part of the victim and their fellow citizens.

The fourth challenge outlined by Simmons is that frequently, the U.S. is not the only military force operating in an area, with the frequency of partnered and Coalition operations only increasing in recent years. As Brookings Fellow, and former Air Force officer, Sara Kreps told the audience during an April 21, 2022 webinar on Protecting Civilians in Partnered Military Operations for the Brookings Institution, “since the end of the Cold War the United States is not fighting wars on its own. It’s always fighting with local partners, it’s fighting as part of a multilateral operation.” Moreover, in these multinational operations, it is often a challenge not only for victims to decipher which nation it was that actually caused them harm as well as the fact that different States often have different procedures and rules regarding investigations into possible violations as well as amends and reparations processes. As such, Simmons notes, these difficulties may create, “an apparent ‘cloak against accountability’ in which political and military stakeholders feel they have fewer incentives to hold their forces accountable for their actions.”

In investigating and determining the ultimate responsibility for alleged incidents of civilian harm, Simmons argues, States engaging in coalition operations should look to agree on common investigative procedures through their various memoranda of understandings and status of forces agreements with partner countries. The creation of standardized procedures should support common documentation and reporting requirements as well as common thresholds to trigger an investigative review in the first place.

One final barrier to effective investigations of civilian harm incidents in conflict zones that the CIVIC report lists is that States often do not provide enough transparency regarding the details of their investigations, resulting in an opaque process that reduces the legitimacy of investigation reports and undermines the credibility of U.S. military forces in the eyes of victims and their fellow citizens. While Simmons acknowledges that the exact degree of transparency required in an investigation will vary based on the particular context involved in the alleged violation, she does remark that, “the principle of transparency must…serve the overall effectiveness of the investigation and must, among other things, clarify the facts and judicial truths of a situation.” Despite what this principle would seem to require, however, States often impose blanket restrictions regarding information related to investigation on the grounds of national security, often insisting that transparency is not an absolute requirement and that it must be balanced with other, competing interests.

Achieving Transparency, Impartiality, and Justice in Investigations in Armed Conflict

Fundamentally, then, the main tension when it comes to the effective investigation of alleged incidents of civilian harm caused during military operations is between what the military and civilians on the ground see as a “reasonable” investigation into the incident. As Claire Simmons also writes in a different paper for the International Review of the Red Cross, “Whose perception of justice?: Real and perceived challenges to military investigations in armed conflict,” any, “investigations into serious violations of IHL must be effective, and the adequacy of the reasonable measures put into an investigation must be assessed in light of this effectiveness.” However, she also notes that, “one of the biggest causes of contention regarding the effectiveness of any military investigation into possible violations of international law is the matter of independence and impartiality,” as, “it is often perceived that if military personnel investigate a member of the armed forces for alleged (criminal) offenses, this is nothing more than ‘the military investigating itself’, and an expectation exists that a finding of wrongdoing would have no credibility.”

Whether it is in Pakistan, Somalia, Syria, or Yemen, U.S. airstrikes have resulted in the deaths of countless thousands of innocent civilians; and while the Department of Defense will likely claim that almost every single incident of civilians being killed was the result of a mistake or other error, the point remains that the armed forces of the United States has slaughtered far too many innocent non-combatants in the past two decades. Ultimately, the crushing volume of civilian deaths in U.S.-led operations, and the DOD’s stubborn refusal to thoroughly investigate alleged incidents before denying their validity—as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Mark Milley said in the aftermath of the U.S. strike in Kabul that killed Zemari Ahmadi, “the procedures were correctly followed and it was a righteous strike,”—demonstrates why the U.S. military is often not seen as a credible interlocutor in the eyes of victims and their fellow citizens.

Essentially, when combining the U.S. military’s reflexive denial of culpability for civilian harm with the concern that civilians may have regarding military officials investigating the alleged harm caused by their own fellow service members, it can lead to a situation where civilians in the conflict area lose whatever small degree of trust that they have towards the armed forces, undermining the U.S.’ objective to help partner governments win the “hearts and minds” of civilians in counterinsurgency operations, and ultimately hindering the cooperation between the public and the military that is so often needed in even the modern conventional war environment.

As Daniel Mahanty and Sahr Muhammedally write in their paper, “The Human Factor: The Enduring Relevance of Protecting Civilians in Future Wars,” not only does protecting civilians from harm in U.S. military operations help, “to fulfill the government’s public responsibility to protect the moral welfare of those who do the fighting,” but the United States, “learned through its experience in Vietnam that the use of unbridled violence in pursuit of war aims could be as much of a liability as an asset, not only with respect to the limited aims of winning the war, but in preserving the moral welfare of the country itself.”

In examining investigations into civilian harm, it is important to, as Simmons states, look at the, “particular tensions [which] arise with the perception of justice in the context of military judicial procedures, especially surrounding questions such as whether independence is possibly within a chain of command, or how military culture might affect impartiality.” Moreover, “in addition to these challenges, the nature of an armed conflict itself can often lead to aggravated distrust of State institutions, leading to particular difficulties in establishing a perception of justice,” in the country where military operations are ongoing.

