April 29, 2022

The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs this week, in their weekly Humanitarian Impact Situation Report for Ukraine, noted that, “the ongoing war continues to exacerbate a massive humanitarian crisis,” and that, “over 24 million people – more than half of Ukraine’s population – will need humanitarian assistance in the months ahead.” Furthermore, the war has, “caused the world’s fastest growing displacement crisis since the Second World War, uprooting nearly 13 million people.”

However, the war’s effects are not only confined to Eastern Europe. As discussed a few weeks ago in these pages, the Russian war in Ukraine is truly a global problem, with important implications for China, India, Pakistan, Israel, Venezuela, and beyond. However, the war also poses major questions for governments in the United States and Europe, as they grapple with Russia’s military and economic escalations in Ukraine. Specifically, Western governments will need to resolve questions about how to manage Russian escalation during the war; how the war will affect the United Nations system and the NATO alliance; and what will need to be done to put Ukraine back up on its feet after the war’s conclusion. Moving forward, the war in Ukraine will need to transform not only how Western nations respond to Russia on the battlefield, but how they address the problems posed by Putin’s Russia in between crises, as well.

Managing Escalation

However, the first way in which the war in Ukraine must transform Western nations’ understanding of and response to Russia is indeed on the battlefield. Specifically, NATO members will need to better understand how to respond to Putin’s escalations in Ukraine; as Putin comes to the realization that Russia has already failed to achieve its war aims in Ukraine, he will likely continue to escalate his attacks on Ukraine’s civilian populace. In response, the U.S. and its European NATO allies will need to properly manage these dynamics, or else they risk either giving in to Putin’s reckless behavior or encouraging him to escalate even further in order to get what he wants.

Taking that into consideration, it is useful to examine an April 21st report from the Atlantic Council’s Richard D. Hooker, Jr., “Climbing the ladder: How the West can manage escalation in Ukraine and beyond,” which argues that escalation in Ukraine can be grouped into four discrete “rungs” of action, the triggering of which will depend on Putin’s view of how well or poorly the campaign in Ukraine is going at the present moment. Hooker argues that the major triggers for escalation up the ladder would be an assessment that the campaign has temporarily stalled; that it has stalled outright; or that a total defeat is near.

All of those scenarios might see Putin decide to increase the pressure on Ukraine and the West so that they capitulate or come to some form of agreement that is acceptable to Russia. However, while Putin may not require the total annexation of Ukraine in order to consider the military campaign in Ukraine a success, he will undoubtedly desire concessions that the West and Ukraine’s government are unwilling to give. Therefore, it is vital to understand where and how Putin might escalate the military operation in Ukraine, and determine—in advance—what reactions NATO members should take to such provocations.

While the “first rung” of Hooker’s escalation ladder has likely already been reached—as Putin witnessed the initial failure of his invasion and began to direct the indiscriminate attacks on civilians—there is room for the threat to intensify, as Russia has already begun to threaten Ukraine with nuclear attacks. Furthermore, Russia has already conducted major cyberattacks to support its military strikes in Ukraine, yet another indication that Putin is ready to move up the escalation ladder in response to the overall lack of progress by the Russian armed forces.

Hooker’s “second rung” could be reached if Russian forces fail in its efforts to encircle the Joint Force Operation (JFO) in Donbas and a long-term stalemate seems likely. At this rung of the escalation ladder, Hooker argues, Russia is likely to expand military conscription, mobilize reserves, and strip remote areas of their garrisons in order to supplement and augment the roughly 15,000 troops that Russia has lost in the war so far. Furthermore, in the Black Sea, where Russia has naval dominance due to the strictures of the Montreux Convention, Russia could look to disrupt shipping by boarding commercial vessels at sea, bombarding coastal cities, and interdicting coastal motorways and rail lines.

Economically, Putin may have already entered the second rung of the escalation ladder, as he has already endeavored to increase the number of troops at his disposal, and has begun to cut off the delivery of natural gas to Poland and Bulgaria—which may be merely a warning sign of more cuts to come for Central and Eastern European nations. Furthermore, Moscow has already taken steps to nationalize the assets held by U.S. and EU countries in Russia, which has already caused the flight of nearly 400 Western companies from the country. However, as a world leading producer of fertilizer, wheat, palladium, and nickel, Russia still has enormous impact on global commodity markets, and the removal of its products from those markets damage foreign economies as well as Russia’s.

