September 10, 2021

Back in July, Chatham House published a fascinating research paper by John Lough, “Ukraine’s system of crony capitalism: The challenge of dismantling ‘systema’”, which examines the extent to which oligarchs exert control over the Ukrainian economic system, as well as efforts by the government of Volodymyr Zelenskyy to combat the endemic corruption that has proven so pervasive, corrosive, and resistant to reforms. While the Chatham House paper focuses predominantly on the attempts to reform Ukraine’s system of crony capitalism, and the structural reforms needed to combat the entrenched interests of Ukraine’s major financial-industrial groups (FIGs), these efforts all play out against the tense geopolitical backdrop of continued Russian pressure against Ukraine as well as Ukraine’s halting progression towards further NATO and EU integration.

At her daily press briefing on September 1, White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki noted that, with respect to Ukraine’s NATO aspirations, “There are steps that Ukraine needs to take; they’re very familiar with these: efforts to advance rule of law reforms, modernize its defense sector, and expand economic growths. Those are steps that aspirant countries like Ukraine need to take in order to meet NATO standards for memberships. And we will certainly support their efforts to continue to do that.” Because Ukraine’s path towards Western integration is contingent on efforts to combat corruption, it is worthwhile to take some time to review the Chatham House research, as well as how the progress (or lack thereof) in implementing the respective reforms is having on Ukraine’s path towards further Western integration. As noted in the Joint Statement issued by the White House after the Zelesnkyy-Biden meeting on September 1, “Ukraine’s success is central to the global struggle between democracy and autocracy…Ukraine has achieved progress in building institutions with integrity and intends, with U.S. support, to continue to counter corruption, ensure accountability, safeguard human rights, realize the aspirations of its citizens, and create favorable conditions for attracting foreign direct investment and driving growth.” It is therefore useful to examine the efforts that Ukraine has made so far, along with the ways the international community, and specifically the United States and European Union can go about aiding the Zelenskyy administration in not only combating corruption, but making the changes required for Ukraine to join NATO and the European Union.

Systema – Crony Capitalism in Ukraine

Before looking at Ukraine’s efforts to combat corruption under President Zelenskyy, Lough first tries to provide a reader with an understanding of the overall state of corruption in Ukraine since the late 1990s. Lough argues that crony capitalism in Ukraine, “functions based on a deeply integrated network bound by shared interests described here as systema, but known more commonly in Ukraine as oligarkhiya,” and that while variations of the model exist around the world, and unlike systema’s Russian counterpart, Ukraine’s corruption is rampant due to the absence of a strong state. In such a corrupt system, Lough argues, the common features of governance are high concentrations of capital in a small number of politically connected business hands, institutions that siphon public money at the expense of the public, low transparency, limited accountability, and weak rule of law. This corruption results in undermined democratic governance, distorted economies, and criminal/corrupt practices in public policy, favoring wealthy business interests. The author also notes that the ability of these major financial-industrial groups to put their interests above those of the public is not merely state or regulatory capture but rather a more symbiotic relationship between business and political officials, each of which needs the other to sustain a system which allocates resources entirely for their benefit, and not the public’s. Lough, therefore, argues that Ukraine constitutes what some refer to as a “limited access order”, wherein a ruling class artificially restricts both political and economic competition in order to accrue wealth. Such a system relies on corrupt politicians passing laws which are favorable to business interests, while also overseeing their implementation. In exchange, politicians receive both campaign financing as well as use of FIG media assets to further their electoral campaigns. Furthermore, the author argues that, over time, this corrupt system not only increases economic costs to the country by reducing competition, it creates a situation where large swathes of certain business sectors become dominated by certain politically connected businesses. For example, Lough notes that in 2015, politically connected businesses, which account for around 1% of companies in Ukraine, owned more than 25% of all assets and had access to over 20% of all debt financing in the country, and that in the capital-intensive mining, energy, and transport sectors, politically connected business accounted for 50% of assets and 40% of debt financing. This excessive amount of consolidation in these sectors not only has a deleterious effect on the Ukrainian economy, as it promotes rent seeking over wealth creation for the public, but it ends up capturing huge expanses of the workforce, who become just as dependent on the corruption to maintain their lifestyles, and therefore become as resistant to any changes in the status quo as the billionaire oligarchs.

