August 12, 2022

As Ian Bond and Luigi Scazzieri of the Centre for European Reform have recently written, “Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in February has established a new political and military reality in Europe. The threat of repeated Russian military action is now more severe, and the EU and NATO will have to reorient themselves towards deterring further aggression, while overcoming old rivalries and mutual suspicions.” Furthermore, they note that it would be a mistake for EU countries to believe that the U.S. will continue to step up and bear the majority of costs, as Europeans, “will have to do more, acting nationally, in small groups and through the EU and NATO.” Ultimately, Bond and Scazzieri conclude that Putin’s war has demonstrated how, “Europe can no longer afford to treat its own security as a matter of little consequence.”

The ongoing conflict in Ukraine has further demonstrated to Western nations that, “Russia has expansionist ambitions that stretch across much of eastern Europe,” and that, “Putin’s ambitions to reconquer significant parts of the Russian empire means that Russia will continue to pose a threat to European security so long as it is ruled by him, or by someone else with the same aggressive imperialist mindset.” As Bond and Scazzieri write in “The EU, NATO and European security in a time of war,” despite a renewed focus on Russia, “other threats to European security have not disappeared,” and with trouble brewing in the Western Balkans, the “near uninterrupted expansion in militant Islamist violence” taking place in the Sahel, and growing competition with China in its own neighborhood, the European Union will, in the coming years, need to take on a greater role, “in security and defense, particularly in terms of capability development.”

However, while a renewed focus on European security has seen EU members Finland and Sweden apply for NATO membership, Germany undergo a historic geopolitical shift, and many European capitals decide to finally raise their ambitions for their levels of defense spending, none of it changes the fact that, as Sebastian Clapp of the European Parliamentary Research Services wrote in May of this year, that, “while defence budgets have increased in real terms since 2018/2019 (prior to that, they had not even reached pre2008 financial crisis levels), this follows years of chronic under-investment in defence in the majority of Member States.” Furthermore, Clapp notes that in the interim, “strategic competitors such as Russia and China have increased their defence budgets by almost 300% and nearly 600% respectively over the last decade, compared to an approximate 20% increase collectively by EU Member States in the same period.”

As such, back on March 11, at an informal meeting of the Heads of State or Government, the EU issued its “Versailles Declaration” which, responding to Russia’s hostilities in Ukraine, called for bolstering EU defense capabilities, reducing its energy dependence on Russia, and building a more robust economic base. While reducing European energy dependence on Russia and building a more robust economic base are both of long-term import to the European Union and its member states, a more tricky problem will be bolstering the EU’s defensive capabilities while still retaining the funds to complete Europe’s green transition and combating the disastrous economic effects of the war.

As such, when considering how it can bolster its defenses, the European Union must consider more “out of the box” thinking that allows member states to increase their defensive capabilities while doing so at a reasonable cost. Therefore, one of the strategies that EU member states must consider is defense specialization; and one of the main tools that it should use to achieve that strategy is through multinational defense cooperation. Moreover, they must do so because the past decade-and-a-half worth of collaborative efforts have, so far, failed to yield the desired results.

A Past Failure to Collaborate

In general, the conversation surrounding specialization in European defense is primarily about overcoming a legacy of confusing terminology as well as a historic hesitancy to truly rely on other countries for key parts of national defense. However, one merely has to look at the alternative to discover why EU nations have little choice but to embrace specialization or be unable to meet the challenge posed by a revanchist Russia under Vladimir Putin.

As was pointed out in the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ (CSIS) November 2021 report, “Europe’s High-End Military Challenges The Future of European Capabilities and Missions,” by Seth G. Jones, Rachel Ellehuus, and Colin Wall, “over the last decade, the state of allied military capabilities has improved in both qualitative and quantitative terms, including by meeting NATO Capability Targets, filling key capability shortfalls, and reducing dependence on the United States. Yet, overall, the picture is mixed, with some allies stepping up more than others and some targets still not met.” Moreover, the readiness picture becomes even more muddled when one considers that, “even when European NATO allies possess the required number of forces, they are often challenged by the lack of readiness in these large-scale combat formations,” with many units, “…hollowed out, inadequately trained, not yet modernized, or lack[ing] the necessary enablers to execute high end operations.”