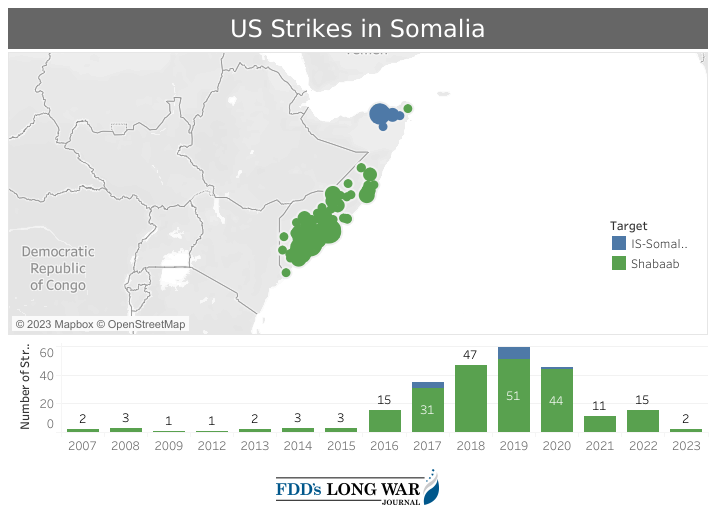

In light of these facts, one way to examine Simmons’ recommendations for achieving the perception of justice in military investigations in armed conflict through the lens of the ongoing U.S. involvement in the fight against Al Shabaab in Somalia, a conflict that has recently seen U.S. troops return to ground operations, and which has already resulted in the killing of one high-ranking ISIS figure in recent days. As Amanda Sperber’s report for the Dutch peace organization PAX, “Is it too much to kill three or four Al Shabaab: Civilian perceptions on Al Shabaab and harm from US airstrikes in Jubbaland, Somalia,” submits, “the impact of [U.S.] airstrikes clearly takes a broad toll on communities across Jubbaland, affecting more than the intended targets alone and frequently resulting in long-term negative effects.”

Despite this being the case, the United States, “has fallen short in providing meaningful response. In situations where [US Africa Command-AFRICOM] has acknowledged civilian harm, it has not communicated this to the victims or relatives thereof, who often had to learn of this through AFRICOM’s civilian casualty assessment reports…Nor have ‘credible’ assessments ever resulted in ex gratia payments to the affected civilians or their families.” As the U.S. is currently operating in Somalia in an attempt to shore up the administration of Hassan Sheikh Mohamud and to, “enable a more effective fight against al Shabaab,” in a seeming continuation of former President Trump’s own approach to the country, the failure to effectively and transparently respond to alleged incidents of civilian harm are particularly harmful to the U.S.’ overall strategic goals in the country.

As the PAX report points out, under the Trump administration, one, “former Somali official described the situation as the US having been given a ‘blank check’ regarding airstrikes,” despite the fact that, “as the number of airstrikes increased, so did allegations of civilian casualties and reports of displacement and other civilian harm effects caused by US operations.” Despite these reports, however, there have been credible allegations that U.S. processes for investigating incidents of civilian harm in Somalia often do not satisfy the requirements for independence, impartiality, and effectiveness needed to provide justice for victims and their families.

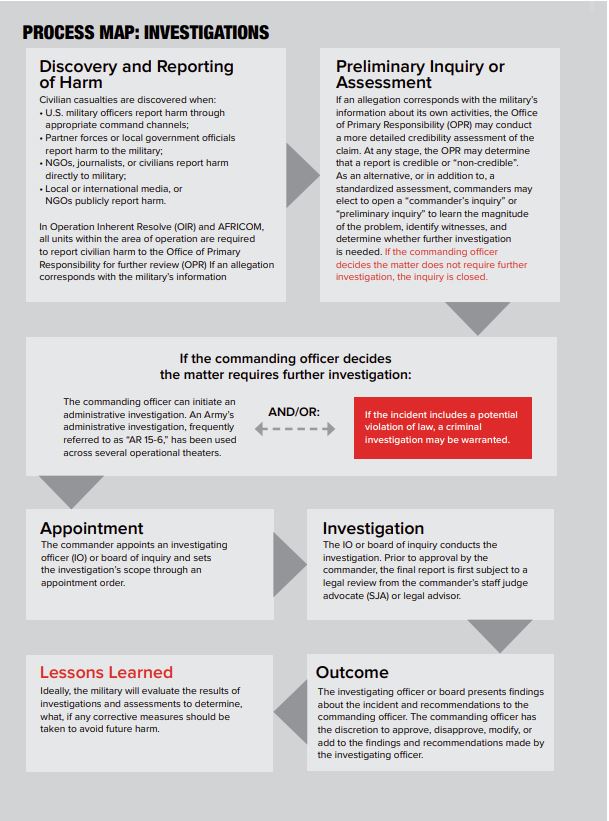

In examining the problems regarding the U.S. response to alleged cases of civilian harm caused by U.S. forces in Somalia, the PAX begins with a description of the investigative process from the point of view of AFRICOM. At first, the combatant command conducts an assessment to verify whether the date and location of an incident corresponds to instances of U.S. action in the area. If this is determined to be the case, the command then completes a Civilian Casualty Assessment Report which, “contains information about the incident, as well as documentation supporting its conclusions, such as full motion video.” The combatant command then comes to a conclusion, based on its own internal review, of whether an allegation is “credible”—meaning more likely than not that civilian deaths or injuries were caused as a result of U.S. military action—and publishes its determination on its website.

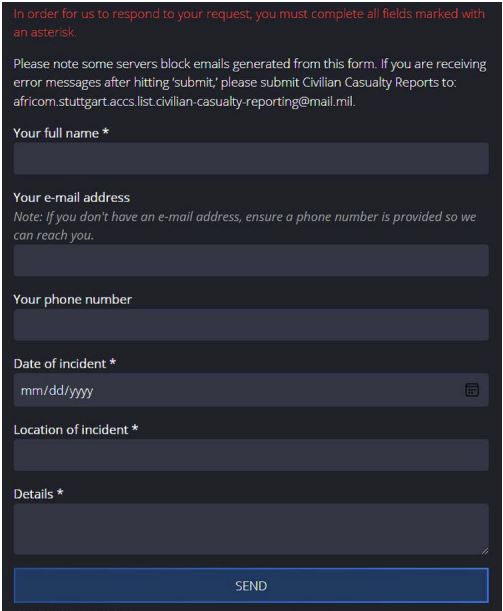

However, as the PAX report notes, “researchers and civil society organizations have, over the years, identified several flaws and limitations in this system, not only in relation to AFRICOM but also with regards to US military practice overall.” The report notes—and a recent RAND Corporation report has also concluded—that human remains buried in the rubble of a building struck by an airstrike would often remain undetected from overhead video surveillance. Moreover, AFRICOM’s assessment procedure does not require its personnel to consult with non-military sources during their investigation, with the result that key data points may be overlooked. The report also notes that civil society activists have expressed frustration over the poor state of direct communications channels between AFRICOM and civil society organizations on the ground, with existing channels suffering from the key flaw that the main way to submit allegations of civilian harm caused by U.S. operations is through a web portal in a country with a a total Internet penetration rate of just 13.7%. Finally, Sperber notes that, “PAX research on this topic indicated that several Somalis who managed to use the system had not heard back from AFRICOM, receiving neither answers, acknowledgement, nor reparations,” in response to their allegations of some harm having been done.