A “third rung” of Hooker’s escalation scale could be arrived at if sanctions continue to eat into Russia’s economic growth, casualties and attrition mount, and Putin’s chances for anything he can sell to the Russian public as a decisive victory shrink. According to Hooker’s report, such a scenario could trigger even more unrestrained assaults on cities, with more widespread use of thermobaric weapons; a redoubled Russian efforts to encircle and eliminate Ukrainian troops in the JFO area; a demonstration or test of a low-yield tactical nuclear weapon to raise the stakes for Zelenskyy and the West; greater targeting of Ukraine’s communication infrastructure; heightened rhetoric about the existential nature of the war in Ukraine; and a disruption of oil and gas shipments to Europe in order to pressure European leaders to cut off support to Ukraine.

Finally, Hooker’s “fourth rung” could be reached in the case of a prolonged stalemate or if Putin views military defeat as imminent. In either scenario, Putin—viewing the war in Ukraine in existential terms not only because of a tendentious and fallacious belief that Ukraine is full of Nazis, but because failure to achieve his goals despite Western sanctions could possibly force a regime change in Moscow—would likely determine that he had little left to lose, and would subsequently be liable to do just about anything in response. In such a scenario, Hooker argues that Putin would have a few major options at his disposal, including: cyber tools, weapons of mass destruction—including nuclear weapons—and attempts to destabilize areas outside of Ukraine.

In terms of cyber tools, Putin could target critical national infrastructure such as transport and power grids—including Ukraine’s fifteen nuclear reactors—healthcare systems, government facilities, and the financial sector. When it comes to the use of weapons of mass destruction, Russia has already laid the groundwork for their own use of chemical weapons by falsely accusing the U.S. and Ukraine of conducting chemical weapons research on Ukrainian territory. Furthermore, there are allegations that Russia has already violated international norms, employing chemical weapons during the siege of Mariupol.

Putin may also decide to target areas outside Ukraine in order to sow more chaos and further complicate the regional picture. For example, there are already reports that Russia may be laying the groundwork for a false flag operation in the breakaway state in Moldova, setting the scene for Russian troops already stationed there to create a southern land bridge between Donbas and Crimea, allowing Russia to strangle Kyiv. Similarly, Russia might be prepared to shoot the Suwalki Gap, cutting off the Baltic states from Poland and linking up Russian Kaliningrad with Belarus and the rest of Russia’s territory. However, such a scenario is more likely to occur once Putin has already achieved success in Ukraine, has had time to regroup his forces, and can refocus his attention to another theater.

Finally, Putin ultimately has the option of escalating to the use of nuclear weapons in or around Ukraine. The Atlantic Council report argues that such a strike would likely take the form of a low-yield tactical nuclear weapon, or possibly a nuclear “accident” at one of Ukraine’s nuclear reactors. Though Hooker argues that a low-level nuclear attack would not necessarily escalate out of control, and could give Putin the leverage he needs to gain Ukraine’s submission, such an attack would even further isolate Russia from the international community—a pariah status that Putin may find impossible to shake off once it sets in.

Controlling Russian Escalation

Hooker’s report closes by offering a series of principles to guide NATO’s assessment of Russian escalation, along with steps to help prevent unwanted escalation in the first place. To begin, he argues that the West must continue to arm Ukraine, helping the Ukrainian armed forces either defeat Russia or at least draw it into a stalemate that does not allow Putin to declare victory.

Secondly, Hooker argues that if NATO does eventually intervene in the conflict, it must do so decisively, either setting up a no fly zone—which would involve shooting down Russian aircraft— or sending special operations forces and communications specialists to help train Ukrainian forces. While both moves would be escalatory and risk a full blown conflict between Russia and the West, they could be necessitated by credible allegations of genocide and further heinous war crimes perpetrated by Russian forces.