All of this has led to a situation where, despite President Volodymyr Zelenskyy running on a platform that promised economic reform, he has had a difficult time dismantling systema, including efforts by the Constitutional Court of Ukraine to block judicial reforms, which paralyzed the work of the National Agency for Preventing Corruption.

To better understand the influence of corruption on Ukraine’s governance, Lough proceeds to describe the four pillars underlying systema, including: a penetration of government decision-making via senior officials who favor and benefit from their connections to big business; undue influence over the legislative process including paid-for support of MPs with direct or indirect business interests; undue influence over law enforcement and the judiciary through the appointment of loyal bureaucrats, and bribery of those bureaucrats; and control of the media through ownership of the country’s primary news/media outlets, which control the public exposure of politicians. In Ukraine, major financial-industrial groups own vertically integrated businesses spanning multiple sectors including agriculture, banks, mining, and media, and in the past, have proven resistant to change, because of a strong motivation to coexist as long as members do not rock the boat or try to gain exclusive control over the entire system. For instance, Lough offers the example of former President Viktor Yanukovych, whose “clan” of business associates violated these rules by attempting to consolidate his various business interests under family control while using Yanukovych’s political control to push out competitors. Lough argues that this destabilized systema and resulted in Yanukovych losing the support of his fellow oligarchs, which likely exacerbated the problems Yanukovych experienced after Ukraine signed an EU Association Agreement in 2013, resulting in the Euromaidan movement and his ultimate ouster from the presidency as well as the country.

Systema’s Structure

Lough notes that the Ukrainian systema is both pervasive and insidious, taking in not only business figures, but mid-level government officials, members of parliament, managers of state-owned enterprises, as well as the low level officials who collect day-to-day bribes. Furthermore, he notes that the corruption is not just centered in the capital of Kyiv, but present at the regional level, benefitting both local elites and their cronies in local councils such as the mayors of Kharkiv and Odesa. To Lough, this all results in a vicious cycle of reduced competition, resulting in weak institutions, poor legislation, and the absence of the rule of law, which merely feeds corrupt practices, which not only starts the cycle anew, but proves to be a persistent barrier to entry into top-level politics for independent actors. This is due to the country’s politics having become merely a competition over which candidate has the greatest financial resources. To illustrate this point, Lough points to the 2019 presidential campaign, where the 3 highest polling candidates each spent between $5-$21 million, mostly on television ads, compared to Poland, where GDP per capita is four times higher, which saw campaign spending by candidates in the 2015 presidential election spend a combined $4.8 million. The author does note that while Zelenskyy was elected as an outsider who campaigned on taking on the rampant corruption—indicating that there are large portions of the electorate that are clearly tired of the status quo—there is no general agreement from the ruling class about a need to change the way the country is governed, as seen by the return of Ihor Kolomoisky in 2019 on the eve of the presidential election and the re-election of Putin ally Viktor Medvedchuk to parliament the same year. Though Kolomoisky has since been publicly designated as an oligarch by the U.S. State Department, and Medvedchuk has been sanctioned by the Ukrainian government and is now under house arrest on charges of supporting separatists in Donetsk and Luhansk, Zelenskyy’s trust levels were still underwater as of July polling data, and his disapproval rating has grown to over 50%. While his polling numbers have rebounded to September 2020 levels, it does show that, despite his attempts to take on systema, a reformer like Zelenskyy faces numerous institutional obstacles which could derail his attempts at reform.

Systema in Action – Banking, Energy, Transport, and Healthcare

The Chatham House report then proceeds to a detailed look at systema’s impact on the banking, energy, transport, and healthcare sectors. The 2014-2015 banking crisis, coming immediately on the heels of Russia’s annexation of Crimea, saw the value of Ukraine’s currency, the hryvnia, fall precipitously in value against the dollar, as foreign currency exchanges plummeted to just $5.6 billion in February of 2015. This prompted a $17.5 billion bailout by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and a requirement that Ukraine nationalize its largest bank, PrivatBank, in order to address the bank’s recapitalization, which was required due to the bank’s risky lending practices under its owner, Ihor Kolomoisky.

