Abstract: This paper delves into the urgent need for effective regulation of private military and security companies (PMSCs) in the international community. It highlights the atrocities committed by the Wagner Group in Ukraine, Mali, and other locations, underscoring the gravity of the threat posed by these firms. The paper examines the failures of previous attempts to regulate the industry, emphasizing that the PMSC industry has largely been left to self-regulate over the past two and a half decades. This laissez-faire approach has been driven by short-sighted “national security” concerns and a neoliberal belief in the power of markets to solve all problems. The United States, in particular, has not only failed to advance its own efforts to rein in the industry but has actively impeded international efforts to do so. In light of these challenges, the paper advocates for the establishment of a regulatory framework that strikes a balance between allowing PMSCs to operate and implementing robust controls to govern their conduct. It emphasizes the importance of stricter scrutiny on subcontractors, improved reporting on the export of PMSC services, and the empowerment of regulatory bodies to enhance oversight. By addressing these issues, the paper aims to contribute to the ongoing discourse on regulating PMSCs and mitigating the risks associated with their operations.

June 16, 2023

The Problem

In April of 2022, video and photographic evidence that emerged showing the bodies of dozens of massacred civilians left scattered across the streets of Bucha, Ukraine shocked the world. While not solely responsible for the atrocities committed there, Russia’s Wagner Group, a private military and security company (PMSC) with a hugely checkered past, likely played a significant role in the wanton brutality that Russian forces subjected the Ukrainian town to. More distressingly, the Russian PMSCs’ barbarities in Bucha were not an isolated incident, as Wagner Group has been accused of similar human rights violations and other war crimes not only elsewhere in Ukraine but in Libya, Syria, the Central African Republic, and elsewhere throughout the world. Indeed, just a month later, the firm would be accused of conducting a military operation together with the Malian army in the village of Moura that resulted in the gross human rights violations and the deaths of nearly five hundred Malian civilians.

Wagner Group leadership has evinced similarly little care for the lives of its own troops, and for the war in Ukraine, the PMSC made the decision to recruit, “thousands of inmates from Russian prisons by offering them pardons in exchange for combat tours,” to fight in Donbas, where they were deployed, as described by one Ukrainian battalion commander, Lt. Col. Pavlo, “…like zombies. They used the prisoners like a wall of meat. It didn’t matter how many we killed—they kept coming.”

While the Biden administration has instituted various economic sanctions on the group and its various subsidiaries—including efforts to cut off the firm’s access to advanced Western weapons systems—and has simultaneously stepped up intelligence sharing with African allies in an attempt to dissuade countries on the continent not to engage the Russian security firm’s services, the United States has historically been absent from the regulation of what used to be known as the mercenary industry.

Despite a stream of statements and diplomatic cables from the administration that demonstrate a growing level of concern about, “Wagner’s ability to shape events in countries where the U.S. and its allies hold business and diplomatic relationships,” Western nations’—and particularly the United States’—decades of somnambulance regarding the regulation of groups which have historically been called “mercenaries” has created a situation where a firm like Wagner can operate with relative freedom throughout the world, free to offer their guns to the highest bidder no matter how they trample on the rights of civilians around the globe. Moreover, while the United States is not solely responsible for the dearth of binding international legislation governing the use of mercenaries or private military and security companies, its frequent use of such firms, coupled with its obstruction of efforts to create binding rules for these entities, has created a situation where the only guardrails for the industry are voluntary standards that lack any kind of international enforcement mechanism.

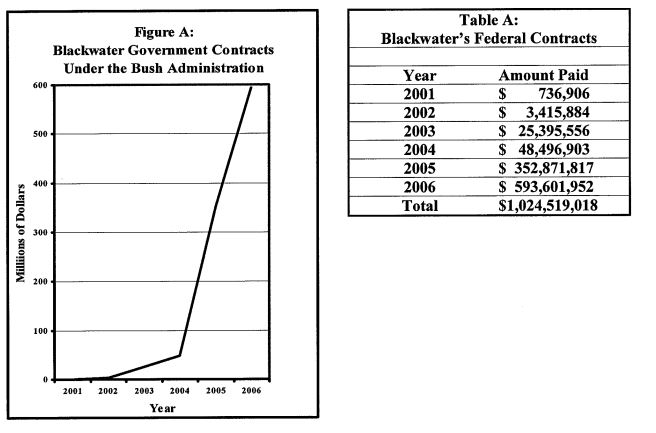

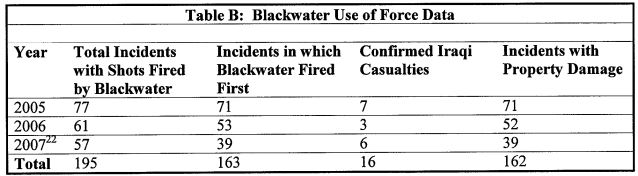

More distressing than the general international silence in response to the barbarities committed by the Wagner Group’s personnel throughout Europe, Africa, and the Middle East in recent years is the similarly lackluster response by the United States towards allegations of human rights violations by its own home-state PMSCs like the one formerly known as Blackwater (now Constellis)—which was involved not only in the Nisour Square massacre in 2007, but had already been accused of repeated instances of excessive force throughout Iraq in the years leading up to the Nisour Square incident.

Especially as the United States attempted to ramp up its own military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan in the post-September 11th period, it looked to the private military and security industry to fulfill the vast amount of logistics, construction, security, and training needs it would face, resulting in a situation where, by 2011, total U.S., foreign, and host country national contractors outnumbered the number of U.S. uniformed military on the ground in those two countries and by 2019, and the ratio of contractor personnel to U.S. troops had reached a staggering 1.5:1. Moreover, this huge expansion in the use of private military and security firms came despite credible allegations against firms like Blackwater and CACI International Inc. of committing human rights violations.

As P.W. Singer notes in his policy paper, “Can’t Win With ‘Em, Can’t Go To War Without ‘Em: Private Military Contractors and Counterinsurgency,” as far back as 2006 in Iraq, “Brigadier General Karl Horst, deputy commander of the US 3rd Infantry Division…tried to keep track of contractor shootings in his sector.” But when, over a period of just two months he found at least twelve shootings resulting in at least six dead Iraqi civilians, Horst said that private military and security contractors often, “run loose in this country and do stupid stuff. There’s no authority over them, so you can’t come down on them hard when they escalate force. They shoot people, and someone else has to deal with the aftermath.”

Singer further raises the point that even when U.S.-contracted PMSC personnel were not behaving badly, their pecuniary interests often led them to engage in behavior that was deleterious to the overall U.S. mission. Specifically, Singer points to the statement of journalist Robert Young Pelton who, describing his time spent embedded with Blackwater contractors in Baghdad, said that, “They’re famous for being very aggressive. They use their machine guns like car horns.” Singer concludes that, “viewed through the corporate lens, where a premium is placed on protecting assets above everything else, this behavior is certainly understandable. But it undermines the broader operation,” noting the statement of former Col. T.X. Hammes who had told PBS’ Frontline that:

“The security forces guarding Ambassador [L. Paul] Bremer. Blackwater’s an extraordinarily professional organization, and they were doing exactly what they were tasked to do: protect the principal. The problem is in protecting the principal they had to be very aggressive, and each time they went out they had to offend locals, forcing them to the side of the road, being overpowering and intimidating, at times running vehicles off the road, making enemies each time they went out. So they were actually getting our contract exactly as we asked them to and at the same time hurting our counterinsurgency effort.”

Similarly, as a 2011 Congressional Research Service report from Moshe Schwartz has argued, “abuses committed by contractors, including contractors working for both DOD and U.S. civilian agencies, can also strengthen anti-American insurgents.” Distressingly, Schwartz points to the statement of one senior Iraqi Interior Ministry official who, when discussing the behavior of private security contractors in his country said that, “Iraqis do not know them as Blackwater or other PSCs but only as Americans.”

Finally, Schwartz stresses that some analysts have seen the harm that unaccountable PMSC contractors can have on U.S. counterinsurgency strategy, arguing that, “if counterinsurgency operations are a competition for legitimacy but the government is allowing armed contractors to operate in the country without the contractors being held accountable for their actions, then the government itself can be viewed as not legitimate in the eyes of the local population.”