Hooker also argues that in order to forestall future Russian aggression, the U.S. and its European NATO allies should increase their forward presence in Eastern Europe, as countries such as Lithuania request greater reassurance. Along those lines, U.S. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Mark Milley has already proposed increasing the number of rotational forces at permanent bases in Poland and the Baltic states, and NATO has announced the formation of four new battlegroups to reassure allies in Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania, and Slovakia.

Hooker’s fourth recommendation is that the US and NATO must take clear stances on nuclear policy, arguing that articulating a hysterical fear of Russian nukes only emboldens Russian leadership, as they can use the threat of nuclear use as a cudgel to gain what they seemingly cannot win on the battlefield. As former U.S. Principal Deputy Director for National Intelligence David C. Gompert has recently stated in a Wall Street Journal op-ed, “the more the U.S. falls for Mr. Putin’s nuclear messaging, and the more we signal that the U.S. dreads nuclear war more than Russia does, the less restrained Mr. Putin will be in Ukraine, and the more Ukrainian lives will be lost.”

Hooker also recommends that the West employ economic tools as the primary offensive weapons against Russia. However, to make those economic tools effective, they must be used to their fullest extent possible. This means closing off loopholes for Russian banks in the energy sector, and barring Russian metals from commodity exchanges in London and Chicago. However, Hooker is careful to note that BRICS countries remain open to trade with Russia and are a key lifeline for the Russian economy.

The sixth recommendation in the Atlantic Council report is that Western nations need to be ready for Russian escalation in cyberspace. As mentioned above, Russia has already made extensive use of cyber tools during the war, correlating cyberattacks on Ukrainian telecom infrastructure while simultaneously conducting military attacks as well. A clear, early demonstration of the West’s cyber red-lines would be valuable so as to communicate to Russia that the West has similar tools at their disposal, and that Russia would be wise to keep theirs in their bag.

Finally, Hooker closes by arguing for sustained diplomatic unity amongst Western allies; though it must be recognized that Ukrainians will be the ultimate decision maker on when, why, and how to terminate hostilities. While the U.S. and its European NATO allies may be tempted to intervene in order to achieve a peaceful early resolution to the conflict, this is a war being fought by Ukrainians, and only Ukrainians are permitted to say when they have had enough. In the meantime, more votes condemning Russian aggression at the UN General Assembly, and successful votes to remove them from bodies such as the Human Rights Council are both strong ways to demonstrate international opposition to the Russian war in Ukraine.

Readying for the Long-Term

However, being ready for Russian escalation is not the only requirement for Western decision makers. They need to be better prepared for an extended period of tension with Russia under Vladimir Putin. In another recent report, “The Ukraine War: Preparing for the Longer-Term Outcome,” the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ (CSIS) Anthony Cordesman—with the assistance of Grace Hwang—argues that, “it is far too early to predict the ultimate outcome of the Ukraine War, but it is all to clear that no peace settlement or ceasefire is likely to eliminate a long period of military tension between the U.S. – including NATO and its allies – and anything approaching President Putin’s future version of Russia, nor will any resolution of the current conflict negate the risk of new forms of war. It is equally clear that the U.S. and NATO need to act as quickly as possible to prepare for an intense period of military competition and must create a more secure deterrent and improve their capability to defend against Russia.”

Indeed, one of the few clear outcomes in the first nine weeks of war in Ukraine is that whatever happens, the West must be ready to defend against a newly assertive Russia. Taking that into consideration, Cordesman’s report offers an interesting insight into how the U.S. and its NATO allies will need to better coordinate if they are to meet the challenge posed by Vladimir Putin. While the Russian invasion of Ukraine has spurred some forms of soul-searching by governments in Berlin, Helsinki, Stockholm, and Brussels, it is clear that more needs to be done to make up for years of cuts to and underfunding of European militaries, as readiness and modernization deficiencies have left NATO members unready to face a newly assertive Russia. Cordesman argues that European NATO countries will not only need to make up for years of underfunded militaries, but they will have to do so at a time when the impacts of inflation from the pandemic and the war in Ukraine will eat into whatever budget increases European parliaments do ultimately approve.