Ultimately, Jones, Ellehuus, and Wall conclude that, “for the most demanding scenario, namely large-scale combat against an adversary such as Russia, the picture is challenging even with U.S. involvement due to the close, contested nature of the operating environment. To this end, it will be important for European allies to increase their readiness and field capabilities essential to improving situational awareness, force protection, and neutralization of enemy defense.” For the CSIS authors, while EU nations may have the capability to conduct crisis response and security cooperation missions in Europe and the surrounding neighborhood, when it comes to large-scale combat—especially against Russia—European militaries may very well not be up to the task, at least as currently constructed.

If Europeans are going to be realistic about their prospects of bridging these capability gaps, and meeting the challenge posed by Russia, decision makers are going to have to be honest about not only their existing equipment shortfalls, but about their overall commitment to higher levels of defense spending. As currently constituted, European defense spending is not even meeting the goals that member states had previously committed to.

As has been remarked on by Daniel Fiott of the Centre for Security, Diplomacy and Strategy in a June 2022 piece for Intereconomics, while, “the European Defence Agency estimates that EU members invested €198 billion in defence in 2020,” it was, “only after they collectively cut spending from 2008 to 2014 by €24 billion in the wake of the 2007 financial crash.” Furthermore, Fiott notes, even with states like Germany voicing a commitment to increase its level of defense investment, “some of the investment will be needed to cover essential capability gaps,” so, “in this respect, we should not expect these national funds to be exclusively invested in European collaborative solutions.”

However, as noted by Dick Zandee in a 2020 report, “The CSDP in 2020: The EU’s legacy and ambition in security and defence,” while, “the further Europeanisation of development and procurement of military equipment will certainly contribute to the rationalisation and consolidation of industrial capacities and to improving military interoperability and standardisation,” if, “Europe opts for a business-as-usual approach – long bureaucratic processes for the harmonisation of requirements; carving up technological research, industrial development and production shares based on the principle of juste retour; adding national ‘nice to haves’ to multinationally agreed ‘needs to have’ – then we can expect a repetition of the very expensive and slowly progressing collaborative armament projects of the past.”

Moreover, Zandee points out that while the EU’s European Defence Fund carries a requirement that at least three EU member states and three different companies participate in a project in order to receive EU funding, the selection of collaborative programs has been hindered by the European Commission, which, “in its communications about the EDF is mainly underlining the purpose of the EDF in strengthening the [EU’s Defence Technological and Industrial Base] rather than selecting programmes based on the capability priorities stemming from the [Capability Development Program] and the [Strategic Context Cases].”

As a result, over the last two decades, there has been an increasing awareness that the EU has had major capability shortfalls while, “the practice of capability development has only partially followed its theory,” as “defence bureaucracies did not follow up on what their political masters had decided in the past.” For instance, “in 2005 the first EU High Representative and Head of the EDA, Javier Solana, launched a campaign for a serious increase in collaborative defence [research and technology] spending with the motto ‘to spend more, to spend better and to spend more together.” And while he initially obtained European Council support for his plan, ultimately, “Solana’s initiative received no serious follow-up from the R&T experts in capitals.” As such, when the 2008 financial crisis hit, “collaborative European Defence R&T spending dropped from its peak of 16.6% (in 2008) to 8% (in 2017) – well below the benchmark of 20% agreed by ministers of defence in 2007.”

