August 5, 2022

Back on June 23, John Mearsheimer, the R. Wendell Harrison Distinguished Service Professor of Political Science at the University of Chicago, gave a speech at the European Union Institute, wherein he offered up an explanation for the war in Ukraine that repudiated Western governments supposed rationales for entering the war, placing the majority of the blame for the current catastrophe at the feet of the United States, the European Union, and the enlargement of the NATO Alliance. Mearsheimer’s contentions should not be surprising, as he has consistently stuck with the argument that Western military encroachment has been responsible for Russian aggression towards Ukraine since at least the 2014 Russian annexation of Crimea.

However, while Mearsheimer is clearly one of the foremost thinkers in international relations, his analysis is fundamentally faulty in both its examination of the historical record, as well as in his estimation that the war would end if the West simply agreed to abandon its partners in Kyiv. Furthermore, Mearsheimer is not the only “realist” foreign policy thinker who believes that Western military actions have largely been responsible for the outbreak of violence in Ukraine, with Mearsheimer’s frequent collaborator Stephen Walt also arguing that the U.S. largely provoked this year’s Russian aggression.

Therefore, it is worth taking some time to analyze Mearsheimer’s argument, as well as already existing rebuttals, to see exactly where he veers off course. To begin, Mearsheimer presents two essential arguments: that the U.S. is the actor that is principally responsible for the current crisis in Ukraine, and that the Biden administration has reacted to the war by doubling down on efforts to weaken Russia. However, it is not only difficult to argue that the U.S. or Western organizations are responsible for the war, it is hard to say that the Biden administration has specifically committed to “greatly weaken Russian power”. Mearsheimer argues that this is not to absolve the Kremlin of all responsibility for the war, merely to place the bulk of the blame on the West for creating a “security dilemma” for Russia, forcing its hand on Crimea, Donbas, and then, ultimately, all-out war with Kyiv.

Mearsheimer rejects Western arguments that Putin is motivated by “the historical unity of Russians and Ukrainians”, the feeling that the collapse of the Soviet Union, “was the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century,” or that, “modern Ukraine was entirely and fully created by Russia, more specifically the Bolshevik, communist Russia,” instead positing that Putin has long recognized the country as independent, pointing to the end of the Russian leaders July 2021 address, where he stated that, “Russia has never been and will never be ‘anti-Ukraine’. And what Ukraine will be – it is up to its citizens to decide”.

Mearsheimer says that those submitting that Putin was intent on conquering Ukraine and incorporating the country into Russia must first prove that Putin thought such a move desirable; feasible; and that he ultimately intended to pursue such a goal. As such, he argues that there is little evidence in the public record that would indicate that Putin was contemplating putting an end to the independence of Ukraine when he initiated his campaign in February. Further, Mearsheimer argues that Putin displayed little evidence that he thought that conquering all of Ukraine was feasible, pointing to Putin’s speech to the Russian people following the initiation of hostilities, that, “it is not our plan to occupy the Ukrainian territory. We do not intend to impose anything on anyone by force.”

Finally, Mearsheimer states that it can be clearly seen that Putin never intended to fully pursue a goal of conquering and incorporating large segments of Ukraine by virtue of the Russian military’s conduct in the early days of the war. Here, Mearsheimer contends that as Russia did not attempt a classic blitzkrieg strategy, aimed at overrunning the entirety of the country with armor and tactical air support, then it means that Russia always intended to pursue more limited aims in Ukraine. Moreover, he argues that there is no evidence that Russia was preparing a puppet government to replace the Zelenskyy administration, demonstrating again Russia’s more limited goals in the invasion. Additionally, Mearsheimer contends that, as Putin is a keen student of Russian—and particularly Soviet—history, he would understand as well as anyone that occupying large countries is a recipe for unceasing trouble and resistance to occupation. Finally, the author contends that it was only when the Maidan Revolution broke out in February 2014 that the U.S. subsequently began describing Putin as dangerous, allowing the West to place all the blame for the situation in the country on the Russian leader.