Cordesman’s report argues that in order to move towards a more functional and effective NATO, member states need to abandon the 2% of GDP spending guideline for NATO militaries. Such a determined focus on an abstract spending target not only obscured the fact that, in the years leading up to the war, Russian defense spending was dwarfed by NATO Europe alone, but it also did little to convince European publics that spending increases were warranted, as no real assessment of the threat posed by the Russian military ever accompanied the spending goals. Cordesman notes that not only did a majority of members still spend under NATO’s 2% guideline—with economic powerhouse Germany only spending 1.5% of its GDP on defense in 2021—but few countries possessed the modern equipment required for a fight against a peer competitor. Cordesman argues that when looking at weapons holdings; technology levels; and the command, control, computers, communications, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (C4ISR) systems of NATO members, it is clear that even countries that do meet the 2% goal frequently need to actually spend over 3% to offset aging weapons systems and steady cuts in military force size.

The CSIS report argues that, moving forward, NATO members need to pay better attention to information warfare; arms control; programming, planning, and budgeting (PPB); and force planning. Specifically, in the field of information warfare, Cordesman is actually not necessarily arguing for new technology to defeat Russia in cyberspace; rather he is advocating for states to provide better, unclassified, information to the public on the array of threats they face. Such information will help states justify to their domestic populations requests for greater military spending and modernization.

As part of states’ efforts to better inform their publics of the threats they face, Cordesman argues that countries need to make better use of net assessments, which the U.S. Department of Defense defines as, “comparative assessment of trends, key competitions, risks, opportunities, and future prospects of U.S. military capabilities.” Furthermore, as argued in “Net Assessment: A Practical Guide,” Yale’s Paul Bracken argues that, “net assessment tends to study issues that are important but overlooked,” and that net assessment attempts to prevent leaders from muddling through problems, as pushing through with poor understanding of the overall situation, “can produce a ‘tyranny of small decisions’, where responding to short-term pressures lays the groundwork for much bigger problems later on,” such as the UK’s refusal to acknowledge the dangerous rise of Hitler in the 1930s. Put another way, as argued by Yee-Kuang Heng in a 2008 paper for the journal Contemporary Security Policy, “net assessment incorporates the Sun Tzu adage of war: know the enemy and know yourself.”

However, as Cordesman notes, NATO has not conducted a robust assessment of either its own capabilities or Russia’s, though the creation of a new net assessment office was one of the recommendations made in the report, “NATO 2030: United for a New Era,” released in November 2020. If NATO planners had done so earlier, not only would they have recognized that NATO’s European members collectively outspend Russia all by themselves, but that when their spending is combined with Canada and the U.S., Russian defense spending only equals about 16% of the $1.113 trillion spent by the entire NATO Alliance. Therefore, it is not simply about getting European NATO members to spend more—though that may be a part of the equation—but about getting them to spend smartly, so that member states have the training and equipment to seamlessly coordinate their modernized forces for joint all-domain operations.

As part of this effort, Cordesman argues, states will need to abandon—or at least heavily supplement—grand strategic documents like NATO 2030 or the EU Strategic Compass, as their broad strategic frameworks obfuscate the problems that NATO and its members face in terms of modernization and interoperability. Vague, sweeping, strategic goals not only do not help NATO members meet the Russian threat, such pronouncements do not address the fundamental problem that many states lack the troops and equipment to act together coherently, effectively, and efficiently to achieve tactical, operational, and strategic objectives.

Therefore, what is required is a better way to bridge the broad outlines provided by NATO and EU strategy documents with, “concrete goals, numbers, schedules, and costs for procurement, allocation, manpower, force structure, and detailed operational capabilities.” While the Russian invasion of Ukraine has clearly prompted European leaders to focus on defense more than they had in the past few decades, the situation offers a unique chance for NATO member states to better coordinate their defense spending so that spending is not just harmonized alliance-wide, but that spending addresses key deficiencies in individual members’ militaries. As part of this, Cordesman proposes an integrated NATO planning, programming, and budgeting system, linked with a net assessment of the threat posed by Russia, that would allow NATO command in Brussels to review country-by-country military improvements in order to determine what more individual states need to accomplish.