However, Kolomoisky, the U.S.-designated oligarch, did not give up his bank without a fight, filing, as the Chatham report notes, hundreds of lawsuits against the nationalization, threatening the credibility of banking reform as a whole in Ukraine. The authors also point to the Verkhovna Rada blocking a 2018 reform mandating the introduction of independent supervisory boards at Ukreximbank and Oschadbank, an issue that was only recently resolved, despite IMF requirements for greater transparency at state-owned banks. This resistance, coupled with the 2019 attack on Valeria Gontareva, the ex-head of the National Bank of Ukraine who ordered the nationalization of PrivatBank, illustrate the lengths that systema interests will go to prevent an upsetting of the status quo when it comes to the well-heeled Ukrainian banking sector.

The Energy sector, which Lough notes has been the greatest source of rents income over the past three decades in Ukraine, has also seen its share of influence from systema, specifically in the field of natural gas production. In particular, Lough notes that until 2014, major FIG influence over the energy industry resulted in government policy favoring the import of Russian gas over domestic production, with illicit arbitrage schemes exploiting the price differential between the high market prices that industry paid and the subsidized gas prices that homeowners paid. As argued by Anders Åslund at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, in his book, Ukraine: What Went Wrong and How to Fix It, “Initially this arbitrage took place between Russia and Ukraine but today it is primarily within Ukraine. The government has financed this boondoggle of the rich and powerful with price and enterprise subsidies, provided state guarantees, and forgiven nonpayments. Inefficient state energy corporations governed poorly and not subject to public audits aggravate the corruption.” Furthermore, Lough notes in the Chatham House report that, “Gas traders ‘captured’ the national regulators to create this differential,” and that, “such practices not only distorted the gas market…they also had profound national security implications by creating a dangerous dependency on Russian gas. By 2014, [state-owned oil and gas company] Naftogaz had amassed a deficit equivalent to 5.7 per cent of GDP.”

While reforms at Naftogaz led to a cessation of gas supplies from Russia, ending of huge arbitrage margins, and greater transparency in company dealings, such cleaning up of the energy sector was not accomplished without resistance. As asserted by Edward Chow of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, “The fact is there was no unity of purpose on energy reform among Ukrainian authorities since 2014. Control over energy assets continued to be contested by different political interests inside the government.” Specifically, as noted by U.S. Senator Roger Wicker in a 2018 letter to then-U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions, arguing for the extradition to the United States of Ukrainian oligarch Dmytro Firtash, “Under Ukrainian law, Ukraine’s state-owned gas company, Naftogaz, is obligated to sell gas to [Russian] intermediaries, which are intended to purchase this gas and resell it to end-users. Knowing this, Firtash accepts the gas and sells it to end-users, but he refuses to pay Naftogaz and pockets the revenue. This scheme is estimated to have cost Ukraine $2 billion thus far, with $1.5 billion going directly to Firtash, which he uses to finance his legal fight against extradition.” Moreover, in addition to simply using these ill-gotten funds to fight his extradition case, Firtash was also able to continue having a nefarious impact on the Ukrainian energy sector. According to a 2018 report from the Atlantic Council’s Oleksandr Kharchenko, “Despite living under house arrest in Vienna and facing extradition charges by the United States for international crimes, Firtash is able to use his connections to manipulate multilateral organizations in order to gain personal profit; at the same time, he is fueling corruption in Ukraine’s energy sector, utilizing a corrupt system of gas intermediaries inside Ukraine,” and that, “due to the lobbying of Firtash’s representatives, the introduction of market reforms was postponed for another year.” However, Lough notes that the June 2021 imposition of sanctions on Firtash by the Zelenskyy government suggests that Firtash’s position has weakened over time.