It can therefore be said that AFRICOM’s investigatory processes in Somalia run into the second, third, and fifth issues covered in the CIVIC report on investigations into civilian harm in armed conflict. Moreover, AFRICOM struggles with what Simmons calls the five general principles that are recognized as contributing towards the effectiveness of investigations: independence, impartiality, thoroughness, promptness and transparency.

What’s more, even if AFRICOM were to improve its civilian harm reporting mechanisms through implementation of all of the methods recommended by PAX, including: the creation of a standalone, Somali-language civilian harm reporting web portal; establishment of a dedicated telephone line for reporting allegations of civilian harm caused by U.S. military actions; the leasing of physical office space—not only in Mogadishu but in areas around the country accessible to ordinary Somalis—where citizens can report incidents of civilian harm; or by enabling reports through trusted intermediaries like certain humanitarian organizations or Somali government representatives; it would still not be enough to alter the perception of civilians on the ground. In that event, decision makers would still likely be confronted with the perception that in conducting its own investigations, AFRICOM is merely the fox guarding the henhouse, undermining Somalis overall perception of whether justice has been provided to those that have been harmed.

Impartiality and Independence in Internal Military Investigations

As Simmons points out in Whose perception of justice, there are two main elements most relevant to concerns of impartiality and independence in military investigations into alleged incidents of civilian harm: the military hierarchy and the overall culture of the military. When it comes to military hierarchy, Simmons argues that while, “an impartial investigator is expected to be able to make decisions related to the investigation (for example, in the collection of evidence) based solely upon the relevant facts of the case and the law or regulations applicable to the investigation procedures,” that, “disciplinary or administrative powers,” including the power to promote or demote another member of the military, “may lead them to consciously or unconsciously take into account whether their superior will approve or disapprove of the investigative decisions being made.” This can result in a situation where it is difficult for a junior officer to make a determination of U.S.-caused civilian harm if that officer feels that her superiors have an active interest in the determination that any civilian harm—if it was caused by an outside force—did not come from U.S. forces.

Yet another area where issues of impartiality and independence exist is in the overall cultures of military forces, where, as author Mark Bowden once chronicled, soldiers in the head of battle think thoughts such as: “all that did matter were his buddies, his brothers, that they not get hurt, that they not get killed. These men around him, some of whom he had only known for mothers, were more important to him than life itself.” As Simmons writes, “in a similar fashion to investigations into police misconduct, there is an assumption that there are factors within military life and military culture which will affect the impartiality of investigators, regardless of any structural guarantees of independence that may be in place.”

Indeed, Simmons notes, “the argument posited by some observers suggests that military personnel will necessarily seek to protect the personal interests of other military personnel out of a sense of institutional loyalty, beyond the interest of justice,” and that a sense of “toxic loyalty” amongst military personnel, “may lead to a ‘wall of silence’, a closing of ranks’ or ‘selective memory loss’ by military personnel in the face of investigators, as members of a unit may believe that ethically, and perhaps even militarily, the right thing to do is cover up for misconduct by their peers.”

While Simmons acknowledges that the issue may not be solved only though replacing the military investigator with a civilian one—as civilians may hold a “toxic loyalty” to their own “side” in a conflict, refusing to see the actions of their own country’s military as unjustified—she does concede that, “there are…specificities unique to military institutions which can raise concerns with regard to these institutions’ ability to carry out effective investigations.”

To address issues of toxic loyalty that might hinder effective and impartial investigations into alleged incidents of civilian harm, Simmons argues that it requires, “shaping adequate leadership within the armed forces, as well as appropriate training and effective sanctions of problematic behavior in order to ensure that the ‘right type’ of loyalty and values are upheld in the conduct of military operations.”

Real-World Barriers to Impartiality and Independence in Internally-Led Investigations

Here, however, Simmons’ analysis may risk becoming a victim of wishful thinking, as evidence from the civilian policing world has shown that “adequate leadership” as well as “effective sanctions of problematic behavior” are both often hard, if not impossible, to find, as the overall culture of policing—or, in this case, the military—often inhibits States from putting in place the type of people that would provide the type of leadership that could ensure that that the rank-and-file have the “right type” of loyalty and values. For instance, in June of 2019 in New York City, the City Department of Investigation’s Office of the Inspector General of the New York City Police Department (OIG-NYPD) released its findings into an examination of how the NYPD investigates and tracks complaints of biased policing against its officers. In the report, the OIG-NYPD reviewed 596 cases concerning 888 alleged instances of biased policing and, “NYPD officials confirmed in June 2019 that the Department has never substantiated an allegation of biased policing since it began using this complaint category in 2014.” While the OIG-NYPD report did acknowledge that, “low substantiation rates for biased policing complaints exist in other large U.S. cities, NYPD’s zero substantiation rate stands out.”

Often, the main problem hindering effective internal investigations of military—or police—wrongdoing emanates from the very top, as the military and police are frequently the only government agencies given the ability to truly make autonomous decisions. John Keane and Peter Bell in, “Ethics and police management: The impact of leadership style on misconduct by senior police leaders in the United Kingdom (UK) and Australia,” remark that previous research has, “observed that there are arguably few agency executive positions in government that possess the amount of discretion and autonomy given to police chiefs,” and that a 1998 survey of leaders of police departments from around the world found that most of the ones surveyed fit into a, “Machiavellian framework” where, “the Machiavellian leaders reported themselves to possess manipulative personality traits with a means-end management philosophy, that is to say, the means are justified by the ends.”