As another part of this effort, Cordesman also proposes that the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency begin issuing new yearly editions of Russia Military Power, which was last published in 2017 and looks at the unclassified military data necessary to support a net assessment of Russian military capabilities. Such documents are still made available for countries such as North Korea and China, and a return to publishing Russia Military Power would be useful for NATO decision makers and academics alike as they assess the state of their and their rivals’ militaries.

The CSIS paper also argues that NATO member states need to set clear goals for improving the interoperability of their combat units, giving NATO the ability to harmoniously conduct joint operations across a range of domains including land, sea, and air, but also space, autonomous operations, and cyber warfare. Too often, the larger, more wealthy NATO members are relied on in these areas—as they are the only ones with the expensive platforms and enablers needed to conduct such activity—to the detriment of the alliance’s ability to integrate all member states troops in a major operation against a peer competitor such as Russia or China.

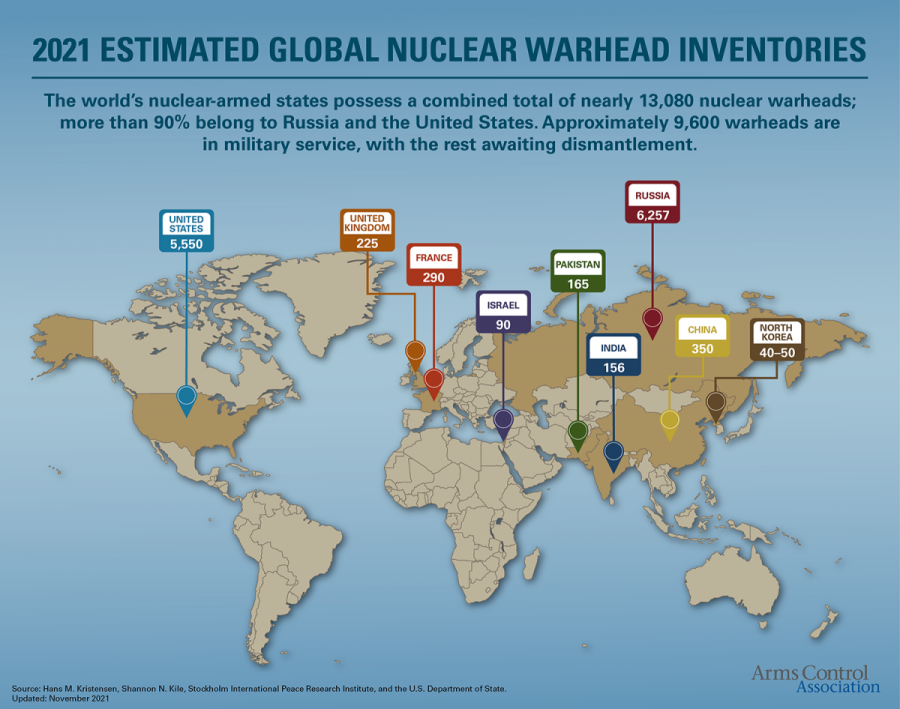

Finally, the Cordesman paper ends by arguing that NATO members need to be better prepared to respond to attacks by, and conduct their own assaults with, long-range precision fires, unmanned systems, and air platforms. Cordesman notes that while Russia’s Air Force has not exactly covered themselves with glory in its operations in Ukraine, it has not fundamentally altered Western nations’ calculus when it comes to the threat posed by Russian planes and missiles. As a 2020 Rand Corporation report on European Contributions to NATO’s Future Combat Airpower notes, despite NATO allies increasing investment in new aircraft and precision guided munitions, “European air forces may struggle to maintain platforms that are strained from rigorous deployment, in need of scarce parts, or nearing the end of their operational life.” Furthermore, as Cordesman notes, few European NATO members have long-range, conventionally-armed precision guided missile strike systems, and it will take time to remedy this, when Russia has already put a major emphasis on advanced, layered air- and missile-defense. This is in addition to the problems posed by Russia’s expanding and modernized nuclear arsenal, which are magnified when compared to France and the UK’s relatively small complement of nuclear weapons.