Mearsheimer maintains that the true root of the crisis has three prongs, which are: Western efforts to integrate Ukraine into the European Union; attempts to turn Ukraine into a pro-Western liberal democracy; and attempts to incorporate the country into the NATO Alliance. Mearsheimer ultimately traces the trouble between the West and Russia back to the Bucharest summit in April of 2008, when NATO members welcomed, “Ukraine’s and Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations for membership in NATO,” and, “agreed…that these countries will become members of NATO.” Mearsheimer contends that the West should have fully understood from the outset that such a move was a clear red-line for Moscow, with U.S. Ambassador to Russia William Burns writing in a memo to then-Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice that, “Ukrainian entry into NATO is the brightest of all red lines for the Russian elite (not just Putin). In more than two and a half years of conversations with key Russian players, from knuckle-draggers in the dark recesses of the Kremlin to Putin’s sharpest liberal critics, I have yet to find anyone who views Ukraine in NATO as anything other than a direct challenge to Russian interests.”

Despite this, Mearsheimer argues that the West, instead of recognizing Russian red-lines, plowed ahead with efforts to expand the NATO alliance, with the George W. Bush administration pressuring France and Germany to withdraw their objections to Ukraine and Georgia’s NATO accession path. Here, Mearsheimer claims that this American heedlessness led directly to the 2008 Russo-Georgian War; another inadvertent result of the West’s pursuit of integration with Russia’s former-Soviet partners.

Notwithstanding these facts, the author contends, the West learned no lessons, and instead recklessly pursued further integration efforts with Ukraine, with NATO and the U.S. conducting the training of the Ukrainian military, training tens of thousands of Ukrainian troops since 2014. Furthermore, Mearsheimer notes how in 2017, the Trump administration decided to provide Kyiv with lethal defensive arms, creating a permission structure for other NATO nations to do the same. Furthermore, Mearsheimer also points to Ukrainian participation in NATO exercises, with the massive Operation Sea Breeze in the Black Sea including the Ukrainian navy as well as navies from thirty-one other countries. Ultimately, all of these Western-Ukrainian partnerships undoubtedly caused consternation in Moscow.

In addition to military cooperation, Mearsheimer’s speech also contends that, in 2021, Western rhetoric surrounding Ukraine’s potential integration into NATO changed, as Zelenskyy began to embrace the idea of NATO accession and adopt a more hardline approach towards Russia. This renewed commitment to Ukraine’s Euro-Atlantic integration led NATO to issue, in June of 2021, a communiqué following its annual Brussels summit reiterating the 2008 Bucharest declaration that Ukraine will have a path towards NATO accession. In addition, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba proceeded to sign the U.S.-Ukraine Charter on Strategic Partnership in November of that year, further underscoring Ukraine’s commitment to the reforms required for its full integration into Western institutions.

As such, Mearsheimer contends that the West should not be surprised by Russian hostility towards these moves, as Moscow sent letters to both the Biden administration and NATO demanding written guarantees that Ukraine would not join the alliance; that no offensive weapons be placed on or near Russia’s borders; and that NATO troops and equipment moved into Eastern Europe since the 1997 NATO expansion be removed. At the time, Putin argued that, “what [NATO is] doing, or trying or planning to do in Ukraine, is not happening thousands of kilometers away from our national border. It is on the doorstep of our house. They must understand that we simply have nowhere further to retreat to.”

For Mearsheimer, despite all of these public indications and statements from Moscow that Western integration of Ukraine is clearly an unacceptable course of events, the U.S. and its Western partners plowed ahead, oblivious to the imminent dangers inherent in their course of action. He therefore argues that the West must face the predictable consequences of its actions in Ukraine and work to both prevent nuclear escalation as well as find a way out of the entire mess. For Mearsheimer, the key to such a settlement is rendering Ukraine a neutral state after the war, ending its prospects of further NATO and EU integration. However, he blames both radical nationalists inside the country as well as the Biden administration—which he argues has committed to the decisive defeat of Russia in Ukraine—for the inability to dial down temperatures and discuss potential diplomatic solutions to the war. Finally, he states that there is little to suggest that President Zelenskyy will accept any deal that allows Russia to keep any Ukrainian territory, which would be a clear dealbreaker for Moscow.