Meanwhile, in their paper, “Principals with Agency: Assessing Civilian Deference to the Military,” authors Alice Hunt Friend and Sharon K. Weiner argue that, in the United States at least, “many practitioners [of civil-military relations], however, particularly those in uniform, tend to fret…about excessive civilian control,” as, “recurring debates about civilian ‘micromanagement’ of the military pivot on the assumption that the military ought to have an irreducible degree of autonomy from civilians,” with the result that a civilian overreliance on military expertise gives military actors the opportunity to hide information or problems from the appropriate oversight bodies, as military decision makers feel that their monopoly on the expertise regarding combat operations gives them the right to, “engineer the direction it prefers to receive from the civilian leadership.” In that way, military decision makers are even further insulated from civilian oversight, giving them even less of an incentive to look inwards at possibly problematic behavior from their fellow soldiers.

This insulation from real civilian control can be more clearly seen in the U.S. military’s epidemic of military sexual assault, where, a 2021 New York Times feature chronicles, “for decades, sexual assault and harassment have festered through the ranks of the armed forces with military leaders repeatedly promising reform and then failing to live up to those promises.” The Times report argues that, “one key reason troops who are assaulted rarely see justice is the way in which such crimes are investigated,” as, “under the Uniform Code of Military Justice, military commanders decide whether to investigate and pursue legal action.” Meanwhile, the Pentagon has “vehemently opposed” efforts by legislators like New York Senator Kirsten Gillibrand who has introduced legislation to put the decision to prosecute major military crimes into the hands of independent prosecutors.

If military commanders are willing to look the other way when it comes to investigating allegations of crimes committed against their own female soldiers, it does not require an enormous leap of the imagination to speculate that these same commanders may not want to investigate possible allegations of civilian harm caused by their fellow soldiers, especially as military forces too often dehumanize enemy forces in a way that ends up distorting soldiers’ views on even the civilians in the countries that they are fighting to protect.

As U.S. Army Lieutenant Colonels Peter Fromm, Douglas Pryer, and Kevin Cutright write in their piece, “The Myths We Soldiers Tell Ourselves: and the Harm These Myths Do,” for, “the soldier at war, objectifying oneself as superior and the ‘other’ as inferior can rapidly transform even minor abuses into very serious crimes.” Fromm et al. continue that compounding the problem of “othering” the enemy, “is another delusion— the belief of leaders that such dehumanization can be controlled, noting how, “at places like Bagram, Abu Ghraib, Mosul, and al Qaim, relatively minor detainee abuse turned into horrific crimes that shocked the world.” Moreover, they state that despite the U.S. military opening hundreds of investigations into allegations of detainee abuse, “even in those cases where investigators found criminal negligence, military commanders consistently chose not to punish wrongdoers,” despite strong anecdotal evidence suggesting that the number of crimes reported was only the proverbial tip of the iceberg in terms of the actual scale of detainee abuse.

Fromm, Pryer, and Cutright also point to the rather shocking results of the Mental Health Advisory Teams in Iraq and Afghanistan whose 2006 survey of service members found that, “only 47 percent of soldiers and 38 percent of marines agreed that noncombatants should be treated with dignity and respect,” with, “more than one-third of all soldiers and marines [reporting] that torture should be allowed to save the life of a fellow soldier or marine,” and, “less of half of marines [saying] they would report a team member for unethical behavior.” Similarly distressing is the result of a 2013 Department of Defense Legal Policy Board report, which discovered that, “evidence exists that Service members are at the point of contact or their leaders have been reluctant to inform the command of reportable incidents [of civilian harm],” and that, “this reluctance may be attributed to any number of potential factors including a feeling of justification in connection with actions taken, fear of career repercussions, loyalty to fellow Service members or the unit, or ignorance,” with the result that, “one survey of Marines and soldiers in Iraq reported that only 40% of Marines and 55% of soldiers indicated they would report a unit member for injuring or killing an innocent non-combatant.”

Further demonstrating this troubling perception of the relative value of non-combatants compared to that of their fellow soldiers are the actions of some elite U.S. units such as the Delta-force manned Talon Anvil in Syria, which, according to a December 2021 report by the New York Times’ Dave Philipps, Eric Schmitt, and Mark Mazetti, “launched tens of thousands of bombs and missiles against the Islamic State in Syria, but in the process…the shadowy force sidestepped safeguards and repeatedly killed civilians, according to multiple current and former military and intelligence officials.” The result of which was, despite growing evidence that the unit was recklessly responsible for a growing number of civilian casualties, a former Air Force intelligence officer told the Times reporters that, “leaders seemed reluctant to scrutinize a strike cell that was driving the offensive on the battlefield.”

Specifically, in the case of the Talon Anvil operators, the Times reports that, under pressure to protect allied ground troops and advance the U.S.’ stalled offensive, the unit began to claim that nearly every strike that they called in was in self-defense, enabling them to get easier and more rapid approval for airstrike requests from top Generals, despite the sped up process resulting in, “less time to gather intelligence and sort enemy fighters from civilians,” even as, “a senior military official with direct knowledge of the task force said that what counted as an ‘imminent threat’ was extremely subjective and Talon Anvil’s senior Delta operators were given broad authority to launch defensive strikes,” leading to strikes that harmed civilians.

This broadly permissive environment ended up having a deleterious and catastrophic impact on task force members’ objectivity and even humanity, as Philipps et al. discuss a, “former Air Force intelligence officer [who] said he saw so many civilian deaths as a result of Talon Anvil’s tactics citing self-defense that he eventually grew jaded and accepted them as part of the job.” Moreover, this problem extended far beyond just Talon Anvil operators, as another Times piece from Philipps and Schmitt from November 2021 noted how that while classified special operations unit Task Force 9, “typically played only an advisory role in Syria…by late 2018, about 80 percent of all airstrikes it was calling in claimed self-defense, according to an Air Force office who reviewed the strikes,” as the units’ Delta Operators and soldiers from the 5th Special Forces Group attempted to sidestep the law of armed conflict in ways that resulted in the needless deaths of civilians.