According to P.W. Singer, these interactions can be more clearly understood through a hypothetical real-world example:

“An Iraqi is driving in Baghdad, on his way to work. A convoy of black-tinted SUVs comes down the highway at him, driving in his lane, but in the wrong direction. They are honking their horns at the oncoming traffic and firing machine gun bursts into the road in front of any vehicle that gets too close. He veers to the side of the road. As the SUVs drive by, Western-looking men in sunglasses point machine guns at him. Over the course of the day, that Iraqi civilian might tell X people about how ‘The Americans almost killed me today, and all I was doing was trying to get to work.’ Y is the number of other people that convoy ran off the road on its run that day. Z is the number of convoys in Iraq that day. Multiply X times Y times Z times 365 and you have the mathematical equation of how to lose a counterinsurgency within a year.”

Further complicating matters, it is not only States that have increasingly used these types of firms, as Ekaterina Zepnova, Giulia Campisi, Felip Daza, Carlos Díaz and Nora Miralles submit that these firms, “are increasingly used not just to guard elite housing developments, but also in public spaces too,” as, “some majority-Jewish neighbourhoods in Jerusalem, for example, are protected by PMSCs such as Modi’in Ezrachi, which perform roles that could properly be considered to be those of public security forces.” Moreover, the authors point out that, “in some cases, such as Cape Town, where the exercise of public security often continues to reflect the inequalities of the Apartheid era, private security companies such as Professional Protection Alternatives not only patrol wealthy white neighbourhoods but also public areas such as beaches, carrying out operations to evict people from public spaces.”

As Sean McFate articulates in his 2019 monograph, “Mercenaries and War: Understanding Private Armies Today,” in today’s world, “even terrorists hire mercenaries,” noting that, “Malhama Tactical is based in Uzbekistan, and they only work for jihadi extremists,” noting that, “most of [the firm’s] work is in Syria for Nusra Front, an al Qaeda-affiliated terrorist group, and the Turkistan Islamic Party, the Syrian branch of a Uighur extremist group based in China.” What’s more, McFate continues, it is not just extremists like the Turkistan Islamic Party that is reaching out to these firms, as, “nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) such as CARE, Save the Children, CARITAS, and World Vision are increasingly turning to the private sector to protect their people, property, and interests in conflict zones,” as even noted public figures such as, “actress Mia Farrow considered hiring Blackwater to end the genocide in Darfur in 2008.”

Finally, as Raphael Parens has posited, even if the war in Ukraine resolves advantageously for Kyiv and the West, the aftermath of that conflict is likely to bring a surge of mercenaries into Africa as, “thousands of former soldiers with combat experience will hit the open market.” While, he acknowledges that, “these soldiers will find limited job prospects in Ukraine or Russia, as both armies cut down on active-duty troops,” Parens maintains that, “Wagner Group and other private military companies from South Africa, France, and the United Kingdom [will] offer these former soldiers an option to support their families and escape their circumstances,” with, “the consequences…[falling] heavily on African countries, which have already begun to employ mercenaries at a rate not seen since the Cold War.”

In short, while States have failed to grapple with the rise of the PMSC industry over the past two decades, the war in Ukraine presents a unique opportunity to rectify that mistake and to begin to bring this rapidly growing industry more under State supervision.

A Growing Industry

The provision of private military and security forces is a global industry which is projected to grow from $100 billion to $224 billion in 2020 and is expected to reach $457.3 billion by 2030. However, despite its significant expansion in both size and scope since the turn of the century, efforts to regulate this industry have not kept pace.

As the National Defense University’s Sean McFate has argued, “privatizing war changes warfare in dangerous ways,” as when Clausewitz and Adam Smith are merged together the resultant, “for-profit warriors are not bound by political considerations…[individuals whose] main restraint [are] not the laws of war but the laws of economics.” Indeed, one illustrative incident that demonstrates the dangers of PMSC firms placing profit over politics took place in Syria in 2018 when several hundred Wagner fighters attacked a U.S.-manned outpost in Deir ez-Zor in the quest to gain control of petroleum facilities in the country despite the conflict risking a full-scale confrontation between Russia and the United States.

McFate further contends that, “private war lowers the barrier for entry,” into conflicts as “mercenaries are rented forces and clients may be more carefree about going to war if their people do not have to bleed.” Finally, McFate notes that, “private war breeds war,” in that, “mercenaries and clients seek each other out, negotiate prices, and wage war for private gain. This prompts other buyers to do the same in self-defense. As soldiers of fortune flood the market, the price for their services drops and new buyers hire them for additional private wars. This cycle continues until the region is swamped in conflict…”

Ultimately, whether for short-sighted “national security” reasons or due to a neoliberal belief in the power of markets to solve all problems, the PMSC industry has been mostly left to regulate itself over the past two and a half decades, as the United States has not only failed to advance its own efforts to reign in the industry but it has actively impeded international efforts to do so.

This failure to advance more stringent industry regulations not only diminishes U.S. condemnations of the atrocities committed by groups like Wagner but it actively undermines U.S. foreign policy goals in Africa, where the failure to creating binding international regulations on the conduct of such groups has led to the expansion of Russian influence—by way of its proxy, Wagner—throughout countries such as Guinea, Burkina Faso, and Chad where Wagner Group—on behalf of Russia—has offered “counterterrorism” and logistical support to military-led governments that have had to look elsewhere for security assistance after Western leaders had condemned military coups in those countries.

While non-binding instruments such as the Montreux Document (Montreux) and the International Code of Conduct for Private Security Service Providers (ICoC) and its Geneva-based International Code of Conduct for Private Security Service Providers’ Association (ICoCA), do provide some kind of normative guide rails for the industry conduct, neither the Montreux Document nor the ICoC are internationally binding legal instruments, rendering compliance with either the Montreux Document or the ICoC an entirely voluntary processes, with no effective sanctions to provide firms a real incentive not to violate these collections of “good” practices.

Outsourcing State Functions

As Frédéric Mégret writes in, “Are There ‘Inherently Sovereign Functions’ in International Law,” the, “privatization of functions that were previously considered sovereign has reached new heights, accelerating a process of ‘retreat of the state,’” as that privatization process has extended not just to the running of “previously public monopolies, including the health system, education, and even prisons,” but to, “the use of force,” as well, including police, military and spying functions. Mégret further points to a 2018 paper from Nigel D. White, Mary E. Footer, Kerry Senior, Mark van Dorp, Vincent Kiezebrink, Y. Wasi Gede Puraka, and Ayudya Fajri Anzas which argues that, “the prevailing orthodox view of the public-private distinction as found in international law is very much based on the concept of a strong sovereign state, one that retains a firm grip, if not monopoly, on the use of force,” and that international rules governing state responsibility and whether certain conduct is a “public” or “private act for which the state does or does not bear direct responsibility, “are not well-suited to the turn of the century phenomenon of Western governments contracting out security functions to private actors…”

As Nigel D. White writes in his own piece responding to Mégret’s article, the outsourcing of security functions, “reduces the state’s competence on the international plane including its ability to project its sovereign power abroad within the framework of international laws agreed by states on the basis of sovereign equality. By transferring some of its military and security functions to the private sector in its external use of force, the state erodes the power of direct command and control it has over armed forces essential for the state’s monopoly.” White notes that in this shift from public to private force the, “contract-based model largely depends on a combination of liability in private law and self-regulatory forms of corporate social responsibility that purport to ensure that contractors comply with the basic rules on the use of force,” and that, “outsourcing means that a strong vertical system of control over the use of force is replaced by a weaker horizontal one.” However, in practice, this weaker horizontal system of control largely only exists for Western firms, and even then, it is more there to ensure firms’ continued ability to obtain government contracts that require adherence to certain codes of conduct and less about ensuring robust regulation of this emerging—and frequently troubling—global industry.