Lough then proceeds to an analysis of the transport sector, which, though largely state-owned, still feels the pernicious effects of FIG and systema influence, resulting in direct losses of an estimated $5 billion per year, according to the Ukrainian Institute for the Future, in their 2018 report, “The Future of the Ukrainian Oligarchs”. In this sector, Lough notes that oligarch influence has led to a number of undesirable outcomes. For instance, two of the main beneficiaries of systema’s influence on the transport industry are Rinat Akhmetov’s SCM and Kostyantin Zhevago’s Ferrexpo. Akhmetov’s System Capital Management, whose largest interests are in mining and steel, and Zhevago’s Ferrexpo plc, which is the world’s third largest exporter of iron ore pellets, are both heavily dependent on the bulk transport of commodities by rail, due to the poor conditions of Ukrainian roads. However, Lough notes, that, as these commodity firms are so heavily dependent on the cheap movement of large amounts of heavy goods, it has seen FIGs endeavor to drive down the costs of rail construction, which has left the railway system in Ukraine in a truly deplorable state, with shortages of locomotives creating bottlenecks for the entire system and a bloated payroll which consumes an inordinate amount of operational funds. Furthermore, Lough notes that these oligarchs also profit from participation in tenders to supply goods and services to Ukrainian Railways (Ukrzaliznytsia), with Akhemtov’s Metinvest supplying rail and former President Petro Poroshenko supplying fuel.

In terms of aviation, Lough notes that Ihor Kolomoisky controls figures overseeing the management of Boryspil airport, the country’s largest, and, prior to the decision by low-cost carrier Ryanair to begin flights out of Boryspil, Kolomoisky’s Privat Group controlled 89% of all domestic Ukrainian airline capacity. Further, the Chatham House report notes that before the pandemic hit, around 30% of aviation fuel in Ukraine was supplied by Kolomoisky’s Kremenchug refinery.

Finally, the Chatham House report moves on to the field of healthcare, which is more competitive than banking, energy, or transport sectors, with no single company possessing more than 6% of the sector, and the largest financial-industrial groups largely absent. However, it too still feels the nefarious influence of systema. Here, Lough notes that healthcare firms had, prior to 2015, manipulated the tendering process for the supply of equipment and medicines through collusion between government officials and the companies supplying healthcare supplies. What resulted was the Ministry of Health spending around 40% of its funding on “black cash” or, the additional markup on drug and equipment prices. Though reforms were initiated between 2016 and 2019 under the leadership of acting Health Minister Dr. Ulana Suprun, which saw the creation of a, “new eHealth system and web-based NHSU dashboard [which] provide continually updated, transparent data on delivery and financing of care and adherence to standards, dramatically narrowing the space for corruption,” and the fact that, “the old model of financing hospitals per bed was scrapped. As of April 2020, hospitals are reimbursed based on the illness and conditions they actually treat…” In addition, the Atlantic Council’s Judy Twigg submitted that, “before the reform, there wasn’t reliable information on the number of medical institutions in the country…Nobody knew how many patients needed treatment for what conditions, or what medical services were being performed where.”

However, special interests that lost out because of the removal of manipulative pricing schemes were quick to lash out, resulting in attacks on Dr. Suprun’s authority by Kyiv’s Regional Administrative Court as well as anti-reformist groups in Ukraine like the Opposition Bloc, Batkivshchyna, the Radical Party, as well as some members of parliament, led by MP Ihor Mosiychuk. All of this eventually saw Suprun’s ability to make decisions suspended by the Regional Administrative Court in Kyiv and the State Bureau of Investigations opening a criminal case against Dr. Suprun in order to waste her time and that of her staff, paralyzing the ministry in its attempts to implement reforms. Further efforts by systema to interfere in the healthcare sector were seen during the pandemic, where pharmaceutical companies and their distributors lobbied the Zelenskyy government to not extend a system for the outsourcing of medicine procurement to international agencies that was due to end in 2020. These efforts failed, but the provision of COVID-19 vaccine was stalled because of internal squabbles between the Ministry of Health and the country’s Medical Procurement Agency over how to proceed with procurement negotiations. However, a law allowing the government to bypass normal procurement procedures in a pandemic scenario does open up the process for further corruption, and indeed, the pandemic saw Ukraine purchasing, “disinfectants and medical masks at inflated prices, and the municipal consultation and diagnostic clinic significantly overpaid on PPE.”