Furthermore, this mis-labeling of strikes as being in self-defense rather than being offensive in nature, and conducted against locations with possible civilian inhabitants, performed an end-run around the U.S. military’s joint targeting process that aimed to incorporate elements of international law—which includes requirements to distinguish combatants from non-combatants, but which can extend the lead time for deliberate target selection and vetting to a minimum of twenty-four hours—but which could hinder the ability of operators to conduct rapid operations against what they feel are legitimate military targets.

As Ben Waldman and Michael Paradis wrote for the Lawfare blog in February of last year, while, “to be sure, the rigor of the joint targeting process can feel like cumbersome and even life-threatening red tape when real-time battlefield conditions require air support,” the, “most dangerous gap in the existing joint targeting process is not that it can be circumvented when the needs of self-defense require. It is that it lacks any disincentive against circumventing its safeguard entirely and routinely by declaring every strike an act of self-defense.”

In that respect, there seems to exist a current in at least some sectors of the U.S. military—and especially the special operations community—that the targeting rules that exist to prevent the needless deaths of civilians merely function as a barrier to their advancement of overall tactical and strategic goals, as well as to the protection of their fellow service members. This is a type of “toxic loyalty” to both the mission and their fellow soldier that has not only led to clear instances of civilian harm, but has seemingly hindered retroactive investigations into alleged instances of harm caused by U.S. forces.

Moreover, as was seen in the aforementioned case of the NYPD—or, for example, the Baltimore Police Department, Los Angeles Police Department, or even the South African Police Service—police forces, especially as they have become more militarized over the years, have encouraged an “us versus them” mindset which has, for the police, damaged relations with the civilian populace and created barriers to effective community policing. This same mindset has enabled militaries, which have historically viewed enemy combatants as “savages” and “barbarians” to further disregard the humanity of those they are fighting to the point where it is difficult for some soldiers to distinguish between a member of a non-state armed group and one of the NSAG members’ fellow countrymen, resulting in a huge number of U.S.-caused civilian casualties in recent years.

Overcoming this mindset will require those investigating alleged incidents of civilian harm not only be exist outside of the chain of command of those they are investigating, but that they have a patina of credibility that demonstrates to potential perpetrators that future investigators will not be overly swayed by personal, service, or unit loyalty while simultaneously conveying to potential victims—and their families and fellow citizens—that the United States is committed to the pursuit of justice and ensuring that the rule of law is upheld.

Justice in Armed Conflict and the Proper Degree of Civilian Oversight of the Military

As David Barno and Nora Bensahel wrote in an excellent 2020 piece for War on the Rocks, more than twenty years of the “War on Terror” has put an enormous amount of strain on the U.S. military in general and on the special operations forces community in particular. The result of which has been that the past few years have seen special operators, “involved in an explosion of very public misconduct and indiscipline cases,” including a Green Beret Major named Mathew Golsteyn murdering an unarmed captive during a 2011 interrogation, Navy SEALs beating bound detainees, and—perhaps most infamously—the case of Navy SEAL Eddie Gallagher who was accused by his own platoon members of shooting civilians and fatally stabbing a captive with a hunting knife. While the high pace of operations over the past twenty years has increased the level of strain on both regular and elite units alike, it is not an excusable explanation for the subsequent rise in civilian harm incidents. However, no matter the cause, the situation is untenable as too often those responsible for malfeasance are not brought to anything even approaching justice.

In Simmons’ Whose perception of justice, the author argues that, “one measure that may be taken to improve the perception of justice is to increase the level of civilian involvement in military justice.” Indeed, what the New York Times’ excellent opinion writer Jamelle Bouie wrote earlier this week in a piece about American policing can also easily be applied to the United States armed forces, in that:

“With great power should come greater responsibility and accountability. The more authority you hold in your hands, the tighter the restraints should be on your wrists. To give power and authority without responsibility or accountability — to give an institution and its agents the right and the ability to do violence without restraint or consequence — is to cultivate the worst qualities imaginable, among them arrogance, sadism and contempt for the lives of others.

It is, in short, to cultivate the attitudes and beliefs and habits of mind that lead too many American police officers to beat and choke and shock and shoot at a moment’s notice, with no regard for either the citizens or the communities we’re told they’re here to serve and protect.”

Just as the U.S. military—and especially its special operations forces soldiers—gives its soldiers a great deal of power over the lives of civilians in their area of operations, it also must demand a concomitant amount of accountability for their actions, lest military leaders and civilian decision makers begin to cultivate a sense of arrogance and contempt for the lives of civilians amongst rank-and-file soldiers. However, such arrogance and contempt for those with less power can already be seen through the pervasive problem of sexual assault against female servicewomen; a problem that got so bad that Congress felt the need to remove military commanders from the position of prosecuting service members for sexual assault in the first place.

Moreover, Congress’ actions on sexual assault is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to rebalancing civilian control of the military. As the 2018 final report of the National Defense Strategy Commission elucidated, the authors came away from their consultations with civilian and military leaders in the Department of Defense—as well as with representatives of other U.S. government departments and agencies, allied diplomats and military officials, and independent experts—with a sense that, “civilian voices were relatively muted on issues at the center of U.S. defense and national security policy, undermining the concept of civilian control.” What’s more, implementing a greater degree of civilian control over issues central to U.S. defense and national security policy—including the protection of civilians in armed conflict and thoroughly and transparently investigating alleged incidents of civilian harm caused by U.S. forces—will be difficult to do with regard to a military that is not looking to accept a greater degree of civilian control and oversight.