Moving forward, what the United States needs to do is abandon its laissez-faire attitude towards the industry and embrace its role as a global standards-setter. This can be achieved by actively collaborating with the UN Working Group on Mercenaries to develop a legally binding international agreement that works to constrain the freedom of action of private military and security firms. Such an agreement should ensure proper vetting, training, licensing of PMSC personnel, prohibition on specific weapons in certain situations, and the establishment of mechanisms for victims to obtain full restitution from firms and individuals responsible for harm. Without a legally binding international convention governing the behavior of PMSCs, these firms will continue to proliferate. Consequently, the U.S. will find itself in a world where private firms are free to exert force with relative impunity around the globe, as they are unlikely to face prosecution under existing legislation in host or home nations.

Early Efforts to Regulate the PMSC/Mercenary Industry

Major efforts to regulate the private military and security industry largely arose due to the actions of mercenary outfits in the wars of national liberation in Africa throughout the second half of the twentieth century. Throughout the 1960s, ‘70s, and early ‘80s, the United Nations Security Council had issued several resolutions condemning the use of mercenaries in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1967, the People’s Republic of Benin in 1977, and the Republic of Seychelles in 1981. However, despite voicing its extreme concern about states tolerating the recruitment and training of mercenaries on their territory, the Security Council chose to refrain from taking more binding actions to stop the proliferation of such groups at that time.

While the UN failed to specifically address the proliferation of mercenarism in Africa in the latter half of the twentieth century, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) did demonstrate some level of concern with the industry’s continued rise. Specifically, the 1977 Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions of 1949 contains Article 47, which defines mercenaries as any person who is: a) is specially recruited locally or abroad in order to fight in an armed conflict; b) does, in fact, take a direct part in the hostilities; c) is motivated to take part in the hostilities essentially by the desire for private gain and, in fact, is promised, by or on behalf of a Party to the conflict, material compensation substantially in excess of that promised or paid to combatants of similar ranks and functions in the armed forces of that Party; d) is neither a national of a Party to the conflict nor a resident of territory controlled by a Party to the conflict; e) is not a member of the armed forces of a Party to the conflict; and f) has not been sent by a State which is not a Party to the conflict on official duty as a member of its armed forces.

Unfortunately, in defining a mercenary so precisely—specifically the section requiring that a mercenary be promised “material compensation substantially in excess of that promised or paid to combatants of similar rank and functions in the armed forces of that Party”—the Additional Protocols drew too narrow of a distinction on who can be defined as a mercenary, limiting the Additional Protocol’s effectiveness. For example, as a former member of the UN Working Group on Mercenaries, José L. Gómez del Prado, writes in his article, “The Ineffectiveness of the Current Definition of a ‘Mercenary’ in International Humanitarian and Criminal Law,”’ for the book Public International Law and Human Rights Violations by Private Military and Security Companies, that these definitions would be difficult to actually apply to the private military and security personnel that were so active throughout the United States’ wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Del Prado asserts that, “the majority of people recruited by PMSCs to carry out security activities in the conflicts in Iraq or Afghanistan—people who could have been considered mercenaries—were motivated by a combination of selfish and altruistic motives…which were all in play simultaneously.” As such, he argues that, as human behavior is extremely complex and cannot be reduced to single factors, “it is impossible to prove legally the belief that mercenaries are solely financially motivated,” ultimately limiting the applicability of the Convention’s definition. In light of those limitations, del Prado suggests that, “rather than looking at the necessary prerequisites that set in motion and individual’s motivation, we should be concentrating on the acts taking place and the human rights violations they perpetrate.”

However, the Red Cross was not the only international organization that attempted to restrict the use of mercenaries during this period, as the Organization of African Unity (OAU) Convention for the Elimination of Mercenarism in Africa (OAU Convention) opened for signature in Libreville, Gabon in July of 1977. The OAU Convention, del Prado notes, “was largely based on the draft produced by the International Commission of Inquiry set up by the Angolan government with the aim of having an objective evaluation of the Luanda judgment,” on the trial of thirteen Western mercenaries who had been sentenced to either long prison terms or execution for their actions against the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola in 1975. Unfortunately, the 1977 OAU Convention had its own crippling limitations.

As Nihal El Mquirmi writes for the Policy Center for the New South in, “Navigating in a Grey Zone: Regulating PMSCs,” by the time of the ‘77 OAU Convention, the Organization had been concerned about the issue of mercenaries for at least a decade, as the 1967 Assembly of Heads of State and Government of the OAU formally recognized that, “the existence of mercenaries constitutes a serious threat to the security of Member States,” and called on, “all States of the world to enact laws declaring the recruitment and training of mercenaries in their territories a punishable crime and deterring their citizens from enlisting as mercenaries.”

However, despite the prevalent belief among African governments that mercenaries had been, “partly responsible for ‘propping up’ illegitimate colonial regimes and threatening the independence aspirations of the African people,” for decades, and the concentrated efforts between 1967 and the adoption of the Convention in 1977 to restrict their usage, the definition of who precisely could be categorized as a mercenary in the ‘77 Convention imposed limitations on the document’s overall effectiveness. Specifically, Article 1 of the 1977 Convention defines as a mercenary, “anyone who, not a national of the state against which his actions are directed, is employed, enrols or links himself willingly to a person, group or organization whose aim is: a) To overthrow by force or arms or by any other means the government of that Member State of the OAU; b) To undermine the independence, territorial integrity or normal working of the institutions of the said State; c) To block by any means the activities of any liberation movement recognized by the OAU.”

Despite coming into force in 1985, El Mquirmi argues that the OAU Convention’s definition has been a limiting factor in that its definition only included individuals who were not a national of the state against which their actions are directed, which failed to “anticipate in its definition the recruitment of mercenaries by African state governments seeking to maintain sovereignty.” Moreover, El Mquirmi continues, not only does the OAU Convention lack a concrete enforcement mechanism, but, “because of the historical presence of mercenaries in Africa during and after the decolonization process, the OAU Convention only criminalizes the use of mercenaries when they hinder or oppose ‘by armed violence a process of self-determination, stability or the territorial integrity’ of an African state.” Further limiting the Convention’s applicability, as of 2013, only thirty-one out of fifty-four African Union states had actually ratified the document.

Additionally, the definitions of who could be labeled as a mercenary in the Geneva and OAU Conventions posed challenges in their application to the types of outfits operating worldwide during that period. However, another initiative took place at the United Nations to address the growing presence of mercenary groups. Nigeria, in a letter dated December 5, 1979, requested the inclusion of an agenda item on the “Drafting of an international convention against activities of mercenaries” for the thirty-fourth session of the UN General Assembly.

What’s more, while the Geneva and OAU Conventions’ definitions of who could be labeled as a mercenary made it difficult to apply to the type of outfits operating throughout the world at the time, there was another effort at the United Nations to address the ongoing rise of mercenary groups, with Nigeria sending a December 5, 1979 letter to the United Nations Secretary-General requesting that the thirty-fourth session of the UN General Assembly include an agenda item on, “Drafting of an international convention against activities of mercenaries.”

In December 1979, as a result of that request, the United Nations General Assembly adopted resolution 34/140 which recognized the threat that mercenarism posed to international peace and security, noting that, “like murder, piracy, and genocide, [mercenarism] is a universal crime against humanity,” and which called on all States to, “exercise the utmost vigilance against the menace posed by the activities of mercenaries and to ensure by both administrative and legislative measures that their territory…are not used for the planning…assembly, financing, training and transit of mercenaries designed to subvert or overthrow the Government of any Member State and to fight the national liberation movement of peoples which are struggling against colonial domination or alien occupation or racist regimes in the exercise of theri right of self-determination…” As part of that ‘79 resolution, the General Assembly called for the “drafting of an international convention to outlaw mercenarism in all its manifestations,” a process that would ultimately result in the 1989 International Convention against the Recruitment, Use, Financing and Training of Mercenaries (ICRUFTM), a document that, while welcomed, would unfortunately have its own crippling limitations.