Agriculture: A Counterexample

Lough then proceeds to offer the example of the agriculture sector in Ukraine, which, despite being the, “best prospect industry sector” for Ukraine, according to the International Trade Administration, is not dominated by the same large business interests that control so much of the banking, energy, transport, and healthcare sectors. However, the reluctance of prior Ukrainian governments to permit the free buying and selling of agricultural land has favored the development of large agro-holdings, controlling over 50,000 hectares or more of land, with some able to secure access to land on decades-long leases. Lough argues that even though these agricultural holding companies control less than ¼ of arable land, they end up exercising undue influence over legislation and market rules. At the national level, Lough offers the example of Vitaly Khomutynnik, who is a shareholder in Kernel and also has business ties to Ihor Kolomoisky, one of Ukraine’s largest agro-holding companies, and also a member of the Verkhovna Rada’s Tax Committee in 2018 when it pushed through legislation favoring Kernel.

However, Lough notes that despite the size and influence of these agro-holding firms, international pressure by the IMF has resulted in a lifting of the ban on the sale of farmland. Combined, this international and domestic public pressure to do something about the concentration of land ownership resulted in the new law which allows Ukrainians to buy and sell up to 100 hectares as of July 1 2021. Though the law is ultimately rather meagre, it does illustrate the fact that real reform is possible in economic sectors where the largest FIGs are absent.

Systema and the Media

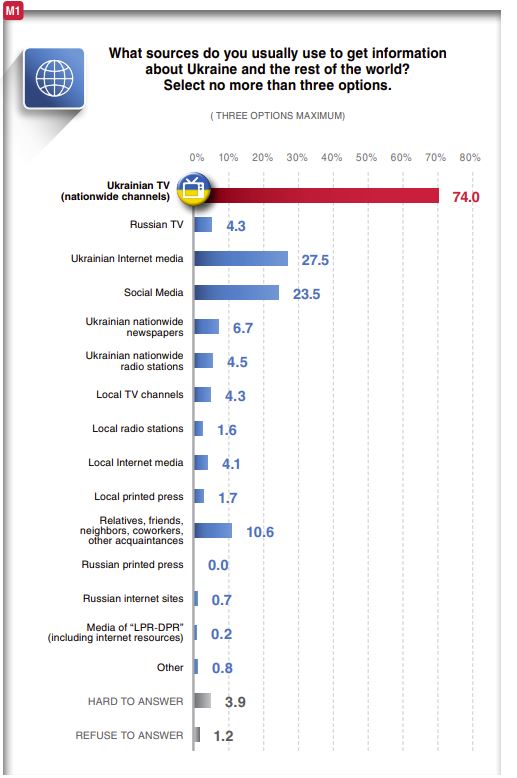

The Chatham House report’s penultimate chapter then takes a look at the role of the media in maintaining the oligarch-dominated status quo. Here, Lough points out that, in Ukraine, the four largest FIGs own 15 of the most popular television channels as well as the most popular newspapers, radio stations, regional television stations, and internet media. These companies and their owners StarLight Media (Viktor Pinchuk), Media Group Ukraine (Rinat Akhmetov), 1+1 Media (Ihor Kolomoisky, Viktor Medvedchuk, Ihor Surkis) and Inter Media Group (Dmytro Firtash, Valeriy Khoroshkovskii, Serhiy Lyovochkin) have the ability to reach over 75% of Ukraine’s television audience, giving them nearly total market reach. Furthermore, as noted by a 2016 study by the Institute of Mass Information and Reporters Without Borders, this means that Ukraine’s television market is characterized as High levels of audience concentration. In addition, Ukraine also experiences similarly high levels of audience concentration in radio media. This comes despite the fact that these media outlets are frequently loss-leaders for their owners, with Lough noting Inter Media Group having lost $70 million in 2012. However, what these firms lose for their owners in terms of operational losses, they more than make up for in their ability to reach voters and politicians with their messaging. Furthermore, the dominance of these four media groups illustrates the fact that it would be hard to run a political campaign in most of the country without the ability to advertise on one or more of these platforms, giving their owners enormous influence over the political process.