Mearsheimer proceeds to outline all the ways that the war is a catastrophe for Ukraine and the globe, from destroyed Ukrainian critical infrastructure; to massive internal and external displacement; and a growing global food and energy crisis. Furthermore, with a strong Western rhetorical commitment to defeating Russia—and a similar commitment to victory posited to exist in Moscow and Kyiv—a settlement between the sides that is acceptable to all is remarkably unlikely with Ukraine and Russia viewing defeat as an existential threat to their way of life. In that light, Mearsheimer argues, there is a very real danger of escalation, even to the use of nuclear weapons, as Moscow will not sit idly by as the U.S., “wants to see Russia weakened to the degree that it can’t do the kinds of things that it has done in invading Ukraine,” as was stated to reporters by U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin back in late April. With both sides unable to claim a victory without the others’ defeat, Mearsheimer contends, it leads to a situation where Russia could decide to use nuclear weapons, as was argued by U.S. Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines back in May.

In the end, Mearsheimer submits that the 2008 Bucharest summit declaration’s commitment to draw Ukraine and Georgia into the Western orbit was ultimately destined to result in conflict with a Russian leadership which views NATO encroachment as anathema. He argues that while the Bush administration was the architect of the 2008 decision to commit to Georgia and Ukraine, that it was decisions by the Obama, Trump, and Biden administrations that have exacerbated that initial, faulty—in Mearsheimer’s estimation—choice. He contends that had the West simply not pursued NATO expansion into Ukraine, that it is likely Russia would have undertaken none of its military incursions against its neighbor, and that Crimea would still be a part of Ukraine. Ultimately, he states that history will judge the West harshly for its foolhardy pursuit of Ukrainian integration into Euro-Atlantic structures, as that is the ultimate factor resulting in the death and destruction currently taking place.

What’s Missing from Mearsheimer’s Analysis

Mearsheimer’s argument is compelling; and, if taken as submitted, would seem to offer a succinct and logical explanation for the events that have played out over the last eight years. Unfortunately, however, his argument ultimately does not address the full range of facts surrounding Russian rhetoric and decisions over the past two decades. As Joe Cirincione of the Council on Foreign Relations wrote in a July 29 article for the Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, the most important gaps in Mearsheimer’s analysis are, “the security imperatives of Russia’s neighbors, the increasing authoritarianism of the Russian state and the true horror of Russia’s brutal war and occupation.” Cirincione argues that, “by not adequately weighing these factors, Mearsheimer can explain Putin’s invasion of a peaceful, independent nation as a predictable reaction to Western provocations.” As such, it is worth analyzing Cirincione’s arguments in greater detail.

To begin—while acknowledging that NATO enlargement was problematic and that the U.S. did not do well to take Russian security concerns into account—Cirincione states that NATO policy was not driven by some obsession with making Ukraine a bulwark against Russia, but rather a simple extension of bureaucratic inertia and the pursuit of profitable defense contracts for Western defense companies. Furthermore, he notes that even if NATO’s enlargement was in response to Russia, it was a response to the historical actions of the Soviet Union, rather than the immediate, post-Cold War Russia that was struggling to hold its economy together—specifically as former-Soviet states of the Visegrád group had good historical reason to fear their larger, more powerful neighbor and pursue NATO accession. As such, Eastern Europe’s desire for NATO integration was less about Western domination of Eastern Europe than about what the publics in Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Poland desired for their future political and economic orientation.

Cirincione also disputes Mearsheimer’s assertion that Putin has only pursued limited aims in Ukraine, noting that Russian efforts failed not because of some careful calibration by Moscow but the heroic resistance of Ukrainian soldiers. Cirincione backs up his argument with a statement by Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, who said in late July that Moscow is, “determined to help the people of eastern Ukraine to liberate themselves from the burden of this absolutely unacceptable regime,” stating that, “[Russia] will certainly help the Ukrainian people to get rid of the regime, which is absolutely anti-people and anti-historical.”

Furthermore, Cirincione points to a recent Putin speech from June, where he does not mention NATO enlargement, but instead waxed rhapsodic about the wars of Peter the Great, which—he argues in a strikingly similar way to now the war in Ukraine is described—restored rightful Russian territory to the country’s people. Moreover, Cirincione points to Russian efforts to ‘Russify’ areas under its control, introducing rubles as the new currency, handing out Russian passports, and attempting to re-educate teachers and children with pro-Russian dogma. Cirincione argues that as Putin has long feared a wave of popular resistance emerging in Russia that poses a threat to his regime, he has thus attempted to control both the people and the narratives in Ukraine in order to tamp down on Western sentiment both inside and outside his own country. Cirincione points to former U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine, Steven Pifer, who wrote in late July that, “for the Kremlin, a democratic, Western-oriented, economically successful Ukraine poses a nightmare, because that Ukraine would cause Russians to question why they cannot have the same political voice and democratic rights that Ukrainians do.”