Ultimately, for Cordesman, the war in Ukraine, and the wake-up call it provided to European capitals is the perfect opportunity to do something that the Alliance should have done decades ago: conduct a fundamental review of the equipment, troop levels, technology, spending levels, and goals of each member state and their main rivals, and incorporate those findings into an overall assessment of what the Alliance is able to accomplish with today’s equipment. Not only would such an assessment provide a more complete picture of the threat posed by Europe’s main antagonist—Russia—it would give NATO members a better understanding of how they could respond in an eventual crisis.

The War’s Long Shadow at the UN

In addition to being a wake-up call for European NATO members, the Russian invasion of Ukraine also serves as an important warning to the United States, specifically in regards to how it behaves at the United Nations. As argued by the United States Institute of Peace’s (USIP) Andrew Cheatham, the 2000s saw a decline in U.S. participation in the global system founded after the end of the Second World War, as it failed to ratify the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, blocked appointments to the WTO, and withdrew from the Paris Climate Agreement.

It is amidst this U.S. withdrawal from the international system that Russia invaded Ukraine, with the UN Security Council (UNSC) seemingly powerless to do anything to stop the bloodshed. Therefore, as Cheatham argues in his piece, U.S. decision makers need to rebuild the case for U.S. leadership at the UN by: building a broad coalition of states to defend the liberal international order against an authoritarian onslaught from Russia or China; paying its unpaid membership dues so as to support UN peacekeeping operations; and recognizing that while the U.S. does shoulder the largest percentage of UN dues, that amount still pales in comparison to the cost of direct U.S. military engagement.

Another thing the U.S. might pursue in light of the war—and the subsequent failure of the UN Security Council to stop it—would be to pursue Security Council reform. With the five permanent UNSC members divided into rival geopolitical blocs the Council members’ veto power prevents real action on vital decisions like the war in Ukraine. One recommendation for reform comes from the Brookings Institution’s Kemal Derviş and José Antonio Ocampo, who suggest that Article 27 of the UN Charter be changed, eliminating the permanent member veto. Derviş and Ocampo suggest that instead, a supermajority of ⅔ of UN member countries could instead be used to override a Security Council veto. While such a move would undoubtedly be vetoed by Russia or China, a majority of countries might indeed support it, and it would allow the U.S. to reassert its leadership at the multilateral body and demonstrate its commitment to democratic principles over autocratic obstructionism.

In parallel to that effort, Cheatham proposes the U.S. strengthen other United Nations mechanisms for peace and security, including by increasing U.S. funding to the UN Peacebuilding Fund from the paltry amount it contributed between 2016-2020. The U.S. could also contribute more resources to the UN’s Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs, working with the UN Peacebuilding Commission and Peacebuilding Support Office, as well.

Finally, the USIP analysis argues that the U.S. needs to help build a stronger system of international accountability, so that Russian war crimes in Ukraine will be properly adjudicated by the international community. While acknowledging that U.S. ratification of the Rome Statute has historically been a non-starter, it is important to note that Congressional Republicans may be shifting somewhat on the ratification of the International Criminal Court’s founding document. In addition to ratifying the Rome Statute, Cheatham argues that that the U.S. and its allies should share declassified intelligence with international prosecutors; support efforts to collect open-source data as evidence of possible Russian war crimes; augment the capacity of international investigations by seconding Department of Justice staff to international courts; and by continuing the U.S.’ own investigations into alleged U.S. violations of international law, limiting room for allegations of American hypocrisy.

The War’s Long Shadow: Rebuilding Ukraine

Finally, despite there being seemingly no end in sight for the already horrific war, there must be some consideration about which countries will pay for the reconstruction of Ukraine once the war does finally end. As argued recently by the RAND Corporation’s William Courtney, Khrystyna Holynska, and Howard J. Shatz, understanding the particulars of the reconstruction challenge is vital. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, for example, the challenges to effective distribution of aid was a lack of a strategic vision, inconsistent execution, duplication of communications, low donor accountability, weak incentives for donors to cooperate, as well as personal conflicts. In Ukraine, those problems may range from lack of strategic vision from international donors to corruption and waste from the government in Kyiv.