The 1989 International Convention Against the Recruitment, Use, Financing, and Training of Mercenaries (ICRUFTM)

The 1989 International Convention Against the Recruitment, Use, Financing, and Training of Mercenaries (ICRUFTM), adopted in December of that year after nearly a decade of debate, contained a definition of mercenary that, while derived from both the 1977 Additional Protocols and the 1979 OAU Convention, “broadens the scope to include mercenaries operating in both international and non-international armed conflicts, but also in ‘any other situation.’” As Zarko Perovic wrote in a 2021 piece for Lawfare, the 1989 Convention, “has a five-factor test to determine who is a mercenary,” where, “a mercenary (a) is specifically recruited locally or abroad in order to fight in an armed conflict; (b) is motivated to take part in hostilities for private gain and is promised material compensation substantially in excess of that promised or paid to combatants of similar rank and functions in the armed forces of that party; (c) is neither a national of a party to the conflict nor a resident of territory controlled by a party to the conflict; (d) is not a member of the armed forces of a party to the conflict; and (e) has not been sent by a state that is not a party to the conflict on official duty as a member of its armed forces,” where an individual who fulfills those criteria and who, “participates directly in hostilities or in a concerted act of violence,” being in violation of the Convention.

However, the ‘89 Convention’s definition, as Nihal El Mquirmi points out, “excludes PMSCs that have operated in Iraq or in Afghanistan, contracted to protect the government and the territorial integrity of the state in which they operate.” Furthermore, the 1989 ICRUFTM lacks a monitoring body, which leaves enforcement up to individual member states, limiting the text’s practical applicability. Compounding ICRUFTM’s definitional issues, as José L. Gómez del Prado writes in, “A United Nations Instrument to Regulate and Monitor Private Military and Security Contractors,” the specific elements of the definition, when taken individually, pose problems on their own, specifically noting that:

“for example: the person has had to be recruited to combat, i.e. to take part in direct hostilities. This has to be specified in the contract, which usually is not. In addition, the person may or not be taking part in direct participation in hostilities, which is not always the case. The question of proving that the person is only motivated by the desire of gain is extremely hard to prove. As to the question that in order to be a mercenary the person must not be a national or a resident of a party to the conflict excludes a large number of persons. For instance, under this criteria all the citizens of countries participating in the Iraq war (Americans, British, Dutch, etc.) would not be catalogued as mercenaries.”

What’s more, del Prado notes, “one has to bear in mind that the five elements of the definition are cumulative, and all of them must be fulfilled: not only one or a few.” In addition, he argues that, “other problems which had not been envisaged at the time have appeared now with the contracting out of military and security functions to the private sector. For instance, the definition is ambiguous or does not foresee the activities of PSMCs in armed conflicts. It does not make the distinction between active and passive participation in combat. It leaves out the training of militaries, the operational assistance to the armed forces and the strategic planning.”

In addition, as the Center for Civilians in Conflict alleged in a 2022 Issue Brief, “the criteria required to meet the…[ICRUFTM] definition of ‘mercenary’…[is] notoriously difficult to satisfy, rendering a ban on the use of mercenaries close to meaningless in practice.” On top of that, as Michael Scheimer points out in a 2009 American University International Law Review article, “only those countries that sign [ICRUFTM] are bound by it,” despite the fact that ICRUFTM, “has garnered even less support than Article 47: it has taken decades to come into effect, and far fewer states have signed [ICRUFTM] than ratified Article 47.” Scheimer additionally emphasizes that, “a [private military company [could find it easier to escape the language on compensation in [ICRUFTM] than the similar clause in Article 47, because the [ICRUFTM] language allows for official duty on behalf of a state, not just as a member of the armed forces,” so a state agency can contract with a private military or security firm to perform official state duties to avoid the Convention’s definition.

Adding to these difficulties, as Amol Mehra writes in a January 2010 paper, “Bridging Accountability Gaps: The Proliferation of Private Military and Security Companies and Ensuring Accountability for Human Rights Violations,” the problems with ICRUFTM and the prior international definitions of mercenary are numerous. According to Mehra, “although [ICRUFTM] makes it a crime to be a mercenary, the enforcement of this crime depends on implementing legislation by the relevant state party.“ Additionally, Mehra notes that the rights mentioned in the 1989 Convention encompass, “self-determination” despite the fact that, “business activity impacts multiple internationally recognized rights, including the right to life, liberty and security of the person.”

The result of these, “tremendous loopholes in coverage over PMSC actors under the Convention Against Mercenaries,” is that, “the Geneva Convention and other such international treaties, showcases the urgent need for an international consensus on accountability for the corporate entity and not just the contractors,” involved in mercenary activities. However, José L. Gómez del Prado has written, “the aim of such a binding legal instrument is not the outright banning of PMSCs, but rather to establish minimum international standards for States parties to regulate the activities of PMSCs and their personnel,” and that, “in addition, taking into account the extensive outsourcing of military and security functions and the growing role of PMSCs in armed conflicts, post-conflict and low intensity armed conflict situations it is also recommended to prohibit the outsourcing of inherently State functions to PMSCs in accordance with the principal of the State monopoly on the legitimate use of force.”

Towards a More Industry-Led Approach

If the 1977 Additional Protocols, the 1979 OAU Convention, and the 1989 ICRUFTM Conventions failed to deliver on the promise of actually restricting the use of the PMSC industry, it was largely due to the resistance these various conventions have received from Western countries. As Amol Mehra highlighted, “in 1999, the U.N. Development Program concluded, ‘multinational corporations are already a dominant part of the global economy—yet many of their actions go unrecorded and unaccounted. They must, however, go far beyond reporting to just their shareholders. They need to be ‘brought within the frame of global governance, not just the patchwork of national laws, rules and regulations.”

However, despite this half-century old conclusion, as del Prado contends, “the position of Western countries in the U.N. has been a rejection of regulation and oversight mechanisms,” as a significant portion of the booming industry is headquartered in Western nations, providing those nations with tax receipts and politicians through extensive domestic and international lobbying. Instead, what Western nations have instead favored has largely been a more neoliberal regulatory approach to the industry.

Starting in 2005, the government of Switzerland initiated talks with the International Committee of the Red Cross in what would become known as the “Swiss Initiative”, “regarding the need for intergovernmental dialogue on the application of [international humanitarian law] and human rights law to PMSCs.” This process involved a two-pronged approach, with one aspect focusing on industry commitment to establishing an international “code of conduct” for firms, while the other aspect examined efforts to clarify existing international law governing these firms. The resultant document, issued by the Swiss and ICRC in September of 2008 on, “Pertinent International Legal Obligations and Good Practices for Related States to Operations of Private Military and Security Companies during Armed Conflict,” would become known to the rest of the world more commonly as the Montreux Document.

As James Cockayne points out, “over the course of two meetings (16–17 January 2006, in Zurich, and 13–14 November 2006, in Montreux), 16 states, the European Commission, the ICRC, the British Association of Private Security Companies (BAPSC), the International Peace Operations Association (IPOA), and civil society and academic experts began to identify elements of practice that might be recommended to states and industry.” While the participants acknowledged that there were existing international obligations for firms and a patchwork of international and State laws governing PMSC conduct, “some states sounded a note of caution about the proposed ‘standards’ or ‘elements of recommended regulatory practices’ section, arguing that the very different approaches to regulation at the national level…made comparison between such approaches problematic.” Consequently, these states, “signaled that they would not agree to a document that established binding standards or singled some practice out as the ‘best’—or even as ‘recommended’. Others went further, claiming that it might, in fact, prove difficult to identify any relevant regulatory practice—so calls for elaboration of best practice were perhaps premature. As a result, participants began talking of the second section of the proposed output as an elaboration of ‘good practice’, even as civil society actors cautioned that this risked watering down the authority of any output from the Initiative.”

This process ultimately led to a diluted end-product, as could be predicted. While widespread State buy-in is certainly desirable, the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA) and the ICRC adopted a more, “conservative approach to the statement of state obligations with the extensive involvement of governmental and non-governmental experts in the development of ‘good practices’.” Although the Swiss FDFA and ICRC were careful to emphasize that the Initiative was not intended to legitimize the industry in any way, José L. Gómez del Prado argues that instead, the resulting document, “stamp[s] its seal of legitimacy on PMSCs,” as the Montreux Document in reality, “recognises de facto this new industry and the military and security services it provides. It legitmises the services the industry provides, which still remain unregulated and unmonitored.”