For Cirincione, Putin’s invasion is not about the struggle between Putin and the West, but between Putin and his own people, as his growing authoritarianism and personalist dictatorship mean that he must crack down on alternatives to his rule lest ordinary Russians decide that there is a need for regime change.

Finally, Cirincione states that the most critical flaw in Mearsheimer’s analysis is his minimization of Russian atrocities since the war broke out. From the military massacre at Bucha to the seizure of Ukrainian children for adoption back in Russia, the way Russia has prosecuted its war in Ukraine has been downright horrific. For Cirincione, this is not the actions of a state intent on pursuing “limited aims” in Ukraine, but the prosecution of a “sustained war of destruction” which has scorched the earth, kidnapped local elites, raped women and girls, and murdered any men believed capable of military activity.

With Mearsheimer missing these key elements in his analysis, Cirincione argues, he ultimately arrives at the flawed conclusion that it is on the West to do what it can to seek an end to the war, pressuring Kyiv to turn over up to a quarter of Ukraine’s territory over to Russia, including the millions of Ukrainian citizens living there. However, in Cirincione’s estimation, such a surrender would not end all Russian aggression, merely temporarily satiate the beast, and lead the country to continue its offensive after a pause to absorb the lands it occupies and resupply its armed forces.

More Missing Pieces

However, as excellent as Cirincione’s analysis is, even that is missing some other elements that shine a light on the behavior of Vladimir Putin towards Ukraine. To begin, Mearsheimer’s analysis states that the West’s original sin in Ukraine was the 2008 Bucharest summit declaration which paved the way for future hostility between Russia and the West. However, while that may be a convenient starting point for making the argument that Russian fears are largely driven by Western provocations, it misses the fact that Russia has long had an international legal commitment to the independence and territorial integrity of Ukraine, dating back to a promise made fourteen years earlier and around five hundred miles away in Budapest.

The 1994 Budapest Memorandum on security assurances in connection with Ukraine’s accession to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, signed between Ukraine, the Russian Federation, the United Kingdom, and the U.S., provided, in its second clause, that, “the Russian Federation, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and the United States of America reaffirm their obligation to refrain from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence [emphasis added] of Ukraine, and that none of their weapons will ever be used against Ukraine except in self-defense or otherwise in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations.” Despite this binding commitment, already, four years before the contentious 2008 Bucharest declaration, the Russian president was deeply involved in violating the political independence of Ukraine, with alleged efforts to poison the Western-leaning Viktor Yushchenko—a traditional method of choice for the Russian security services—as well as more directly wading into the particulars of the 2004 runoff election in that country.

This involvement by Putin likely emerged, as has been argued by former U.S. ambassador to Russia, Michael McFaul, out of a fear, “that the United States was orchestrating [Arab Spring] revolutions, just as he believed it had in Serbia in 2000, Georgia in 2003, and Ukraine in 2004.” Specifically, as McFaul remarked on Twitter back in late March of this year, “Putin has been paranoid about the US [being] out to overthrow his dictatorship for a long long time.” While Putin may point to U.S. involvement in the Orange Revolution in Ukraine as evidence of Western “meddling”, the U.S. did not directly fund the Yushchenko campaign and Western funding merely supported the holding of free and fair elections. While President Putin may find the holding of such elections to be unfair to his autocratic worldview, it would be exceedingly tendentious to say that the U.S. violated the political independence of Ukraine in the same way that attempting to poison a pro-Western candidate for office did.

Indeed, it is hard to examine the history and not come to the conclusion that as soon as the people of eastern Europe began to throw off the shackles of autocrats that Putin began to feel nervous not only about his position in Russia, but about “Western encroachment.” More specifically, it is Putin’s particular worldview—shaped by the events shortly before, during, and after his election to the Russian presidency—that perhaps best explains that downturn in relations over the last two decades.

Despite Russian displeasure at what it saw as an illegal NATO intervention in Yugoslavia to stop the war crimes of the Milošević regime—an intervention prompted as much by the Clinton administration’s guilt at having done not enough to prevent a genocide in Rwanda as by NATO’s newfound commitment to a more muscular foreign policy—the Western intervention in 1999 was initiated in the indisputable context of stopping the ethnic cleansing campaign going on there.