In practical terms, the Chatham House report notes that these media firms are particularly difficult to regulate under Ukraine’s constitution, as while the president is in charge of nominating the head of the national television and radio licensing body, parliament is still required to approve of the appointment. Further, a draft media law that has been under discussion in parliament since early 2020 is the work of several individuals in parliament that are connected with these aforementioned media groups, meaning that whatever legislation emerges from this process will ultimately be too weak to make a real difference.

Conclusions

The final chapter of the Chatham House report closes with a number of conclusions and suggestions for Ukraine’s international partners. Lough notes that there have been disruptions to the interests of systema in the fields of energy, banking, and healthcare, but that regression is still an ever-present danger. The author notes the summary firing of Andriy Kobolev as the CEO of Naftogaz in April of this year, which was enabled only after Ukraine’s Cabinet of Ministers dismissed the Naftogaz supervisory board that should have been in charge of determining Kobolyev’s termination. This was called a “legal manipulation” by Naftogaz management, though Acting Energy Minister Yuriy Vitrenko argued that Kobolev had been terminated entirely due to the unsatisfactory UAH 19 billion loss that the company had posted in 2020. However, it is easy to see how this type of interference by the Zelenskyy administration is immensely concerning in light of the susceptibility to corruption the energy field has shown in the past.

Further, Lough notes that in a 2020 Ukraine in World Values Survey found that large portions of the country’s citizens find that state authorities (72.2%) and civil service providers (67.1%) are corrupt. The amount of citizens that find state authorities corrupt puts Ukraine close to Greece (73.7%) and Romania (69.0%), two countries that are widely regarded as some of the most corrupt in Europe. While Lough does acknowledge the fact that Zelenskyy’s election as a complete political outsider and the large number of first time MPs elected to the Verkhovna Rada in 2019 does suggest that a large segment of society does desire change, a lack of parties that are deeply rooted in civil society that are committed to true reform means that these aspirations are difficult to translate into reality. In addition, Lough argues that Zelenskyy appeared to side with systema in the spring of 2020 when he criticized the number of foreigners on the supervisory boards of state companies and pushed for the resignation of the head of the Anti-Monopoly Committee. Adding to these concerns are the issues voiced by former U.S. special envoy for international energy affairs for the Obama administration, Amos Hochstein, in stepping down from the board of Naftogaz. In his resignation letter, announced in an October 12 op-ed in the Kyiv Post, Hochstein referenced a deal made by the Ukrainian government to import liquefied natural gas (LNG) from a relatively unknown U.S. company and name one of its executives to the Naftogaz supervisory board. In his piece, Hochstein stated that, “I can no longer stand by and be used to endorse this negative trend, and it’s why I must voluntarily leave the board. Supervisory boards cannot include members whose values are not in line with the reform and good governance agenda. Supervisory boards must continue to be independent, strengthened, and protected from undue influence,” and that, “Naftogaz management’s successful efforts to create a new corporate culture, transparent mechanisms, and an adherence to international standards, was resisted at every step of the way. The company has been forced to spend endless amounts of time combating political pressure and efforts by oligarchs to enrich themselves through questionable transactions.”

Hochstein’s resignation came on the heels of Swedish economist Anders Åslund’s resignation from the board of Ukrainian Railways, when Åslund stated that, “many of our decisions are not being implemented by Ukrzaliznytsia’s management. Nor does the government give Ukrzaliznytsia reasonable regulatory or financial conditions to modernize and become efficient (unjustified land tax, tariffs set far under cost level, insistence on massive overstaffing, etc.). These circumstances leave the company in a precarious financial situation.” Further, Åslund also noted that his participation on this supervisory board exposed him to legal risks without promised liability insurance from the Ukrainian government and the fact that he had not been paid in five months, his concerns about the way the government was dealing with the national railway company.

To promote the rule of law, Lough contends, Ukraine’s international partners have placed a huge emphasis on anti-corruption bodies including the National Anti-Corruption Bureau (NABU), The Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office, and the High Anti-Corruption Court. However, the NABU and the Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office have been hampered by the absence of a properly functioning judicial system, and that judicial reform, up until very recently, has been hampered itself by the country’s flawed legal system.