The Montreux Document is organized into distinct sets of ‘good practices’ tailored for different entities involved in private military and security companies (PMSCs). These include contracting states, which directly engage PMSCs and subcontractors, territorial states where PMSCs operate, and home states where PMSCs are registered, incorporated, or have their principal place of management. However, the document’s impact is inherently limited due to its non-binding nature. The Montreux Document explicitly states in its Preface that, “this document is not a legally binding instrument,” watering down its potential efficacy.

The development of the Montreux Document coincided with the creation of the International Code of Conduct for Private Security Service Providers (ICoC) and the subsequent establishment of the International Code of Conduct Association (ICoCA). The ICoCA is a multi-stakeholder initiative composed of industry firms, select governments, and a few human rights advocacy non-governmental organizations, tasked with overseeing the implementation of the code. This initiative aimed to establish voluntary industry standards for behavior and involved industry associations such as the International Peace Operations Association (IPOA), the British Association of Private Security Companies (BAPSC), as well as individual business leaders, along with the Swiss, UK, and U.S. governments.

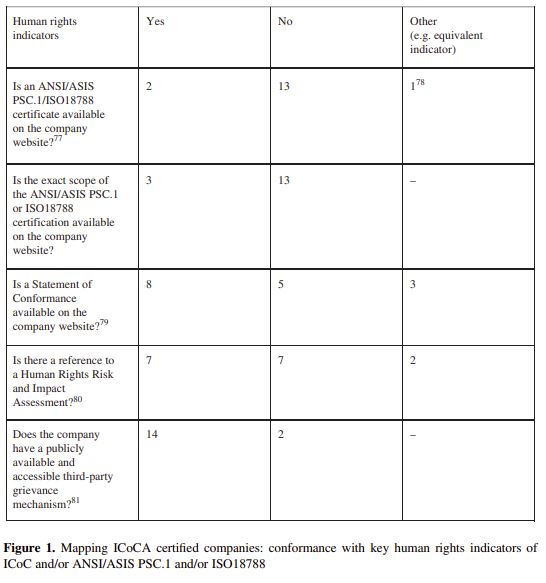

Despite this development, as Christopher Kinsey and Col. Christopher Mayer wrote in a 2022 piece for King’s College London’s Defence-in-Depth early last year, “participation in the ICoC has been less successful than the initial enthusiasm for the Code might have suggested,” as, “at its height, only 115 Private Security Companies were members, and as of December 2021, membership stood at just 66 PSCs.” Moreover, Kinsey and Mayer note that, “government participation has also failed to meet expectations,” as,” only seven of the 58 governments that participate in the Montreux Document and its Forum are members of the ICoCA,” and, “of those seven members, none are developing nations which are typically most at risk from non-state armed groups.”

The central idea underpinning the creation of the Code of Conduct—that the industry, driven by the desire for continued Western governmental contracts, would voluntarily regulate itself to avoid human-rights related incidents that could jeopardize future contracts—is ultimately a flawed one, however. As the events of the 2008 financial crisis should have clearly demonstrated, the neoliberal, laissez-faire attitude towards the regulation of important industries is a clear recipe for disaster. Figures such as the former U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan, who said just a year before the 2008 financial crisis that, “thanks to globaliation, policy decisions in the US have been largely replaced by global market forces,” exemplified this neoliberal belief in the overwhelming power of markets to deliver benefits for all as long as they are left to their own devices.

However, champions of industry self-regulation such as Greenspan recognized too late the error of this way of thinking, conceding in testimony before the House Government Oversight and Reform Committee in the immediate aftermath of the financial collapse that, “those of us who have looked to the self-interest of lending institutions to protect shareholders equity, myself especially, are in a state of shocked disbelief. ” This acknowledgment by Greenspan illustrates the recognition of the failures within his industry to self-regulate, which ultimately resulted in an explosion of risky behavior that led to the subprime mortgage meltdown.

Even when confronted with the full extent of self-regulations’ failures, a neoliberal such as Greenspan could not resist seeing this failure as an isolated incident, saying before the same Committee that, “I suspect that we are going to find that this is a very chastened market and that many of the problems that we’ve observed during the euphoria stage of the [industry] expansion will not be back if—at any time if ever.” But despite the former Fed Chair’s prognostication, the industry continued acting recklessly, whether it was through the LIBOR manipulation scandal or the foreign exchange manipulation scandal, demonstrating the dangers that come with industry self-regulation.

Benjamin P. Edwards, from the UNLV William S. Boyd School of Law, explored the premise of self-regulation within the financial services industry in 2017. He noted that the main premise behind self-regulation is that, “the industry has a strong incentive to police itself in order to maintain its quality.” However, Edwards cautioned that “profit-seeking industry self-regulators will likely define ‘misbehavior’ as actions that impose costs or reduce the profits of the industry as a whole—not necessarily as activities that reduce investor welfare or generate costs elsewhere.” He notes, for example, that self-regulating manufacturers may not limit pollution because their distant customers may not bear the local environmental costs resulting from their operations. This same issue is evident within the PMSC industry, as industry-led initiatives like the Montreux Document do strive to uphold a certain standard of overall quality. However, the profit-seeking pressures faced by industry actors tend to prioritize punishing behavior that impacts the industry’s bottom line, rather than embracing rules and regulations that restrict firms’ ability to contract with clients who may not prioritize human rights and international humanitarian law as much as Western audiences do.

Just as banks’ own, “customers may even prefer pollution-spewing factories because they pay less for goods and bear no liability for the environmental cleanup,” many of the PMSC industry’s biggest growth clients, from the United Arab Emirates to Russia or China may not have the same human rights concerns regarding the industry as do many experts in the West. Christopher Spearin highlighted this issue in his article for the National Defense University’s PRISM in June 2020 when he noted that, “due to the aggressive bent of some Chinese non-state actors, the resource-centric elements of China’s relationship with Africa and the BRI, and the fact that China is not a signatory to the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights, one could envision a more provocative and assertive China following a similar path,” to that of Russia, which has used its PMSCs such as Wagner to further the state’s extractive interests in Africa despite frequent human rights violations by these firms in securing thsoe extractive rights.

In the end, although industry best practices serve as an interim measure towards establishing binding international regulations, they cannot serve as the sole guiding principle for the industry. The Montreux Document’s approximately seventy recommendations, lacking any meaningful enforcement mechanisms, remain mere suggestions without any legal authority. While the U.S. Department of Defense has established requirements for adherence to industry standards like ANSI/ASIS PSC.1-2012 or ISO 18788, which “implement the recommended good practices of the Montreux Document,”incorporate the recommended good practices of the Montreux Document, not all countries have implemented similar requirements. Furthermore, it is worth noting that the U.S. Department of Defense does not, “not require membership, certification and oversight,” by the International Code of Conduct for Private Security Service Providers’ Association (ICoCA).

Furthermore, according to Kinsey and Mayer’s analysis in their piece for Defence-in-Depth, it is alarming to note that, “there are 27 ongoing armed conflicts in the world today, at least 19 of which include activity by armed contractors,” highlighting the worrisome lack of tangible outcomes from the Montreux and ICoC processes. They also point out the case of Yemen, where the, “Ministry of Interior and Trade recognises 35 domestic companies that meet the ICoC definition of a PSC, as well as the activity of foreign PMSCs,” despite neither the country nor its domestic firms being members of the International Code of Conduct Association (ICoCA). This raises concerns as Kinsey and Mayer argue that recent amendments to the ICoC, broadening the scope and definition of security services, may, “have the effect of opening the political and normative gates to legitimizing combat provider organizations such as Russia’s quasi-mercenary group Wagner and the South African PMC Specialised Tasks, Training, Equipment and Protection (STTEP).” Kinsey and Mayer caution that, “outsourcing this type of activity without sufficient state oversight and control also carries considerable risks to human rights.”