As Cornell School of Law professor David Wippman wrote for the Fordham International Law Journal in 2001, “any judgment regarding the success or desirability of NATO’s intervention in Kosovo necessarily rests on unprovable assumptions. We can only speculate on what would have happened had NATO refrained from intervening. It seems probable, though, that the violence in Kosovo would have escalated, with potentially grave repercussions for the entire region…” and that, “on balance, then, it seems likely that both Kosovo and the region are better off than they would have been…” Finally, Wippman writes that, “unfortunately, NATO’s objectives could only be pursued by circumventing the U.N. Charter’s framework for the use of force…”

Despite Russian protestations regarding NATO involvement in Kosovo, Putin did not contemporaneously indicate that it spelled a death knell for relations between Russia and the West. In fact, during a March 2000 conversation with legendary British television presenter David Frost, when asked whether it was possible that Russia could join the NATO Alliance, the soon-to-be Russian President replied that, “I don’t see why not. I would not rule out such a possibility,” and that, “when we talk about our opposition to NATO’s eastward expansion, we do not have in mind our special ambitions with respect to some or other regions of the world. Mind you, we have never declared any region of the world a zone of our special interests.” More importantly, shortly after the 9/11 attacks, Putin declared his openness to reconsider Russia’s past opposition to NATO expansion into the former Soviet states of eastern Europe, saying that, “As for NATO expansion, one can take an entirely new look at this… if NATO takes on a different shade and is becoming a political organisation.”

Moreover, Russian concerns about Western involvement on its periphery seem to be not as much about NATO encroachment as it is about Putin’s view that Russian sovereignty means the ability to violate the sovereignty of its neighbors when pursuing its own “security interests.” Specifically, since the early days of Putin’s rule, he has—just like fellow autocrat Xi Jinping—viewed the world through the lens of the breakup of the former Soviet Union and the dissolution of what constituted the Russian Empire. As was noted in a 2002 piece from The New York Times, “Mr. Putin’s bleak memories of the successive collapses of East Germany, the Soviet Union, and the K.G.B. he long served have left him deeply committed to preventing any further disintegration of Russia.” It is here that Putin’s paranoia about bandits and terrorists began to be on display in full force, with Putin acquaintance Alexander Rahr stating that Putin is, “obsessed with Chechnya. He has been from the beginning.”

However, despite the brutality of the Russian campaign in Chechnya, the incoming Bush administration, “advocated a greater focus on the great powers in the world, such as Russia and China, and less attention to ‘humanitarian concerns’ such as Haiti, Somalia, Bosnia, and Kosovo,” as was noted in a 2003 paper by Michael McFaul. Further toeing the Russian line, “Bush administration officials had repeatedly stressed that the issue of Chechnya was covered at length behind closed doors,” but that, “when Bush has alluded to the Chechen situation publicly, however, he and the senior officials in his government have often adopted Putin’s portrayal of the Russian military operation as part of the war on terrorism.”

It is also inescapable that around this time, Putin began to assert more autocratic control over the Russian nation. As Eric Chenoweth and Irena Lasota wrote in a March 18 article for the Reiss Center on Law and Security at New York University School of Law’s blog, Just Security, “Putin’s assumption to power, however, was not just as an individual. He was the chosen representative of an anti-democratic, post-communist system built around the reconstituted ‘organs of power,’ namely the security, intelligence, and military agencies. Trained in ‘late Stalinism’ during the periods of Leonid Brezhnev and Yuri Andropov, the scions of this new system aimed to restore Russian ‘greatness’ and dominion over a former empire,” and that, “Putin’s first tasks were to destroy democratic features that emerged within Russia since 1991 and all manifestations of independence among the remaining nationalities directly under control of the Russian Federation, most significantly the Chechen Republic.”

Furthermore, as Michael McFaul stated in an October 2021 article for the Journal of Democracy, in the first five years of his presidency, “Putin did, however, immediately reign in autonomous political institutions, organizations, and individuals that could constrain presidential power. He first seized control over national television networks, understanding that these assets played an essential role in delivering electoral success in the 1999 parliamentary election and his presidential election in 2000.” McFaul continues that, “in these early years, Russian democracy eroded significantly,” as, “scholars considered the political system a dictatorship, albeit with softening adjectives such as ‘electoral,’ ‘competitive,’ ‘unconsolidated,’ or ‘hybrid.”