Indeed, one merely has to look at the recent writing of Col. Todd Schmidt, Director of the Army University Press at Army University, and particularly his piece for Military Review which demonstrates the recalcitrance of high-ranking military officers when it comes to civilian oversight and their generally poor view of the qualifications of most civilians to oversee the military. As Schmidt argues, “military elites are relied upon to establish, lead, manage, and implement policy that has become ever more militarized and less whole-of-government in its approach. In return, military elites are reportedly disconcerted by the amateurism of their civilian counterparts within the national security process.” While it is likely that civilian leaders have largely brought about this situation by themselves through delegating important national security decisions to military leaders in recent decades, articles like Col. Schmidt’s practically drip with contempt for the ability and intellect of his civilian overseers. Particularly concerning are statements such as:

“…for the military, issues of national security are existential. We have deployed and fought for over twenty years in Iraq and Afghanistan. Our families are committed. Our sons and daughters now increasingly wear the uniform in what has become the ‘family business.’ We are stewards of the military profession. We have a little skin in the game. So, while civilians come and go from government, more concerned with maintaining power than ensuring good governance, the military remains vigilantly engaged, safeguarding the system and the Republic. It is incumbent on those civilians that wish to serve, whether in elected or appointed positions, to be equally, if not more so, qualified, engaged, and committed to duty to country.”

That type of statement, published openly in the annals of the, “Professional Journal of the U.S. Army,” demonstrates a level of contempt for civilian oversight that should be troubling to anyone examining the issue of how to keep human rights and the overall U.S. strategic good at the fore of U.S. armed forces policy and practice. While no one should denigrate the sacrifice and commitment of soldiers like Col. Schmidt—and it truly is easy to sympathize with the argument that he makes—it is highly troubling that he and soldiers like him view their service as somehow entitling them to a greater say in the strategic direction of the country than the democratically elected leaders they report to or the voting public who elects those leaders.

The United States is not some kind of Heinlein-esque fantasy where only those individuals who have donned a uniform are entitled to the right to make decisions for society. Despite this, soldiers like Col. Schmidt would seemingly have you think that the vast majority of our country’s dedicated public servants are mediocrities incapable and unworthy of overseeing the committed professionals in the U.S. armed forces. While this attitude is massively disrespectful to the ranks of brilliant and dedicated professionals working at all levels throughout the country’s national security architecture, it also ignores the concomitant and rather dramatic drop in trust that the majority of Americans have had in the military since the early days of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, as accusations of war crimes and an uptick in military involvement in political matters makes Americans view the armed forces with a renewed degree of skepticism.

As Col. Schmidt’s piece seems to indicate, there seems to be a definite strain of thinking in many sectors of the U.S. armed forces that after more than twenty years of non-stop wars around the world, no one is better positioned than members of the military to dictate their own course. However, nothing could be farther from the truth; and in fact, those years of war and the resultant strain it has put on the American military is exactly the reason why more civilian oversight is required to avoid both military overreach as well as future incidents of civilian harm.

A military that views itself as a people apart from—and even above of—the rest of society is a dangerous combination, and one that can be a recipe for abuse. As Mara Karlin and Alice Hunt Friend wrote for Foreign Policy back in 2018, “to be sure, there is a unique perspective provided by serving in a war zone. But dismissing other perspectives propagates the notion that those in uniform hold a singularly superior understanding of use of force issues.” Moreover, Karlin and Hunt Friend write that, “although combat experience cannot easily be replicated, that does not mean judgment cannot be developed off the battlefield or that civilians are not competent to question operational decisions.”

What’s more, Karlin and Hunt Friend note that the, “idea that civilian politicians are ‘empty barrels’ in contrast to substantive, hardened warriors undergirds the argument that officers and veterans must also fill moral vacuums in strategic leadership—and defy what they deem civilian mistakes when necessary.” They note the writings of U.S. Marine Corps officer Andrew Milburn who argued in 2010 that military members have a, “‘moral autonomy’ that ‘obligates[s] him to disobey an order he deems immoral.’ In his piece, Karlin and Hunt Friend argue, “[Milburn] referred not to questions of an order’s legality but to errors in strategic cost-benefit analysis.” For Karlin and Hunt Friend, “this argument assumes that those in uniform are positioned to make superior political calculations, rather than entertaining the idea that political calculations may be driving the direction politicians give to the military.” Finally, they conclude that, “the uses and ethical limits of power are not something the American people should rely on military professionals alone to define and defend, unless wider social influence over the use of force is no longer a goal of U.S. democracy.”

Whether it is the strike in Kabul that killed Zemari Ahmadi, the staggering amount of civilians dead in Raqqa, Syria, or civilian deaths from U.S. drone strikes in Jubbaland, Somalia, it is abundantly clear that the U.S. military has frequently proven either unwilling or incapable of adequately addressing incidences of civilian harm in such a way that fundamentally reduces the number of civilian harm incidents and prevents them from occurring in the first place. While the Department of Defense’s August 2022 Civilian Harm Mitigation and Response Action Plan is certainly a step in the right direction, it is currently too vague in terms of the specific structures that will be created to investigate alleged incidents of civilian harm as well as the role of civilian personnel in conducting such investigations to be truly transformational.

It is simply not enough to “establish Department-wide procedures for assessing and investigating civilian harm resulting from operations,” if the people doing the investigating are in any way likely to cover up the results of the investigation. As Claire Simmons submits in Whose perception of justice, “assessing who is best placed to carry out an effective investigation requires determining the purpose of the investigation. If the purpose goes beyond criminal accountability and traditional legal adjudication, but rather might involve the dissemination of truth and the recording of different accounts by those involved, the answer to the question ‘who can most effectively investigate?’ may well change and may involve a greater variety of actors from civil society.” However, she notes that the perception of justice in such cases can be hard to achieve, especially in cases where victims, “do not perceive the justice system as independent, impartial or generally just.”

In cases where members of the armed forces are the only individuals conducting an investigation into alleged wrongdoing by their fellow members of the military, it may be impossible to establish a perception of justice amongst the aggrieved, whether or not those conducting the investigation truly believe themselves to be acting in an impartial manner. As the old saying goes, “Caesar’s wife must be beyond suspicion,”; similarly, so must the United States armed forces if they wish to have any credibility amongst the populations that they are working amongst in both current and future conflicts.