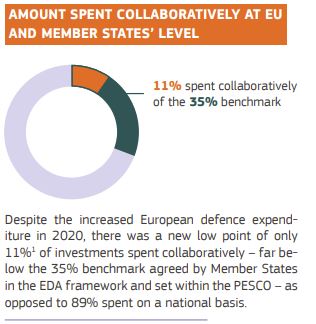

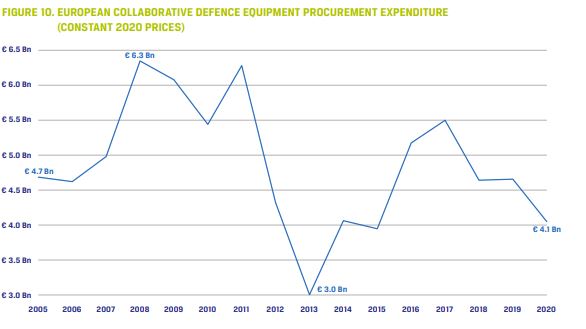

Further illustrating Europe’s collective inability to spend collaboratively on defense, in November 2007, the European Defence Agency’s (EDA) Ministerial Steering Board agreed to the creation of four voluntary benchmarks for defense investment, including a commitment by member states to try to spend 35% of total equipment spending on collaborative equipment procurement. However, a 2021 report by the EDA, “Defence Data 2019-2020: Key findings and analysis,” showed that, despite this decade-long commitment, EU member states, “fall collectively short of achieving the benchmark of spending 35% of their total defence equipment procurement in cooperation with other EU [member states], which is also a commitment under PESCO.” Furthermore, the report notes that while, in 2020, EU member states only, “conducted 11% of their total equipment procurement in a European framework,” the more egregious failure is the fact that, “since 2016, the share allocated to European collaborative equipment procurement has been decreasing continuously, reaching a new lowest level in 2020.”

Ultimately, European states have shown that they are either unwilling or unable to meet collaborative spending goals, and, as a result, European capability development has lagged behind where it needs to be to meet the challenge posed by Russia. As the authors EDA’s 2021 Defence Data report remark, “the defragmentation of the European defence capability landscape can only be achieved through a parallel increase in European cooperation, helping [member states] to procure their military equipment more efficiently.”

Therefore, with the historic reluctance shown by many EU member states in actually meeting their professed financial commitments to collaborative defense projects, something must change moving forward. Taking these factors into consideration, EU member states must more strongly consider concentrating on their existing areas of expertise and relying more closely on fellow member states for key elements of their collective defense if they want to keep spending levels down and readiness levels high.

To Specialize or Not?

As Dick Zandee and Adája Stoetman of Clingendael – the Netherlands Institute of International Relations (Clingendael) write in their July 2022 report, “Specialising in European defence: To choose or not to choose?”, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has made it clear to both NATO and the EU that their European member states must do more to bolster their defensive capabilities. However, recognizing that, “the rising costs of armaments, in particular high-technology weapon systems,” creates a system of “haves” and “non-haves” in Europe, the authors propose that, “multinational defence cooperation is the tool to prevent,” countries from seeking national solutions to European capability shortfalls and, as such, “defence specialisation should become an important element in strengthening European military capabilities.”

However, the conventional wisdom regarding European defense institutions typically is similar to that offered by former U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, who once stated that there were European nations jeopardizing the NATO alliance due to their aversion to, “shar[ing] the risks and costs” of defense investments. Despite this, as was argued by Kaija E. Schilde, Stephanie B. Anderson and Andrew D. Garner in their 2019 paper, “A more martial Europe? Public opinion, permissive consensus, and EU defence policy,” public opinion polling data in Europe has shown high levels of support for both national as well as European defense institutions, and that, “pooling national sovereignty over defence is more popular over time than any other EU-level policy.” In that light, it is worth considering what Zandee and Stoetman mean when they refer to defense specialization, what the barriers might be, and what potential benefits it might bring to European defense.

In the EU’s 2022 Strategic Compass, the report remarks that, “a number of Member States have embarked on the development of key strategic capability projects, such as next generation aircraft systems, a Eurodrone, a new class of a European naval vessel and a main ground combat system,” all of which will make tangible impacts on European security and defense. However, in that same section, the report also notes that, “in addition to investing in future capabilities and innovation, we need to make better use of collaborative capability development and pooling endeavours, including by exploring tasks of specialisation between Member States,” building on successes such as the European Multinational Multi-Role Tanker and Transport Fleet.