Finally, as Raymond Saner submits: “The PMSC industry has presented an astonishing ability to protect itself from regulatory sanctions by showing evidence of entrepreneurial efforts, such as the creation of the new ISO standard described above. This suggests that the industry has the ability to fend off criticism and create a new quasi-regulatory space that it can use to counter attempts to tighten regulation through new inter-governmental initiatives such as the Montreux Document and the related ICoC described below. Furthermore, in Nihal El Mquirimi’s Navigating in a Grey Zone, the author points to a quote from Raymond Saner who argues that:

“The PMSC industry has presented an astonishing ability to protect itself from regulatory sanctions by showing evidence of entrepreneurial efforts, such as the creation of the new ISO standard described above. This suggests that the industry has the ability to fend off criticism and create a new quasi-regulatory space that it can use to counter attempts to tighten regulation through new inter-governmental initiatives such as the Montreux Document and the related ICoC…”

But despite the industry’s best efforts, there have been attempts to create stronger restrictions on PMSC firms’ behavior.

The UN Working Group on the Use of Mercenaries and Work Towards a Binding International Convention

In 2005, the UN’s Commission on Human Rights and Human Rights Council recommended the formation of a Working Group on the Use of Mercenaries (WGUM). The WGUM consists of five independent experts entrusted with several objectives: presenting proposals on new standards and guidelines to protect the right of peoples to self-determination when facing threats posed by mercenaries; soliciting contributions from governments, intergovernmental, and nongovernmental organizations on matters related to its mandate; monitoring mercenary-related activities worldwide; identifying emerging issues and trends concerning mercenaries and their activities, particularly their impact on human rights; and conducting a study on the effects of private companies offering military assistance, consultancy, and security services on the international market, specifically on the enjoyment of human rights, notably the right of peoples to self-determination. What’s more, as Saeed Mokbil, Chairperson-Rapporteur for the WGUM argued in 2018, “mercenary-related activities undermine [Sustainable Development Goal] 16.2 to end abuse, exploitation, trafficking, and all forms of violence against and torture of children.”

Since the WGUM’s formation in 2005, it has studied reports of mercenary activities and, through its thematic reports, provided key analysis of ongoing developments in the industry. Moreover, the UN’s own report, “Mercenarism and Private Military and Security Companies,” from 2018 notes that, “the Working Group has maintained the position that the most effective way to regulate private military and security companies is through an international legally binding instrument,” even if it has also recognized the importance of such self-regulatory regimes as the Montreux Document.

Unfortunately, however, the Working Group received little support from Western governments in working towards that goal. Although the Working Group had identified over a decade ago, “that there is a regulatory legal vacuum covering the activities of PMSCs and a lack of common standards for the registration, and licensing of these companies as well as for the vetting and training of their staff and the safekeeping of weapons,” there has been insufficient Western support for the Working Group’s attempts to create a Draft Convention due to a combination of Western states fearing that the proposed Convention would place too stringent limits on the industry and a belief that existing industry codes of conduct suffice as far as industry guardrails go.

Still, the proposed Draft Convention—which has been in the works for over five years at the UN Open-Ended Intergovernmental Working Group on PMSCs (IGWG) where primary responsibility for developing the draft shifted after that body’s creation in September 2017—offers numerous advantages and could ideally serve as the foundation for a binding international regime governing the PMSC industry going forward. However, despite the proposed convention having, “attracted support from a range of developing countries, notably Cuba and South Africa,” the proposed drafts have, “largely failed to receive support from Western countries, which host most of the PMSC industry.”

According to the most recent progress report from the IGWG, the proposed draft convention is still undergoing revisions by IGWG members. However, representatives from the European Union, Switzerland, Russia, Mexico, Japan, and the UK have all expressed a strong belief that the Montreux Document and ICoC are sufficient frameworks for ensuring industry compliance with international human rights law. They have cast doubt on the necessity of a UN-led binding international standard for regulating industry behavior. This widespread skepticism towards a binding international convention undermines the overall process and diminishes the likelihood that the IGWG, in its current form, will produce a document that meets the requirements of Western states, which hold a financial stake in the continued prosperity of PMSC firms.

While this skepticism is understandable to some extent, it is imperative to overcome it in order for the world to assert control over the actions of private military and security companies. According to former WGUM member José L. Gómez del Prado, there are several reasons why a binding international instrument to regulate PMSC conduct is necessary, starting with the fact that there currently exists a, “regulatory legal vacuum covering the activities of PMSCs and a lack of common standards for the registration, and licensing of these companies as well as for the vetting and training of their staff and the safekeeping of weapons.” Furthermore,PMSC services cannot be treated as, “ordinary commercial commodities that can be controlled through self-regulation initiatives,” as their functions involve a range of military and security services normally restricted to the state. Finally, del Prado argues that existing international definitions of who is a mercenary are all too limiting to encompass all of those working in the PMSC industry. Therefore, the international community must develop a new, binding, and all-encompassing definition of a mercenary in order to effectively regulate firms’ behavior.

The United States’ (Failed) Attempts to Regulate the Industry

As Michael Scheimer argues in a 2009 paper for the American University International Law Review, “in the absence of solid international support for the Article 47 and U.N. Convention definitions to apply to [PMSCs], the only recourse for [PMSC] regulation is domestic regimes…However, even U.S. domestic law has been revealed to be insufficient…”

While the United States does have some of its own guidelines on the use of PMSC firms, Transparency International’s Michael Picard and Colby Goodman argue that the U.S. still has, “key gaps in regulation and transparency of US PMSC’s contracts with foreign governments.” The authors suggest that while the U.S. State Department’s Director of Defense Trade Controls (DDTC), “requires US PMSCs to obtain their approval (via a license) to provide some types of PMSC-related services…these regulations, however, have wide gaps in oversight when US PMSCs or US persons working with foreign PMSCs seek to provide direct combat support to foreign entities abroad.” Moreover, the authors state that, “there are some critical gaps in US oversight of PMSCs who contract with the US Government,” in that differing US agencies maintain different controls as well as varying degrees of oversight over PMSC firms.

Finally, Picard and Goodman contend that U.S. government efforts to address the challenge of regulating U.S.-based PMSCs, “will not be fully effective unless [the U.S.] pushes foreign countries to adopt stronger national laws on their PMSCs,” as many U.S.-based firms hire employees from all around the globe, and many of the countries where these personnel come from, “have not signed or implemented key non-binding international agreements, such as the Montreux Document and the International Code of Conduct,” leaving huge gaps in international efforts to regulate the industry.

Additionally, as José L. Gómez del Prado contends, the report of the Senate Armed Services Committee, “Inquiry into the Role and Oversight of Private Security Contractors in Afghanistan,” approved in October 2010, reveals the threat that security contractors operating without adequate government supervision had posed to the U.S. mission in Afghanistan. Furthermore, P.W. Singer highlights the alarming conduct of Blackwater personnel during the March 2004 Fallujah incident when, “without any coordination with the local Marine unit, a Blackwater convoy drove through Fallujah, was ambushed, and the 4 contractors killed,” an incident so strongly redolent of the 1990s Black Hawk Down incident in Mogadishu that prompted the Bush administration to launch the First Battle of Fallujah.

More concerningly, in a subsequent wrongful death lawsuit filed against the PMSC by the mothers of the four dead contractors, it was alleged that the firm, “had rushed together a team of 4 men who had never trained together and sent them out without armored vehicles and even good directions.” The lawsuit claimed that, “Blackwater had just won the contract and reportedly wanted to impress the client, a Kuwaiti holding company, that it could get the job done,” thus illustrating the inherent dangers that arise when combining the concept of shareholder primacy with the private use of military force in conflict zones.

Further complicating the situation, despite industry claims that the use of contractors in America’s recent conflicts aimed to reduce costs for taxpayers, the Commission on Wartime Contracting in Iraq and Afghanistan’s report, “At What Risk? Correcting Over-Reliance on Contractors in Contingency Operations,” revealed a troubling finding. Between 2001 and 2001, over $177 billion was allocated to contracts and grants supporting U.S. operations in the two countries, not to mention an additional approximately $208 billion projected for the period between 2009 and 2018. Shockingly, the report concluded that, “widespread and repeated instances of waste, fraud, and abuse suggest that tens of billions of taxpayers’ dollars have failed to reach their intended use in Iraq and Afghanistan.”