While, under international law, Simmons notes, “States may still legally use military justice systems in various situations, including to investigate possible violations of IHL,” there are real-world implications to allowing the proverbial fox to investigate an alleged death in the henhouse. While the service member in this case is likely well trained, and may even have a genuine moral commitment to ensuring that justice comes to even their fellow soldiers, if military-led and -run investigations into alleged civilian harm come back with the verdict that no one in uniform bears any responsibility for the harm, it will likely prove impossible to convince the victims family or many of their fellow citizens that the investigation was truly impartial and independent.

Simmons finishes her paper stating that, “fair scrutiny of military investigations into possible violations of IHL requires considering how military institutions can carry out effective investigations with adequate structural safeguards and due diligence measures in order to mitigate challenges that are likely to arise in military contexts.” Moreover, while she is probably correct that, “as long as armed conflicts exist, it is likely that military bodies will have a role in judicial proceedings involving their personnel,” it is incumbent on political decision makers to ensure that these investigatory processes are structured in such a way that they get at the truth of the incident in question. The United States certainly does not have any interest in exposing members of its armed forces to unnecessary legal jeopardy for their necessary actions during wartime. However, especially when it comes to counterinsurgency operations like those ongoing in Somalia, both do retain a strong interest in ensuring that violations of international law and harm to civilians are investigated thoroughly, with offenders brought to account for their crimes.

Civilian Review Boards for Civilian Harm Incidents

A more transparent and impartial process, therefore, would require greater civilian oversight at all stages of the process, from the recording of incidents to their investigation and ultimate resolution, as there are both real and perceived issues of impartiality and independence when it comes to members of the military investigating their fellow service members. To that end, the creation of an effective, expert civilian review board process would best ensure that members of the military are held accountable for their actions in a conflict area. While such a review board would obviously run into some of the same difficulties that military investigators have when it comes to investigating incidents where the U.S. has little or no access beyond surveillance footage, it could help with assessing the credibility of allegations made by locals, as well as increase both the independence and transparency of the resulting investigations.

As former Executive Director of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of New Jersey, Udi Ofer, wrote in 2016 about police investigations into alleged police wrongdoing, “having police officers police themselves presents obvious conflicts of interest, while having civilians conduct these investigations provides an external check on the police.” While police and armed forces are not entirely analogous—as the military has a stricter code of conduct and disciplinary process under the Uniform Code of Military Justice—they are similar in that they are both armed agents of the state with license to use deadly force when they feel it is justified.

To paraphrase what Ofer writes in his paper on the need for greater civilian oversight of the police, there is a need to hold service members accountable for the unjustified use of deadly force against civilians. Moreover, there is a need for the establishment of units within existing agencies, that are charged with reviewing patterns in military practices that may reveal broader problems relating to civilian harm.

While civilian complaint review boards have existed since the 1940s in the United States, a frequent knock on them has been that they have largely been ineffectual and unable to actually hold police officers accountable for their alleged misconduct. However, one of the biggest challenges to these boards’ ability to perform their functions is their limited authority, which, “creates barriers to their ability to obtain necessary information and conduct independent investigations because they lack the power to compel officer testimony,” and they often lack subpoena power. Indeed, as the Council on Criminal Justice’s Task Force on Policing further noted in April 2021, “even boards that have investigative roles are not well equipped to serve in that capacity because their members do not always have appropriate training or expertise.”

An effective civilian review board for alleged incidents of civilian harm caused by the U.S. armed forces would likely require many of the same elements that Udi Ofer outlines in his evaluation of the elements of effective civilian review boards. The first element of a successful Department of Defense-based civilian review board for alleged civilian harm incidents caused by U.S. operations would therefore be for its board members to be nominated by civil society in both the U.S. and on the ground in the conflict zone, with members of the board required to have a good deal of expertise in a field such as law, civil rights, law enforcement, the military, or forensics. While the total number of ex-military members should obviously be limited to a small minority of the board’s total membership, the experience of at least one ex-servicemember would likely be invaluable to the other experts on the panel.

Furthermore, following the model of a strong civilian review board that was proposed in Newark, New Jersey in 2016, a DOD expert civilian review board for each geographic combatant command could be comprised of eleven members, with seven U.S. citizens nominated by civil society and human rights organizations in both the United States and the country in conflict, which are then presented to the Secretary of Defense, who then appoints the remaining review board members subject to the approval of the President.

A civilian review board for civilian harm incidents would also require a broad latitude to investigate complaints of civilian harm, with the ability to investigate not only the deaths of civilians in armed conflict but those attacks that result in “reverberating effects” on civilians, including displacement, loss of livelihood, and stigmatization, with the victim and/or their families able to receive acknowledgement and proper redress for their situations if they are the result of unlawful or negligent action from U.S. service members.

Importantly, the expert civilian review board must have independent investigatory authority, with the power to subpoena witnesses and documents, including internal disciplinary documents relating to involved service members, medical records, surveillance footage, and any other materials relevant to the investigation. However, this is likely to be an area of disagreement between DOD and civilian harm prevention practitioners, as there are likely to be issues of classification involved with reviewing at least some aerial footage of alleged incidents of civilian harm. As efficacy of these boards will likely hinge on their ability to request and review this classified data, the boards will either have to be staffed entirely by individuals able to achieve a high-level security clearance from the DOD or, more likely, will require the statutory creation of a Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court-like body—along with the designation of appropriate amici to inform the court about specific legal or technical issues in certain cases—that can issue rulings on the declassification of documents and other data on a case-by-case basis, adjudicating whether DOD has legitimate interest in classifying the information or whether it can be provided—in redacted or partially-unredacted form—to the review board to enable them to effectively complete their inquiries.