The Clingendael authors note that the insertion of the term specialization into the Strategic Compass was at the request of the Netherlands, based on the goals outlined in its Defense Vision 2035 from October of 2020, which states that, “each country has a natural leaning towards certain capabilities and type of deployment,” and that, “[the Netherlands] should make better use of that added value in order to jointly achieve more effects and raise the quality of our operations.” Essentially, by specializing in capability areas of strength—such as submarines or cyber defense—and abandoning efforts in areas of weakness in favor of pooled endeavors and greater reliance on partner nations, EU member states will be able to increase overall EU capabilities for deterrence and defense, while still maintaining reasonable individual defense spending levels.

As Zandee and Stoetman explain, such specialization is often associated with a surrender of national sovereignty or an unacceptable level of dependency on other nations, which historically have prevented more countries from pursuing this path. Furthermore, as was noted in a 2020 report for the European Union Institute for Security Studies, despite the fact that the EU and its member states have invested in a range of policy mechanisms designed to pull governments closer together on defense, “the reality today is that the ‘alphabet soup’ of EU security and defence – CSDP, PESCO, EDF, CARD, CDP, MPCC, NIPs, EPF, etc. – has not yet led to any tangible shift in the Union’s capability base or readiness for deployment.”

Therefore, what Zandee and Stoetman propose is that EU member states, instead of primarily focusing on bolstering the bureaucratic apparatus needed to support closer cooperation on defense, that states instead cooperate by focusing on their own “niche or specialized capabilities,” and relying on partners for those capabilities in which it does not excel. In doing so, such specialization, “can strengthen the collective capabilities of European countries by strengthening capabilities across the whole spectrum, contribute to better interoperability, and enhance mutual trust and confidence.”

While states may point to a number of risks inherent in specialization, which include diminished defense industrial capacities—and a resultant loss of jobs at the national level—and the risk that partners will not provide access to their capabilities in times of need, the benefits are easy to see, in that specialization enables countries to concentrate on areas in which they already possess a robust industrial base and expertise, allowing those states to make more efficient use of existing resources. Furthermore, specialization allows smaller states access to capabilities that they would otherwise be unable to afford.

For the Clingendael report, the authors provide a number of different ways that EU members can go about the process of specialization, first noting that as a result of historic or geographic factors, many countries possess certain military capabilities that other states lack. For instance, landlocked nations typically have little to no naval presence, while they generally invest more in their land and air forces. In terms of the Netherlands, it is their ocean-going submarines that are unique, providing the country with the ability to group with other nations that focus on frigates or destroyers in order to enhance the overall European defense capability base, or to group with other submarine-having countries to cooperate on maintenance and support efforts.

Specialization can also entail the pooling and sharing of capabilities wherein countries that do not possess a certain capability are given the opportunity to still make use of that capability through a shared pool of resources. Examples of such pooling and sharing formats include the Multi-Role Transport and Tanker fleet, listed above. Other elements include “smart defense”, as developed by NATO, which, “encourages members to work with others wherever possible; to set the right priorities at home and together in Brussels; and to encourage nations, especially the smaller nations, to specialize in what they do best.” The Clingendael authors argue that the essential difference between pooling and sharing, smart defense, and specialization is that while the first two entail some degree of reliance on partner nations, it is not as great as with full-on specialization.

Another phrase oft-synonymous with specialization is collective tasks, such as the NATO Baltic Air Policing mission, which the authors call a type of “organised non-specialisation” as the Baltic states decide not to have a robust fighter capability “by design” but instead receive that capability from other nations, though without offering their own areas of expertise in exchange. Finally, the authors discuss the concept of defense integration, such as the naval cooperation between Belgium and the Netherlands, wherein one side (the Netherlands) provides education, training, and maintenance facilities for both countries’ M-class frigates and the other (Belgium) provides the same for the two countries’ minehunting vessels.