The author argues that international partners that have done their own governance reform can offer their own reference points for Ukraine, but whatever the country’s leadership decides on will require deep structural reforms to go along with civic activism and preventive measures to restrict the future growth of corruption. Here, Lough argues that reducing systema’s influence will require creating a paradigm where rent seeking is more difficult and less profitable. To make real inroads, Lough argues that Ukraine’s international partners need to tie their financial support to real judicial reform; the IMF and EU need to impose strict conditionality to make possible the creation of real anti-corruption infrastructure that is able to execute the deep judicial reform the country needs; and that the country will need large amounts of financial support over the next two years in order to service its foreign debt and cope with the economic consequences of the pandemic. Finally, he also argues that Western countries must resolve to investigate suspected money laundering by the beneficiaries of rent seeking and corruption in Ukraine, specifically those that buy UK real estate or use EU banks to protect their assets.

While Lough’s analysis of the situation and recommendations are both spot on, there are also a number of other measures that Western governments might want to pursue when it comes to supporting Ukraine in its efforts to battle the corrupt influence of systema and become a more fully integrated partner in Western institutions. Furthermore, getting to a point where corruption is not a major influence in Ukraine will be a tough road. As noted by Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian affairs, George Kent in a recent interview about Ukraine, “To succeed, to get to this point [of ‘de-oligarchization’], is difficult.”

Specifically, Western governments need to address the fact that their demands for Ukraine are far too often nebulous, resulting in the Zelesnkyy government being unable to truly satisfy the specific U.S. and European demands that are required for Ukraine’s EU or NATO accession. As argued by Lithuanian President Gitanas Nausėda in remarks to the Ukraine Reform Conference on July 7, “We know that integration is a two-way street. Ukraine needs definite end-goals to seek and to plan for, while the international community expects assurances on the continuation of a sustainable and consistent reform process.” Leaving aside the fact that reform processes tend not to be consistent and fluctuate between periods of incremental and then rapid change, the desire from the Lithuanian president for better goals for Ukraine is clearly something that needs to be addressed by the EU. Furthermore, Zelenskyy agrees, arguing at the same conference that, “I agree that the key to a positive solution to our Euro-Atlantic aspirations is…the success of our reforms. And we will continue to do everything to accelerate the pace of reforms, including within the framework of the implementation of annual national programs under the auspices of the Ukraine-NATO Commission. But today we would like to receive an exhaustive list of reforms, the implementation of which will allow us to move on to the next stage of our integration with NATO.”

Such an exhaustive list of reforms, possibly provided under the auspices of Ukraine’s NATO Membership Action Plan, could result in a more specific listing of issues that Ukraine needs to address in order to achieve greater Western integration, giving Zelesnkyy more leverage over the forces of systema in the country, as it would provide him with a list of specific action items that need to be changed, and he could therefore go directly to the public when corrupt forces in the country push back against these needed reforms. At the minimum, it would result in a better, more specific Annual National Programme than the one provided by the Ukrainian government in 2020, which is full of nebulous requirements such as, “1.2.1.1. Coordinated, coherent and consistent state anti-corruption policy in the public sphere” which is followed by a listing of sub-requirements like making “fair behavior in the public sector…a generally recognized norm…” despite there being no concrete definition of “fair behavior” or “public sector” and a “deadline” of 2020 with no further information about achieving such a amorphous goal.

Instead, what the U.S. and European governments need to provide Ukraine with is a detailed analysis of any areas in which the U.S. has recognized a fault or a deficiency, along with the specific conditions under which Ukraine will be considered to have successfully addressed those issues, and a realistic timetable for Ukraine to make these changes. For instance, in terms of judicial reforms, instead of the following, hazy requirements that “The Judicial Corps has been updated and new mechanisms have been introduced to promote the integrity of judges,”, it might instead read: “As the High Qualification Commission of Judges and High Council of Justice are the two main judicial governance bodies, independent international experts must participate in the future selection of both bodies.” Similar, more specific recommendations should be made for each action item that Western governments wish Ukraine to make changes to.

While providing an exhaustive list of reforms would be difficult, Ukraine’s annual national program (ANP) could provide Western governments with a jumping off point to begin their analysis, providing more specificity to each one of Ukraine’s listed goals and a clear understanding of when Western governments will consider these goals to be met.