The RAND Corporation commentary notes how former Ukrainian finance minister Natalia Jaresko—who led Puerto Rico’s financial oversight board after Hurricane Maria devastated the territory in 2017—has argued that in Puerto Rico’s recovery, the most important first step was to properly document and assess the damage, which is being accomplished in Ukraine via a Ukrainian government website. Currently, the World Bank estimates that the damage done to Ukraine has reached $60 billion already, and President Zelenskyy has argued that Ukraine will need $7 billion per month to make up for economic losses caused by the invasion. Furthermore, the Centre for Economic Policy Research has—by looking at both historical analogies and data on property damages and Ukraine’s capital stock—concluded that total reconstruction after the war may cost between $210-525 billion.

In light of that need, the Biden administration has already requested $8.5 billion in economic aid to Kyiv, along with $3 billion in economic relief. Furthermore, the EU has pledged to establish a trust fund to finance reconstruction in Ukraine and has already distributed $647 million in loans to the country. Meanwhile the IMF has approved $1.4 billion in emergency funding to Ukraine, and canceled $2.2 billion of Ukraine’s prior loan obligations under Ukraine’s pre-existing Stand-By Arrangement.

However, no matter what amount of aid is ultimately provided by the international community, such funding will be useless without strong oversight to avoid fraud, waste, and abuse. As argued by CSIS’s Cynthia Cook, the massive damage done by Russian attacks will require careful planning and investment to remedy, so a detailed recovery plan—such as was mandated for Puerto Rico after the 2017 hurricane—would be an excellent first step.

Furthermore, despite already planning to pay the bulk of Ukraine’s reconstruction costs, European leaders may eventually wish to shift some of the costs to Russia, specifically by seizing the assets of the Central Bank of Russia, sanctioned Russian banks, and the funds of sanctioned Russian oligarchs, as is advocated by the Peterson Institute for International Economics’ Gary Clyde Hufbauer and Jeffrey J. Schott, as well as former IMF chief economist Simon Johnson.

Above all, international donor governments should be aware that however much they end up providing to Ukraine in terms of reconstruction funds, there will need to be continued economic and rule-of-law reforms in Ukraine if donors do not want to see recovery funds siphoned off by crony capitalist friends of the Zelesnkyy administration. While it should be clear that allegations of the Zelenskyy government’s perfidy and corruption were somewhat exaggerated in the months leading up to the war, there are indications that more could have been done by the Zelesnkyy administration to accomplish long-awaited reforms. Therefore, in a reconstruction environment, where hundreds of billions in foreign funding may pour into Ukraine, oversight and accountability must be the watchword of all donor countries and civil society actors in Ukraine.

Closing Thoughts

Ultimately, the war in Ukraine is likely to drag on for at least the foreseeable future. Therefore, while it is unlikely that the U.S. or its European NATO allies decide to intervene in Ukraine via a no-fly zone or troop deployment, they will need to learn to better manage Putin’s escalatory tactics as the war continues to drag on. Furthermore, Western defense establishments need to use the shock of the war in Ukraine to transform their planning and readiness processes, as the war has demonstrated how unprepared Western states were to respond militarily to aggressive actions by a peer-competitor. Finally, the international community must be ready to rebuild Ukraine once the war is over, working with and through the Ukrainian government to complete needed economic and judicial reforms in order to effectively distribute reconstruction funds.

In the end, the invasion of Ukraine is a senseless act of aggression by Russian leadership which has seemingly backfired, as its forces have been unable to achieve the swift victory envisioned by Moscow. However, that does not mean that the operation is ultimately doomed to failure. To avoid defeat in Ukraine, and to keep the crisis from spiraling out of control, U.S. and European leaders will need to understand where and for what reasons Russia might escalate its attacks in Ukraine; be ready to better assess future threats from authoritarian states like Russia and China; work to rebuild the liberal international order at multilateral bodies such as the United Nations; and carefully work to rebuild Ukraine after the destruction caused by Russia.

As Ukrainian President Zelenskyy stated in his recent address to the US Congress on March 16, “Today, the Ukrainian people are defending not only Ukraine, we are fighting for the values of Europe and the world, sacrificing our lives in the name of the future. That’s why today the American people are helping not just Ukraine, but Europe and the world to give the planet the life to keep justice in history.” If they are able to accomplish all of the goals mentioned above, Western states might just provide Ukraine with the support it needs to defeat the Russian menace and secure a more peaceful future for its citizens.