It is therefore striking that overt Russian aggression towards its neighbors did not begin until 2008, when, according to McFaul, “Putin felt so in control that he stepped down as president, allowed his loyal aide, Dmitri Medvedev, to assume that office, and took over as prime minister himself.” Furthermore, in 2008, “[the] global financial crisis ended years of economic growth and weakened support for the government.” In that light, one can see how Putin’s aggressive posture towards his neighbors can be seen as more about his own domestic political situation than anything regarding NATO actions during that time period.

As was argued by the Wilson Center’s Stephan Kieninger in a June 2022 commentary, “When Russia annexed Crimea and started its war in eastern Ukraine in 2014, Putin emphasized the reputed humiliation Russia had suffered in the face of broken promises by the West, including the alleged promise not to enlarge NATO beyond the borders of a reunited Germany. For more than twenty years, the “broken promise” has been a foundational leitmotif of Russia’s post-Soviet identity.” However, in reality, Kieninger states that, “there is no truth to it. In the 1990s the Bush and Clinton administrations engaged Russia on a broad scale. America used its “unipolar moment” as a chance to facilitate Russia’s transformation and its integration in the global community of nations.”

Furthermore, there is a strong argument to be made that Putin, during his early years in power—and despite the early, warm relations with the Bush administration—was already interfering in the internal affairs of his neighbors, specifically through the weaponization of Russia’s 2002 “Federal Law on Citizenship of the Russian Federation,” which enabled people who once had Soviet citizenship, or those that reside in states that formed part of the Soviet Union, to obtain Russian citizenship.

As explained by Elia Bescotti, Fabian Brukhardt, Maryna Rabinovich, and Cindy Wittke in a March 25 piece for the European University Institute’s Global Citizenship Observatory, “by obtaining a Russian passport, these people became Russian citizens and ‘compatriots’ who had to be protected by the Russian Federation according to Art. 15 of the 1999 Federal law ‘On the state policy of the Russian Federation in the relations with compatriots overseas’ and Art.7 of the Law on Citizenship,” and that, “since 2002, Russia started its passportization policy and intensified it in the contested regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia after the 2003 Rose Revolution in Georgia,” resulting in, “90% of the population of Abkhazia and South Ossetia,” holding Russian passports by 2006.

Just as Putin rails that the West has used NATO expansion as an excuse to encroach on Russian interests in eastern Europe, Russia has similarly used “passportization” as a somewhat flimsy legal pretext to interfere in the sovereignty of its neighbors. As the Global Citizenship Observatory piece notes, “when Georgia undertook military action against South Ossetia’s provocations in August 2008, Russia reacted with a disproportionate military response against Georgia,” stating that, “Russia justified its military actions with Art. 51 of the UN Charter and its responsibility to protect Russian nationals in Abkhazia and South Ossetia from a Georgian “genocide.” Ultimately, Russia, “then recognised the two contested states as independent states on August 26, 2008,” despite Russia’s interpretation of the legality of those contested states’ remedial secession being unsupported by common practice in international law, nor backed by the EU’s International Independent Fact-Finding Mission on the Conflict in Georgia, which, “rejected the Russian argument for intervention in a situation that Russia had engineered itself.” In sum, while Putin views Western rhetoric surrounding democracy promotion as a thin pretext for those states’ interference in eastern Europe, Putin has similarly used a rather transparent cloak to hide his own interference in the affairs of his neighbors in the pursuit of increased Russian influence in those states’ affairs.

A Particularly Putin-shaped Problem

Ultimately, a better way to view the actions of Vladimir Putin since he took the reins in Moscow in 2000 is through Putin’s quest to crush separatism, first in Chechnya, but later in the countries of the former Soviet Union, land which Putin saw a part of Russia’s “privileged sphere of influence.” Moreover, in analyzing the path of the relationship, one can see how an initially positive U.S.-Russian relations under the George W. Bush administration—forged in the immediate aftermath of the 9/11 attacks and the “global war on terror”—would later sour and then turn even worse under the more human-rights-focused Obama administration.