Based on these existing models, the authors propose a framework for European defense specialization that leverages three specific forms of specialization: structured European capability groups; specialization in support functions; and traditional specialization. In terms of structured European capability groups, the authors look at existing multinational formations such as the UK-led Joint Expeditionary Force, which emerged out of the 2014 NATO Wales Summit.

Improving European Specialization in Defense

The 2014 Wales Summit Declaration was where Allies agreed to the NATO Framework Nations Concept whereby countries agreed to develop framework nations or smaller groupings of countries that would commit, “to working systematically together, deepening and intensifying their cooperation in the long term, to create, in various configurations, a number of multinational projects to address Alliance priority areas across a broad spectrum of capabilities.” However, for the Clingendael authors, the result of these groupings has been, “a patchwork of multinational formats, which lacks structure and cohesion,” raising the question of what can be done to arrive at a scenario wherein European countries organize their capabilities in a more coordinated manner. To that end, the authors propose that the geographic location of member states be taken into account when formulating such groupings; that such capability groups be considered more for collective defense than crisis management operations; and that the possession of already existing niche capabilities should be considered when proposing further specialization.

In that way, the authors propose that European nations follow a largely geography-based model for structuring future European capability groups, with the continent grouped into Northern Europe; Eastern Europe; Central Europe; and South-Eastern Europe, with other groupings created based on the needs and specific capabilities of contributing EU member states. For instance, the authors note how the UK-led Joint Expeditionary Force is already focused on Northern Europe in terms of its participating members and its exercises; therefore, it could be further developed into a capability group for Northern Europe and the Arctic, with Norway contributing its surface fleet and air-defense capabilities, and the UK and Netherlands providing first responder capabilities—primarily with those countries’ marines corps forces—to allies Finland and Sweden in the event of a potential Russian invasion of their territory.

In addition to such regional groupings, the authors also state that European nations can group together to work on areas of specific interest both inside and outside of Europe. For instance, they propose the formation of a Special Forces group, whereby contributing countries provide either commandos or specific enablers—such as transport aircraft, helicopters, and submarines—with the Composite Special Forces Command of Denmark and the Benelux countries providing a template for other European nations to join together their special forces capabilities with other participating countries. Furthermore, such functional groupings could be coupled together with regional capability groups depending on the goal. For instance, countries grouped together for logistical support will need to interface with regional capability groupings, such as the Joint Expeditionary Force, in order to ensure that those regional groupings are able to supply their troops in the event of a future conflict.

Indeed, support functions are another overarching area in which the Clingendael authors propose that European nations cooperate in order to achieve greater overall capabilities in defense, while still keeping costs in check. To that end, the authors propose binational or multinational specialization in education and training—which presupposes that countries operate the same equipment and that military operators speak the same language—and point to the Belgian-Dutch joint work on frigate and minehunter maintenance, with France an ideal future candidate to join the two neighbors in such an undertaking. Furthermore, in future endeavors, such as with the European Patrol Corvette project between Italy, France, Greece, and Spain, the authors propose that specialization in support functions should be a key part of planning in order to prevent duplication of those functions by the participants. Furthermore the German-French-Spanish Future Air Combat System (FCAS) can similarly benefit from the participating members specializing in support functions before the first plane ever rolls off an assembly line.

In terms of traditional specialization, which the report defines as when, “countries completely [abandon] a capability while specialising in another, based on a mutual arrangement with at least one other country,” the authors state that there are almost no examples of it happening, as while many states have given up capabilities unilaterally, they have often done so without coordination with others. The most radical example of traditional specialization would be a country with a limited coast abandoning its navy in order to fully specialize in land and air forces.

However, such overarching models of specialization do not tend to come to fruition, as they would render the state abandoning its capabilities unacceptably reliant on partners in the event of a future conflict. Instead, the authors argue that traditional specialization tends to be found at the level of specific service components such as artillery, air mobile forces, aircraft carriers, submarines, fighter aircraft, or space assets. To that end, the authors propose that the NATO Defense Planning Process (NDPP) and the EU’s Coordinated Annual Review on Defence (CARD) be restructured so that member states can better work together, making better use of countries’ preexisting specializations in order to expand the capacity for collective defense of the EU and NATO.