“Furthermore, in a May 2011 Congressional Research Service report by Moshe Schwartz, it is highlighted that Congress had various options available to mitigate the potential negative impact of PMSCs on U.S. operations in Iraq, Afghanistan, and other regions. These options included the clearer definition of the roles PMSC personnel may assume during military operations, such as: : a) prohibitions on security contractors being deployed in combat zones; b) restrictions on their PMSC use to just static site security; c) restricting armed contractors to static security work only, with the exception of local nationals; and d) requiring a majority of personnel used for convoy security to be uninformed personnel in order to retain DOD command and control of such potentially dangerous operations.

Largely in response to the Commission on Wartime Contracting report, Illinois Representative Jan Schakowsky and Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders announced plans to reintroduce their Stop Outsourcing Security Act, which aimed to prohibit the use of private contractors for military, security, law enforcement, intelligence, and armed rescue functions due to instances of fraud, waste, abuse—as well as the events of Nisour Square and other human rights violations committed by PMSC personnel. The bill would have required that the U.S. military train partner troops and militaries, as well as to provide security for U.S. diplomats around the world. Furthermore, the legislation would have subjected contracts exceeding $5 million to Congressional oversight, as well as the total number of contractors employed, and the total costs of the contracts. Moreover, it would require firms accepting large U.S. government contracts to disclose a description of any disciplinary actions taken against contractor personnel.

However, despite gaining thirty Democratic cosponsors, the bill languished in the House and has not been resurrected since. Although it was not the final attempt to regulate the Private Military and Security Contractor (PMSC) industry in the United States, the Stop Outsourcing Security Act was the most ambitious legislation proposed to restrict the use of such firms in U.S. operations. The failure to advance the legislation represented a missed opportunity for the U.S. to take meaningful action in limiting PMSC use in future operations. Nevertheless, it does not eliminate the possibility of doing so in the future. In fact, if the United States genuinely desires to witness an improvement in industry behavior, it must make the decision to lead on the issue by enacting comprehensive national legislation that governs the use of PMSCs.

While the U.S. does retain some ability to punish misbehavior by U.S. PMSC personnel through instruments such as the Defense Base Act, the Military Extraterritorial Jurisdiction Act (MEJA) and the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ)—which was amended in the 2007 NDAA to place contractors accompanying the military in the field under the Uniform Code not just in times of war but in contingency operations—the laws do not encompass all of the actions taken by such firms in conflict zones, resulting in an inability to hold offenders accountable for their actions.

As Reema Shah highlights in a 2014 article for the Yale Law Journal, although MEJA was expanded in 2004 to enable the prosecution of contractors supporting DOD missions abroad for crimes that would warrant over one year of imprisonment if committed within the U.S., “MEJA and the UCMJ can only be used to prosecute individuals.” Additionally, as was articulated in an August 2008 Congressional Research Service report by Jennifer K. Elsea, Moshe Schwartz, and Kennon H. Nakamura, “depending on how broadly DOD’s mission is construed, MEJA does not appear to cover civilian and contract employees of agencies engaged in their own operations overseas. It also does not cover nationals of or persons ordinarily residing in the host nation.”

Moreover, as the 2008 CRS report accurately points out, “while [MEJA] appears to cover other foreign nationals working under covered contracts, it does not appear to extend federal jurisdiction over crimes not expressly defined as covering conduct occurring within the [special maritime and territorial jurisdiction]…For example, it might not be available as a jurisdictional basis to prosecute non-U.S. national contractors for war crimes under 18 U.S.C. § 2441.” This limitation exists despite the fact that, “the workforce of the US PMSC industry is typically ex-military and heavily internationalized,” as while most firms are owned and operated by military vets, “such companies will typically assign Western managers to oversee [third-country nationals] or local nationals, who are cheaper to staff the contract,” resulting in a much lower level of contractor oversight than if the operations were being carried out by U.S. nationals.

As a result of this, by 2008, “very few successful prosecutions involving DOD contractors in Iraq under MEJA [had] been reported,” with the few successful examples given being a contractor who pled guilty to the possession of child pornography in 2007 and the prosecution of another contractor for sexually assaulting a female soldier at Tallil Air Force Base in 2004.

Furthermore, while the 2007 NDAA expanded the UCMJ to cover civilians during contingency operations, it too has been seldom used to prosecute malfeasance. As Raymond Lu, Britta Redwood, and Jacqueline Van De Velde note in their article, “Inherently Governmental Functions and the Role of Private Military Contractors,” in the period between 2006 and when the authors published in 2017, “only one individual has been prosecuted under this revised statute: an interpreter who stabbed a coworker,” as, “prosecutions have been hampered by ambiguities about how directly connected to the military PMSCs must be in order to qualify as ‘serving or accompanying an armed force’ and whether ‘in the field’ extends to non-traditional battlefields.” Moreover, the authors acknowledge that, “trying civilian contractors in military courts remains highly controversial, as it threatens to erode protections normally afforded to criminal defendants under the U.S. constitution.”

In light of these challenges, efforts were made to strengthen existing U.S. legislation, including the MEJA and UCMJ, to address gaps in prosecuting criminal violations committed by U.S. citizen contractors employed by non-Department of Defense agencies. As a 2012 CRS report from Charles Doyle notes, a proposed Civilian Extraterritorial Jurisdiction Act (CEJA – H.R. 2136) would have established a new 18 U.S.C. § 3272, “outlawing conduct outside the United States by anyone ‘employed by or accompanying any department or agency of the United States other than the Department of Defense,’ when the conduct would be criminal if committed within the United States or within its special maritime and territorial jurisdiction.”

The proposed legislation would have also, “reach[ed] the crimes of a wider range of non-Defense Department employees, contractors, and attendants than MEJA,” which, “reaches the crimes of a few.” However, as Lu, Redwood, and Van De Velde acknowledge, the idea of, “trying civilian contractors in military courts remains highly controversial, as it threatens to erode protections normally afforded to criminal defendants under the U.S. constitution.” As a result, the 2014 legislation ultimately died in Congress, and has yet to be taken up again..

As a further result of these failures, as Cedric Ryngaert notes in, “Litigating Abuses Committed by Private Military Companies,” while opportunities to pursue PMSCs through criminal and civil litigation do exist, “obstacles—whether legal, procedural, political, practical, or otherwise—to successful litigation seem to be abound.” The most obvious issues in the field of criminal law, as Ryngaert highlights, are that, “some violations do not amount to crimes over which the hiring state can exercise extraterritorial jurisdiction,” and that, “concerns over the sovereignty of foreign nations may arise, criminal trials of civilian contractors under military law may prove illegal, corporations may not be held criminally liable, and state prosecutors may not be particularly keen on initiating prosecution against [those PMSCs that are] contributing to the war effort.”

Moreover, despite, as Ryngaert argues, “in view of those obstacles, it is not surprising that the gaze of the accountability advocates has turned to tort law, it is not just the application of criminal statutes to PMSC personnel that has proven difficult, as Lu, Redwood, and Van De Velde note that, “private civil suits against U.S. PMSCs face similarly daunting challenges,” as while, “plaintiffs have attempted to use the Alien Tort Statute (ATS) and common law torts to hold U.S.-based PMSCs accountable…PMSC defendants have successfully raised jurisdictional challenges and asserted broadly defined immunities to shield themselves from liability.” They specifically emphasize that, “the D.C. Circuit—the country’s most influential appeals court—has dismissed ATS suits brought by families of victims who were tortured and murdered at Abu Ghraib, holding that the conduct of PMSCs did not qualify as ‘state action’ and thus did not violate settled norms of international law that primarily regulate governments.”