As Dmitri Trenin wrote in a 2003 policy brief for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, in the Kremlin’s view, “it took the 9/11 disaster for the United States to see the danger of terrorism,” and that by immediately declaring his solidarity with the U.S. following the attacks, Putin, “managed to subsume the war in Chechnya within the global fight against terror…Moscow was not joining Washington’s war on terror, but exactly the other way around.” As long as the Bush administration was willing to look the other way while Putin continued his brutal campaign in Chechnya, the Russian leader was more than willing to maintain a friendly relationship with the U.S. as long as he was getting what he wanted.

Indeed, as Michael McFaul writes in his book, From Cold War to Hot Peace, “in November 2002, NATO invited Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia to join the alliance; two years later, these states became NATO members. At the time, Putin called NATO obsolete and ridiculed the security gains of expansion. However, it would be only, “years later [that], Putin would resuscitate NATO expansion as a major issue of contention in Russian-American relations.” As McFaul concludes, “U.S.-Russia relations were strained but not broken by this latest wave of NATO expansion.”

However, the relationship with the Bush administration would take a turn for the worse over U.S. involvement in Iraq, with “Russian Foreign Minister Igor Ivanonv [criticizing] the Bush administration almost daily since the war in Iraq began,” as noted in a 2003 report from The Washington Post. There is also other evidence that the relationship between the U.S. and Putin was taking a turn for the worse even before the 2008 Bucharest declaration, with the Council on Foreign Relations’ Stephen Sestanovich saying in 2007 that the U.S.-Russia partnership is, “ a chilly kind of unproductive relationship,” as the Bush administration became frustrated with Russian opposition on Iran, Darfur, and Kosovo.

It was only after relations began to sour with the Bush administration, and then really turned for the worse under the Obama administration, that Putin renewed his objections to NATO’s continued enlargement. In essence, he was largely fine with the expansion of the Alliance as long as the U.S. was largely allowing him to have his way in Russia’s near-abroad; things only took a turn for the worse once the U.S. began to criticize and constrain his behavior.

As was noted in a September 2018 report from the Center for American Progress, “between 1970 and 2010, the number of democratic states nearly tripled,” so that, “by 2000, more than half the world’s population lived under a democratic government for the first time in recorded history. This democratic wave brought a host of political and social rights to hundreds of millions of people and coincided with a historic decline in the incidence of interstate wars.” As such, “America’s enduring security, prosperity, and strength depend on the survival and success of democracy—both at home and abroad—as well as on the resilience of institutions, rules, and norms that protect the liberal democratic values on which the United States’ global standing is built.” Ultimately, therefore while NATO expansion is a convenient bogeyman for the Kremlin, it ignores the central fact that the U.S. relationship with Russia under Vladimir Putin was never going to be anything but contentious as long as the U.S. and its allies remained staunch supporters of democratic movements around the world.

As Michael McFaul notes in his book, From Cold War to Hot Peace, beginning in 2000, “Putin was moving Russia in an autocratic direction. To strengthen the state, Putin believed that he had to weaken checks on his power.” McFaul further warned in a March 2000 Washington Post op-ed that, “if a new nationalist dictatorship eventually consolidates in Russia, [the U.S.] will go back to spending trillions on defense to deter a rogue state with thousands of nuclear weapons.” In light of that, it is much easier to view Putin’s infamous 2007 Munich Security Conference speech that railed against NATO enlargement being less about the provocations posed by the Alliance’s expanding military footprint as it was about the further entrenchment of solidly democratic states on Russia’s border.

Ultimately, the U.S. was never likely to abandon its pursuit of democratization in eastern Europe, as the main benefit of that pursuit—which were so eloquently put in a 2013 statement of principles co-issued by the Center for American Progress (CAP)and the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS)—is the fact that, “a freer and more democratic world helps create a virtuous circle of improved security, stronger economic growth, and durable alliances—all of which better serve the long-term interests of the United States,” and that, “accountable, effective, and democratic governments make better and more reliable trading partners and provide the cornerstones of international stability.” Finally, the joint CAP/CSIS paper concludes that, “given their modest scale and numerous benefits, America’s official investments in promoting democracy and governance abroad deserve to be sustained even as we deal with very real budget challenges in this current era of fiscal austerity.”