In that light, the authors propose a number of specialization options for countries that wish to focus on a given capability area. These include a focus on long-range missile systems versus the short range firepower of tanks and artillery; a focus on heavy-lift helicopters compared to a ground-based vehicle transport fleet; and blue-water naval assets such as carriers and frigates versus brown water assets such as patrol boats and diesel-electric submarines. By achieving traditional specialization in these individual service components, countries can acquire the hardware that they know how to use well, leaving types of equipment outside their traditional area of competence to other nations.

More specifically, in terms of the Netherlands, the authors outline a number of different specialization options that the country could pursue. For example, they propose that, in terms of structured capability groups, that the Netherlands engage with other JEF participants to explore pathways to strengthen the force by making it, “even more effectively structured, equipped, trained and adapted to the Northern European theatre as a structured European capability group for operations in the context of collective defence,” with the, “Dutch Marine Corps contribution”, needing to be strengthened based on measures announced in the Dutch Defence White Paper 2022.

When it comes to specializing in support functions, the Clingendael authors propose that as both Germany and the Netherlands already employ the German-Dutch Boxer Armoured Transport Vehicle, there is room for the two sides to come to a specialization in support functions, with Germany taking responsibility for repair and maintenance of the Boxer and the Netherlands committing to the support of the Chinook heavy-lift helicopters that Germany has recently committed to purchase, and which the Netherlands already operates.

Finally, in terms of traditional specialization at the level of individual service components, the authors propose that the Netherlands coordinate its future specialization with Belgium, so that if Belgium were to consider acquisition of land-based missile defense–for example for the defense of the Port of Antwerp against long-range precision-guided munitions—then Dutch Patriot missile batteries could be first shared between the two countries, and then later handed over to Belgium as Belgium specializes in protecting the harbors of both countries. In return, the Netherlands’ own sea-based missile defense systems could be used to protect further-flung Belgian interests, permitting Brussels to spend less on naval frigates equipped with exoatmospheric interceptors.

Concluding Thoughts

Russia’s war in Ukraine has had a profound impact on the European security landscape, upending decades of relative peace between Europe and Russia. Furthermore, the Russian invasion did not occur in a vacuum and was—if not caused by the poor overall state of European defensive capabilities—at least made more attractive by the fact that European nations seemingly have taken in a three decade-long, post-Cold War, peace dividend while Russia’s military spending increased markedly over the last decade or more. While some European nations, such as Germany, seem to be awakening from their long slumber, years of neglect towards European defensive capabilities has left EU member states in a precarious position for the coming decade.

Because of those past failures, merely committing to meet the spending targets outlined earlier this century will not be enough for European states to realize the types and quantities of equipment needed to deter and defend against an aggressive and revanchist Russia. Instead, what is required is a more radical commitment by states to embrace their existing areas of expertise, while relying on partners to provide the capabilities that they lack.

To overcome this, EU member states will have to: provide more resources to existing structured European capability groups like the UK-led Joint Expeditionary Force and create new regional and task-specific groupings; follow the Belgian-Dutch BeNeSam model by having countries specialize in the support of specific equipment and capabilities; and actively work to specialize in terms of individual weapons system by, for example, abandoning pursuit of sea-based missile defense in favor of shorter-range systems.

However, states will also have to reckon with the fact that in doing so, they will be surrendering at least some part of their national sovereignty in terms of defense. While such an abandonment of sovereignty will likely encounter stern political opposition in many states, if Europe truly wants to fulfill its pursuit of “European strategic autonomy,” individual EU member states must accept the fact that they cannot do it all themselves. Furthermore, they must also understand how their past efforts to collaborate have not done enough to realize the capabilities Europe needs for defense against a peer-competitor. Therefore, it is time for European states to choose to embrace defense specialization. If they do not, and Europe is left vulnerable to coercion or attack from Russia in the future, European Union member states will have no one to blame but themselves.