Additionally, other ways that the West might attempt to better assist the Ukrainian government in combating corruption are by directly providing assistance in the areas of the Ukrainian economy where corruption is most prevalent. For example, in the energy sector, Ukraine’s reliance on the transit of Russian gas has long been a threat to the country’s national and economic security and the imminent completion of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, which will bypass Ukraine, has only increased Ukraine’s anxiety, despite assurances from European leaders that Russia will not be able to use gas as a weapon. Furthermore, there are indications that the Nord Stream 2 pipeline could be eventually repurposed to supply clean hydrogen between Russia and Germany, which would clash with future Ukrainian desires to tap their unexplored hydrogen production potential.

While one of the key actions of the 2020 EU Hydrogen Strategy is to, “promote cooperation with Southern and Eastern Neighbourhood partners and Energy Community countries, notably Ukraine on renewable electricity and hydrogen,” Nord Stream 2’s construction threatens that element of the strategy. Therefore, there are a number of steps that the EU and the U.S. can take to assist Ukraine in not only combating corruption in its energy sector, but in helping Ukraine transition to a greener economy. As noted by the Jamestown Foundation’s Sergey Sukhankin, one project that is already under consideration is the Green H2 Blue Danube project, aimed at linking Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, Germany, Hungary, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia with Bosnia and Herzegovina, Moldova, Montenegro, Serbia, and Ukraine, which would create a continent-wide supply chain for hydrogen that can be transported to Europe. Helping to fund such a project would not only assist Ukraine’s green transition, which Germany has already vowed to support, but would, ideally, provide reasonably priced energy in a new sector that is not already captured by established FIGs.

Another option to assist Ukraine in its energy sector would be to aid in modernizing Ukraine’s electricity grid. As noted by Lough in the Chatham House report, in 2020, Ukraine ranked just 128th out of 190 countries for “getting electricity” in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Rankings. To that end, Europe could do more to assist Ukraine in joining its electrical grid with the EU’s, a project that is already underway, but could use more funding to make it happen in a timely fashion. As Germany and the United States have already issued a Joint Statement on supporting Ukraine’s future energy security, along with a pledges of public and private support reaching up to $1 billion for the Green Fund for Ukraine, it only makes sense to focus a large deal of the funding into areas in which the West can get a kind of double-return on investment, in that investment supports Ukraine’s green energy transition while also helping it move away from the provision of energy by entrenched, corrupt interests inside the country.

If Germany is committed to moving forward with Nord Stream 2, despite the numerous warning signs that the project may threaten European security through a dangerous increase in dependence on Russian gas, will certainly have serious economic ramifications for Ukraine, and even poses a threat to European governance, it will need to reckon with these consequences, and assisting Ukraine with its path away from systema and towards a secure, green future is a good first step on that path.

In sum, Ukraine, under Volodymyr Zelenskyy, has made great strides towards meeting the aspirations of the Euromaidan protesters and combating the nefarious influence of systema on the country’s economy. However, without more input from the West, it is unlikely that Zelenskyy will have the leverage to push through all of the reforms needed in Ukraine. A failure here would be devastating not just to the majority of Ukrainians who desire more integration with the West, but it would be damaging to Western credibility, as Ukraine would become yet another country mired in the seemingly never-ending NATO and EU membership application processes. Furthermore, after the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, it is even more vital that the U.S. not abandon a partner whose government actually appears willing to put in the work needed to combat corruption in the country. While the efforts under Zelenskyy have been far from perfect, and he has exhibited his own tendencies to favor those he can directly influence and punish those who oppose him, he still appears more amenable to anti-corruption measures than figures like Ashraf Ghani or Hamid Karzai ever were. Furthermore, despite the fact that his approval ratings only hover around 50%, Zelenskyy is still viewed as the second best Ukrainian president since independence 30 years ago, and the number of those optimistic about Ukraine’s future continues to increase, while the share of those skeptical about the future continues to decrease. If the West misses out on the chance to engage with him seriously on reform, it may find that Zelenskyy was its last chance.

3 thoughts on “Dismantling ‘Systema’ and Bringing Ukraine More Fully into the Western Orbit”