Despite the fact that, “from the end of the Cold War until Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in 2014, NATO in Europe was drawing down resources and forces, not building up. Even while expanding membership, NATO’s military capacity in Europe was much greater in the 1990s than in the 2000s,” during that same period, “Putin was spending significant resources to modernize and expand Russia’s conventional forces deployed in Europe,” even as” the balance of power between NATO and Russia was shifting in favor of Moscow.”

In essence, even while the NATO military threat to Russia was declining, Putin saw it as increasing almost entirely due to his own autocratic consolidation of power at home and abroad. As he cracked down on democracy at home, he became even more unable to allow pro-Western democratic movements to flourish in Russia’s near-abroad out of a fear that such movements could spread into Russia and eventually topple his regime. In that light, the Russian “security dilemma” was, in fact, of Putin’s own making: in attempting to maximize his own regime’s security by undermining democratic movements at home and abroad, he paradoxically created the conditions for Russia’s own insecurity, especially as, “in Ukraine, Russia’s meddling in the 2004 presidential contest helped spawn protests against corruption and for fair elections,” and, “in another round of protests a decade later, Ukrainians overthrew a pro-Russian government and replaced it with one closer to Europe and the West.”

Mearsheimer’s essay seemingly makes the case that in Ukraine, the West must reckon with the results of its provocations towards Russia during the past two decades. However, it is the Russian leaders’ own actions that have created the conditions for today’s war, not Western Alliance expansion—though that was, undeniably, a useful scapegoat for Putin, domestically.

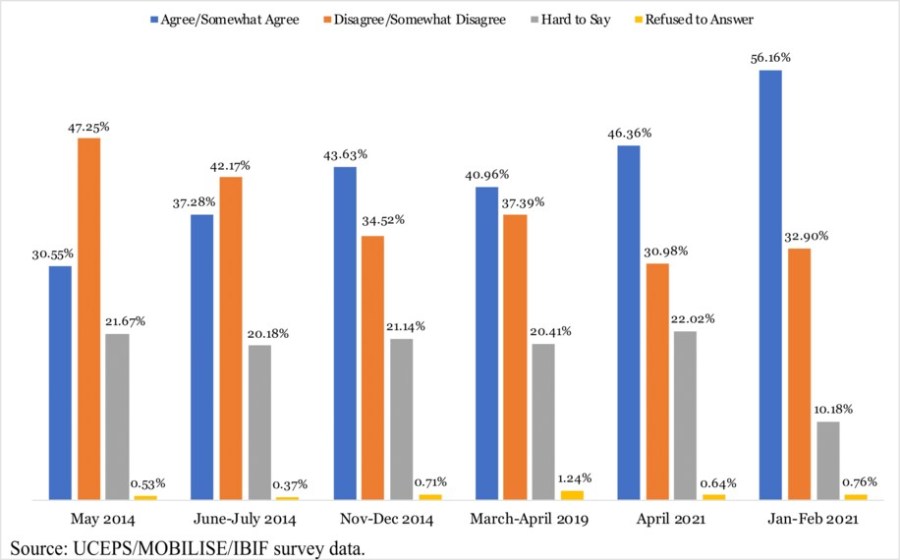

From the beginning, Putin’s actual fears were less about NATO encroachment and more about democratic encroachment on Russia’s periphery. As far back as 2004, Putin began to fear that, “some US allies seemed intent on ‘isolating’ Russia and eroding its power in its traditional sphere of influence.” Therefore, while NATO expansion did likely play a part in Putin’s calculus, it was, according to Natia Seskuria of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, “the gradual success of the democratization process,” which, “caused major dissatisfaction in the Kremlin and eventually led to its use of military force,” against Georgia in 2008. Furthermore, the, “overt Russian aggression [in Georgia] has hurt the Kremlin’s long-term strategic goals,” as, “since 2008, popular support for Georgia’s European and Euro-Atlantic integration has risen to an all-time high.” Similarly, the Russian aggression towards Ukraine since 2014 has shifted Ukrainian public opinion on the country’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations.

In the end, while NATO enlargement was a convenient excuse for Putin’s paranoia, it was largely democratic movements in the countries of the former Soviet Union—and the U.S. and European support thereof—that ultimately led Putin to pursue a strategy of aggression towards his neighbors. In trying to stifle the nascent Euro-Atlantic desires of Georgia and Ukraine, Vladimir Putin sowed the winds of his current troubles; now, in Ukraine, he must reap the whirlwind.