Once the review board’s investigation is complete, the overall effectiveness of the board and its contribution to the overall perception of justice will mean ensuring that discipline sticks, with the findings of the board being binding on the commander involved. Moreover, the appropriate discipline matrix for alleged infractions must be determined before the review board first sits, with soldiers knowing fully, and in advance, what punishments that they might face as a result of the review board process. As Ofer states in his review of civilian review boards, “this formula not only ensures discipline when the civilian review board finds that wrongdoing has occurred, but it also creates transparency and predictability in the process, allowing the public to know ahead of time what type of discipline will be faced for which type of misbehavior,” granting victims a measure of confidence that justice will be done. Just as with the example of the proposed Newark, NJ review board, exceptions to the review board’s findings must be created for when a “clear error” was made in the board’s investigation, with the Secretary of Defense entitled to make final decisions on whether or not the board’s findings are ,”based upon obvious and indisputable errors [which] cannot be supported by any reasonable interpretation of the evidence.” Absent such a clear error, the civilian review board’s findings would be binding on all individuals involved, up to and including the Secretary of Defense.

A civilian review board for alleged incidents of civilian harm would also require its expert members to have the authority to review the underlying policies that led to incidents in the first place. For example, if the board is made aware of a pattern of civilian harm incidents in a particular U.S. military operation or theater, it should have the power to investigate any evidence that the geographic combatant command or individual units are involved in repeated incidents of civilian harm. Such a review would help uncover whether alleged incidents are a result of a poorly designed pre-strike assessment process, the use of certain munitions in populated environments, a command-wide lack of focus on potential civilian harm, or even the negligence of a particular unit or individual. Once the review board has completed their investigation, it should also have the authority to make formal recommendations for policy reforms to the Undersecretary of Defense for Policy, the Secretary of Defense, the National Security Council, and the President, with the findings also published as a report to the public both in the U.S. and the affected country—translated into the appropriate local language, as necessary.

Just as with civilian review boards in municipal situations, a potential Department of Defense Civilian Review Board for Alleged Incidents of Civilian Harm would have to be funded in such a way that makes it secure from political manipulation that might weaken it. As seen with the cases of Chief Petty Officer Eddie Gallagher and Maj. Mathew Golsteyn, punishing alleged perpetrators of civilian harm can be politically unpopular amongst certain segments of the populace. As a result, there may be a temptation on the behalf of politicians to attempt to interfere with the proceedings of the review board by threatening to withdraw funding in the event of a particularly unpopular decision by the board’s members. To insulate the board from such cuts, the board’s budget might be tied to the overall DOD budget or even the budgets for the individual geographic combatant command involved, with the percentage of the department’s budget committed to the review board fixed by law. The percentage must be enough to fully staff the review board, including funds for, “an executive director, investigators, attorneys to prosecute the complaints, and analysts to audit departmental policies and practices,” with the budget also including enough funding for local office space in or near the relevant conflict, travel to and from the sites of alleged incidents, outreach to affected communities and civil society organizations, and training for investigative officers conducting complex investigations.

The review board must also come with due process protections for service members, with those accused of wrongdoing able to contest the allegations as well as the findings of investigators. Moreover, service members and their attorneys must be allowed access to the evidence used against them, be permitted to provide testimony, and to offer responses and defenses to the alleged misconduct. The review board should also have an independent appeals process, with service members retaining their rights as soldiers throughout the entirety of the process.

Finally, the review board must create a process whereby affected civilians can easily file complaints regarding alleged incidents of harm. As mentioned above, PAX’s Erin BijL has argued this requires either making the complaint process easier to find on DOD’s website or setting up a standalone website in the most-used languages of the conflict zone where the U.S. operates, setting up a dedicated phone line where civilians can make complaints of harm caused to them, their families, or their community members, a physical office located in an easily accessible area for local civilians, or through enabling reports to be taken by trusted intermediaries—such as certain civil society organizations or government representatives—and conveyed to the review board.

As Ofer allows in his own conclusion, “building an effective civilian review board is no easy task,” as it requires both public support, a willing government, and the time and resources to make it all work. As a consequence, municipal civilian review boards across the country have been hampered by their lack of power to subpoena or make discipline stick, with the result that they have largely been seen as ineffectual.

Final Thoughts

The mere perception of impropriety and partiality when it comes to incidents of civilian harm can not only undermine overall counterinsurgency strategy, it can fatally damage the essential relationship between the military and the entire civilian populace. While the Department of Defense is still gearing up for great power competition and peer-competitor conflicts, the vast majority of the troops it has currently deployed are operating in contexts where the buy-in of the civilian populace is still key. Moreover, as the Ukrainian experience has demonstrated to both Kyiv and Moscow, Russian atrocities committed against civilians have only strengthened Ukrainians commitment to repel the Russian assault on their homeland and demonstrated the strategic damage that can be caused by harming civilians.

Therefore, the lesson for the United States is that no matter if the conflict is a future counterinsurgency operation or a full-scale great power conflict against a peer-competitor, the importance of preventing and responding to alleged incidents of civilian harm should remain at the forefront of all operational planning and guidance. If civilians are harmed in the course of U.S. operations, there is an enormous risk that the civilian populace could withdraw their support for the campaign, which is always vital in COIN operations and—as Ukraine’s population has demonstrated—may also be critical in a future fight against a peer competitor.

The only way to ensure the buy-in of the civilian populace in the modern war environment—where mistakes can, do, and will happen—is to guarantee that any and all incidents of civilian harm are investigated in an efficient, transparent, and impartial manner. However, the only way to ensure the full impartiality of an investigation into alleged civilian harm committed by members of the U.S. armed forces is to guarantee to the civilian populace that members of the military will not be the ones primarily responsible for investigating alleged harm caused by their fellow Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen, or Marines. .

While an expert-led civilian review board would likely encounter stiff resistance from both high-ranking figures in the military and some segments of the political class, past experience has shown that permitting the military to investigate itself has resulted in substandard results that have had calamitous results for civilian lives and overall U.S. strategy to help win over the population in countries where our troops are supporting local governments and combating non-state armed groups. By handing over the process to civilians—from the initial receipt of allegations to the determination of punishments—it can hopefully result in a more transparent and fair process that will help prevent future incidents from occurring in the first place and secure the buy-in of the civilian population both at home and abroad.

One thought on “Effective, Impartial, and Transparent: The Need for Civilian Review of Alleged Incidents of Civilian Harm in U.S. Military Operations”