What’s more, Lu, Redwood, and Van De Velde maintain, “PMSC defendants have also defeated civil suits by invoking immunities rooted in their contractual relationships with the U.S. government,” with the U.S. federal district court in Al Shimari v. CACI Premier Technology, Inc. dismissing, “claims brought by Abu Ghraib victims against interrogators employed by CACI , reasoning that the U.S. military chain of command exercised ‘plenary’ and ‘direct’ control over interrogators at the prison and that a decision on the merits of the claim ‘would require the judiciary to question actual, sensitive judgements made by the military,’” resulting in the ultimate dismissal of twenty claims alleging torture, war crimes, and cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment (CDIT) by CACI and its personnel against prisoners at the facility..

Also limiting plaintiff’s ability to go after PMSCs engaged in malfeasance is the fact that, “some PMSC defendants have escaped liability by arguing that any abuses committed in Iraq and Afghanistan were part and parcel of the U.S. military’s ‘combatant activities’ during a time of war and thus protected by sovereign immunity.” Indeed, in Saleh v. Titan Corp., Lu, Redwood, and Van De Velde highlight that, “the D.C. Circuit extended this reasoning to dismiss a lawsuit brought by victims of torture at Abu Ghraib against two PMSCs, holding that the companies had acted as extension of the military in conducting interrogations and were consequently entitled to immunity,” even after the court had acknowledged that CACI em ployees had, “operated under a dual command structure in which company site managers had independent authority to halt abusive interrogations.”

However, going beyond existing legal barriers to prosecuting PMSCs under U.S. law is the simple fact that, “more broadly, both criminal and civil cases against PMSCs have suffered from evidentiary obstacles,” as the simple act of obtaining physical evidence and witness testimony about events that have taken place in an active conflict zone is something that is much easier said than done. As Lu, Redwood, and Van De Velde emphasize, “procuring witnesses for a trial may be particularly burdensome, as prosecutors or plaintiffs must persuade them to testify, provide for their security and (potentially) the safety of their family, and arrange travel. For example, U.S. prosecutors were able to convict a CIA contractor for assaulting an Afghan detainee in 2007, only because a key witness was willing and able to travel to the United States and other witnesses were U.S. citizens who could be subpoenaed.”

When coupled with the lack of enforcement systems in the Montreux Document and the International Code of Conduct for Private Security Providers, it becomes evident that there is a troubling absence of actionable legislation governing PMSC activities. Consequently, it is crucial for the U.S. government to explore potential avenues and embrace its role as a global leader to address this issue. One possible approach is to develop comprehensive regulations specifically tailored to the United States, while also encouraging the European Union—a body aspiring to be a leader in global rule-setting—to adopt similar measures. By taking these steps, both the U.S. and Europe can contribute to establishing robust global rules, standards, and norms that guide not only the private military and security industry, but technology, trade, and economic development, as well.

Towards a Binding International Convention Governing the PMSC Industry

As far back as 2011, Moshe Schwartz highlighted, “the perception that DOD and other government agencies are deploying PSCs who abuse and mistreat people can fan anti-American sentiment and strengthen insurgents, even when no abuses are taking place.” In his piece, Schwartz points to a paper from Col. Bobby A. Towery who, writing back in 2006 for the U.S. Army War College said that, “after [the U.S. departure from the country], the potential exists for us to leave Iraq with paramilitary organizations that are well organized, financed, trained, and equipped.” Towery continued that these organizations were, “primarily motivated by profit and only answer to an Iraqi government official with limited to no control over their actions.” As such, Towery concludes that, “these factors potentially make private security contractors a destabilizing influence in the future of Iraq.”

Moreover, as Sean McFate notes in his own 2020 paper for the WGUM, “Mercenaries and Privatized Warfare: Current Trends and Developments,” while, “thousands of mercenaries got their start in Iraq or Afghanistan,” when those wars were wound down, those same mercenaries, “set out looking for new conflict markets (AKA war zones) around the world, enlarging the wars there.” Indeed, the market expanded so much and so fast that some American ex-soldiers even ended up running a targeted assassination program in Yemen for the UAE as the Obama administration continued its support for the Saudi proxy war in that country despite the bloodshed.

Compounding the continued growth of the industry outside of the U.S. is the fact that, as McFate notes, “the demand for overt or ‘legitimate’ private security firms has severely dipped since the U.S. left Iraq and has reduced its footprint in Afghanistan. The situation is driving the entire industry underground, as they seek new opportunities from clients not interested in transparency.”

Further complicating the private military and security landscape is the fact that, as Berenike Prem concludes in a 2021 paper for Contemporary Security Policy, multi-stakeholder initiatives such as the ICoC and the Montreux Document, “are heavily biased towards those actors that accept PMSCs as normal and legitimate security actors; impose constraints on the behavior of their NGO participants; marginalize dissenting voices; and legitimize the status quo of security privatization.” Prem argues that efforts such as Montreux and the ICoC were all simply efforts to avoid the limits of a proposed WGUM Draft Convention, which, “would have amounted to nothing less than a partial ban on PMSC activities.” According to Prem’s analysis, “the efforts of the Working Group…were therefore met with resistance from the major home and contracting states of PMSCs,” which were, “anxious to retain their flexibility in using,” such firms in future operations.

As such, Prem contends, countries like the U.S., UK, and Canada—which were hostile to the very notion of binding international legislation—instead turned to the Swiss Initiative and industry-led efforts like the ICoC, as such multi-stakeholder initiatives are largely performative as, “certification and monitoring produce already what they seek to achieve: the creation of the ‘compliant’ and ‘socially responsible PMSC—irrespective of how these companies perform on the ground.” Furthermore, while the ICoC Association was formed with the goal of giving the ICoC some real teeth, Prem suggests that, “as much as the ICoC implied a wholly new level of scrutiny and constraints to which the industry was subjected, it allowed PMSCs to retain the ownership over their fate.”

Further diluting the efficacy of industry self-regulation was the fact that the NGO community was largely sidelined as a, “growing pro-privatization consensus,” which has been, “achieved by marginalizing actors which have taken strong and non-pragmatic positions,” on industry regulation. Most damningly, Prem points to the statement of one PMSC industry multi-stakeholder participant who, illustrating contempt for the very idea that the entire industry might need some curtailing, said that:

“There are organizations [that] accept that there is a PMSC industry and there-fore seek […] to help that industry perform in a proper fashion. And there are some NGOs who would still almost deny the fact that there is an industry and would like to see it all closed down. That sort of position I don’t think is strictly helpful because, to my mind, it’s not going to happen. […] So whether people like it or not, to be frank, […] the industry is there to stay and the important thing is making sure that those companies that deliver services to a high standard are recognized doing so […]”

As Prem submits, in many—if not most—discussions regarding industry regulation, “expert status accrues to actors which take ‘realistic,’ ‘pragmatic,’ and ‘constructive’ positions as opposed to those exhibiting ‘unrealistic,’ ‘dogmatic,’ and ‘counterproductive views,’” with the important caveat that what determines “pragmatic” or “counterproductive” is often simply defined as those who are willing to accept the status quo, keeping those who want more robust regulation on the outside of these negotiations. More troublingly, these multi-stakeholder initiatives often end up co-opting more critical voices who, endeavoring to be seen as “reasonable” and “productive”, often end up blunting their criticisms so as not to be seen as “unreasonable” outsiders who are likely to become marginalized in future talks.

As Andrea Schneiker and Jutta Joachim suggest in, “Revisiting Global Governance in Multistakeholder Initiatives: Club Governance Based on Ideational Pre Alignments,” in such multi-stakeholder initiatives, “the individual entrepreneurs who represent the collective actors…can be viewed as a club that decides which other civil society actors are relevant and will be allowed to join their circle and participate in the multistakeholder initiatives.” Thus, such multi-stakeholder initiatives, “while often viewed as opportunities for more societal participation,” in actuality, “in fact silence already marginalised positions and groups even further, and in doing so reproduce existing hierarchies and power relations on a global scale.”

In a similar vein, Berenike Prem contends that although NGOs like Amnesty International or Human Rights First were initially skeptical of the industry, they have since shifted their stance, acknowledging the industry’s potential contribution to ensuring respect for human rights and praising its commitment to regulation.